Talent hits a target no one else can hit. Genius hits a target no one else can see.

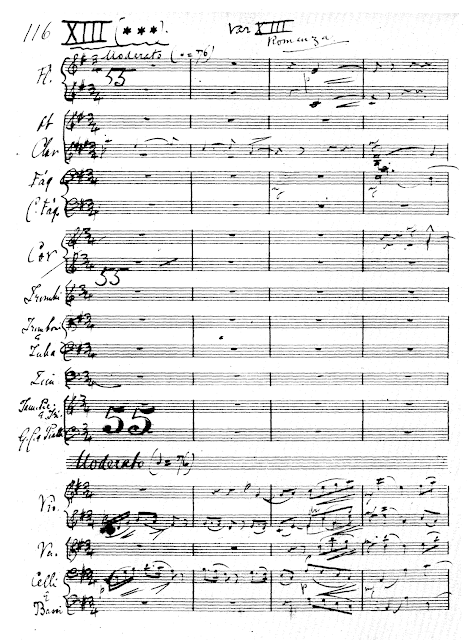

Edward Elgar cites a brief melodic fragment from Felix Mendelssohn’s concert overture Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage in Variation XIII of the Enigma Variations. Appearing in the full score enclosed by quotation marks, these fragments are performed by the first B-flat Clarinet in a span of 5.5 quarter beats dispersed over three measures. Elgar further elaborates these melodic snippets into a complete seven bar solo. The first two quotations are in A-flat major, and a third is in E-flat major. There is another Mendelssohn fragment in F minor performed by the trumpets and trombones, but it is not identified by quotation marks because it departs from the original major mode. In all, there are four Mendelssohn fragments with two in A-flat major, one in F minor, and the last in E-flat major.

The significance of the key letters from those Mendelssohn fragments — A, E, and F — is they are an anagram of a well-known musical cryptogram taken from the initials of the violinist Joseph Joachim’s romantic motto “Frei aber einsam” (Free but lonely). The presence of such a conspicuous musical cipher in the Mendelssohn fragments is extraordinary for two reasons. The first is that legacy scholars such as Julian Rushton failed to detect something so transparently concealed in plain sight. The second is that it forcefully suggests the existence of more cryptograms in Variation XIII, and by extension, the rest of the Enigma Variations.

The conventional wisdom stubbornly maintains that the Mendelssohn fragments are extraneous to the Enigma Variations. That opinion is superficially justified because these melodic extracts originate from an entirely different work. This is one instance in which the conventional wisdom has proven to be monumentally wrong. Far from being unrelated, the Mendelssohn fragments conceal a rich cache of cryptograms that confirm the identities of the covert melodic Theme and the secret friend memorialized in Variation XIII. This really should come as no surprise because Elgar was an expert cryptographer. The Mendelssohn fragments harbor or form a part of at least thirteen cryptograms:

- FAE Cipher

- FACE Cipher

- Mendelssohn E.F.B. Cipher

- AMF Cipher

- Mendelssohn Keynotes Cipher

- Mendelssohn Scale Degrees Cipher

- Dual Initials Enigma Cipher

- Romanza Cipher

- Mendelssohn Pi Cipher

- Mendelssohn Pi-C Cipher

- Dominant-Tonic-Dominant (5-1-5) Cipher

- Melodic Intervals Cipher

- See Abba Mendelssohn Cipher

Further research has unveiled two more cryptograms that may be added to the list, bringing the total of Mendelssohn fragments ciphers to fifteen. Before describing these two new cipher discoveries in detail, it is first necessary to briefly revisit the importance of two numbers granted a marked emphasis in numerous Enigma Variations ciphers. They are the numbers four and six.

The numbers four and six appear over and over again in multiple ciphers unearthed in the Enigma Variations. Sometimes these numbers appear separately and at other times in tandem. There are four string parts in the Enigma Locks Cipher located in the Enigma Theme’s openings six measures. A Music Box Cipher is also ensconced in those same six bars, and its decryption consists of four different languages whose first letters are an acrostic of Elgar. In a masterful stroke, Elgar expertly encoded his entire last name using a cipher cloaked within another. For anyone to suspect that such an extraordinary encryption could be the result of something as pernicious as confirmation bias or an overactive imagination would be tantamount to insisting that Winston Churchill was a teetotaler. It was Churchill who confided, “Always remember that I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me.”

The numbers four and six emerge time and time again in various Enigma Variations ciphers. There are four subtitles in the Frei Acrostic Anagram Cipher. Likewise, there are four Mendelssohn fragments in Variation XIII which hold numerous ciphers. The opus number (36) of the Enigma Variations is the product of six multiplied by itself, and there are six titles for various movements that are each six letters in length. Elgar’s peculiar emphasis on the numbers four and six in the Enigma Variations ciphers makes perfect sense when one recognizes that the covert Theme’s title originates from Psalm 46. The complete title of the unstated Principal Theme is six words in length: Ein feste Burg ist Unser Gott. There are 24 letters in that title, the sum of four sixes.

Mendelssohn Clarinet Solo Nominal Notes Cipher

Elgar’s coded emphasis on the numbers four and six throughout the Enigma Variations ciphers invites the application of those same integers to the notes of the B-flat clarinet solos in Variation XIII. These plaintive solo passages commence with the seemingly anomalous Mendelssohn fragments and have a total of ten notes. The first four notes complete the Mendelssohn quotation, and these are followed by six more notes that round out the solo. The emergence yet again of the numbers four and six in connection with the Mendelssohn fragments and their melodic elaboration is not a coincidence but represents a further coded emphasis on those two integers.

The B-flat clarinet is a transposing instrument that plays a written or nominal note one whole step lower as the concert or sounding pitch. The first two Clarinet solos sound in A-flat major but are written a whole step higher in the key of B-flat major. Counting forwards on the written part to the fourth note of the Mendelssohn quotation arrives on B-flat. The next or fifth note (F) is the first in Elgar’s melodic elaboration and is followed by the sixth note (E). The fourth through sixth notes of the first two written B-flat clarinet solos commencing with the Mendelssohn quotations are B-flat, F, and E. Those three letters are significant because they are the initials of the covert Theme in reverse.

One would never know to examine or sequester the fourth through sixth notes of the A-flat clarinet solos in Variation XIII written in B-flat unless the importance of the numbers four and six was first recognized. These numbers are subtly identified within each A-flat major clarinet solo as the initial four notes constitute the Mendelssohn quotation, and these are followed by six more to complete the passage. The cryptographic importance of those integers is further highlighted by their repeated appearance in numerous Enigma Variations ciphers.

Clarinet A Major Key Signature Transposition Cipher

It has been shown how Elgar cleverly encodes the initials (E. F. B.) for the covert Theme using the fourth through sixth notes of the A-flat major clarinet solos in Variation XIII that open with the Mendelssohn quotations. He also enciphers those same initials with the accidentals from the clarinet’s key signature. Variation XIII is set in G major, a key nominally written for the B-flat clarinet a whole step higher in A major. The key signature of A major has three sharps: F-sharp, C-sharp, and G-sharp. When played by the B-flat clarinet a major second downward, those three accidentals sound as E, B, and F-sharp. Those are the initials for Ein feste Burg. This clarinet key signature cipher reprises a similar encoding technique used in the Enigma Keys Cipher without the added step of transposition. With his use of musical transposition as a form of encipherment, Elgar covertly tips his hat to a whole class of transposition ciphers.

The initials for the hidden melody are encoded in at least a dozen ways throughout the Enigma Variations. It has just been revealed how the Mendelssohn Clarinet Solo Nominal Notes Cipher and Clarinet Key Signature Cipher both encode those initials. The Enigma Keys Cipher encodes them through the accidentals for the Enigma Theme's G minor (B-flat, E-flat) and G major (F-sharp) modes. The Nimrod Timpani Cipher does so with the tuning for the three timpani drums in Variation IX shown on the score as E-flat, B-flat, and F.

The FAE Mendelssohn Cipher in Variation XIII enciphers these initials based on the number of times a fragment is stated in a given key, then converts that number to the corresponding scale degree of that mode. The Letter Cluster Cipher is constructed from the letters from the titles of Variations XII (B. G. N.) and XIV (E. D. U., and Finale). The Enigma Date Cipher at the end of the original score provides those same initials as an abbreviation for February as “FEb.” The Dominant-Tonic-Dominant Cipher is embedded in the Mendelssohn fragments of Variation XIII and also ingeniously encodes these initials. The Cover Page Cipher is where Elgar traced a box and wrote the letters "FEb" twice on the original cover page of the Enigma Variations. The Enigma Variations Key Numbers Cipher also encodes the initials “E.F.B.” The tenth is the Mendelssohn Melodic Intervals Cipher. With so many ciphers pinpointing the same set of initials, is it absurd to maintain they must be coincidental or fabricated.

The interrelated decryptions of the Enigma Variations Ciphers are mutually consistent and reinforcing, erecting an elaborate yet rational set of solutions to one of musicology’s enduring mysteries. With so many ciphers pinpointing the same answers, there is no room left for doubt. The ciphers are genuine, and on that basis, we may be confident that the answers they encode are true and accurate. These solutions to Elgar’s enigmas are highly unpalatable to secular scholars like Julian Rushton who reflexively attribute them to coincidence, confirmation bias, and even contrivance. Ultimately the only thing that is contrived is Rushton's vacuous objections. Like the Bible they routinely disparage, academics contend the Enigma ciphers and their decryptions must all be concocted in some elaborate ruse to misinform and mislead rather than to enlighten and guide. If the ciphers are merely the product of an overactive or determined imagination, how then does one account for their precise and consistent solutions? The secret melody to the Enigma Variations is Ein feste Burg by Martin Luther. The secret friend of Variation XIII is Jesus Christ, Elgar’s inspiration behind not only the Enigma Variations but also to his sacred oratorios: The Light of Life (Lux Christi), The Dream of Gerontius, The Apostles, and The Kingdom. To learn more about the secrets of Elgar’s Enigma Variations and its manifold ciphers, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.