God writes the gospel, not in the Bible alone, but on trees and flowers and clouds and stars.

This is what I hear all day – the trees are singing my music – or have I sung theirs?

Music is written on the skies for you to note down.

Edward Elgar

Variation X is dedicated to Dora Penny (1874 – 1964), the daughter of Reverend Alfred Penny of Wolverhampton. Following the death of his first wife, Reverend Penny wed the sister of William Meath Baker, the variant portrayed in Variation IV. Elgar gave Dora the nickname “Dorabella” from Mozart’s opera Così fan tutte. She was a frequent travel companion when he went on outings such as kite flying or bicycle riding. Dora enjoyed dancing to his music, and her variation captures her graceful, delicate spirit. In a teasing way, it makes light of her stutter in the opening woodwind phrase that may be sung to her nickname (“Dor-a-bel-la”). The movement is given the subtitle Intermezzo, and it is one of the longest of the variations.

Dora made numerous attempts to guess the hidden melody, all to no avail. After speculating in vain on the hidden tune, she begged Elgar for the answer. He replied, “Oh, I shan’t tell you that, you must find it out for yourself.” “But I’ve thought and racked my brains over and over again,” she insisted. He answered, “Well, I’m surprised. I thought that you, of all people, would guess it.”[1] Significantly, he never cooled her quest for the hidden tune by suggesting that there was none to begin with, or that her movement was not a “variation” at all.

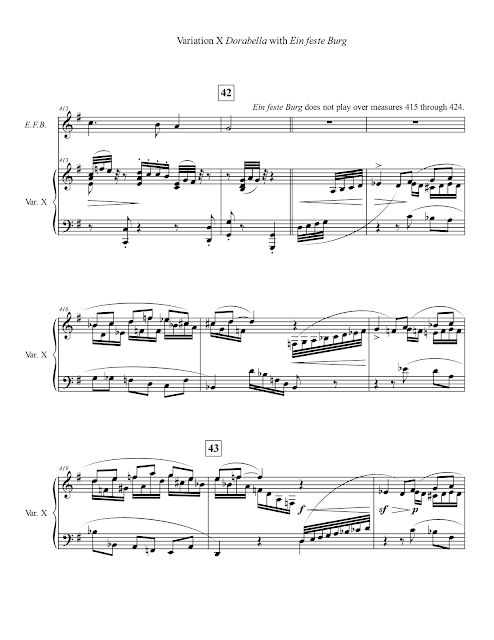

Contrary to the claims of prominent Elgar scholars, Dorabella is demonstrably a variation. Ein feste Burg plays through and over Variation X as shown in Figure 19.1.

Dora’s “Inner Voices”

In her memoir, Dora recalls that Elgar “. . . said there was only a trace of the ‘Enigma’ theme in the Intermezzo which no-one would be likely to find unless he knew where to look for it.”[2] Elgar gives a hint about where to look in explanatory notes written in 1927 for the Aeolian piano rolls. Concerning this variation, Elgar wrote the “inner sustained phrases at first on the viola and later on the flute should be noted.”[3] His brief remarks draw attention to the inner melody line, yet give no particular reason why. Following the discovery of the unstated principal Theme, the reason is perfectly clear: The first four notes of the concluding phrase of Ein feste Burg are quoted twice by the inner countermelody.The first four-note fragment of Ein feste Burg emerges at measure 408, and the second at measure 430. In the melodic mapping, the final cadence of Ein feste Burg is immediately followed in mid-measure by a double barline (see measures 414 and 436 in Figure 19.1), a feature that conveniently demarcates the ending of the covert Theme. No wonder Elgar told Dora that of all people she would be the one to correctly guess the melodic solution. Out of all the variations, Dorabella directly quotes the first four notes of Ein feste Burg’s ending phrase, expertly camouflaged in an augmented form by the inner voice. This is not the only time Elgar slips in the final phrase of Ein feste Burg, for he quotes it masked in a dotted rhythmic pattern at Rehearsal 66 in the Finale. While everyone searched in vain for the beginning of the hidden melody, Elgar playfully flaunts its final phrase out in the open, thinly disguised by rhythmic alterations.

In her memoir, Dora Powell recounts a visit to Craig Lea when Elgar was scouring various English translations of the Bible to assemble a suitable libretto for The Apostles. As he struggled to find just the right line to follow one of Christ’s Beatitudes, he asked Dora for her recommendation. She suggested a quotation from Psalm 85:

The study seemed to be full of Bibles. He had a Bible open on the table in front of him and there seemed to be a Bible on every chair and even one on the floor.“Goodness!” I said. “What a collection of Bibles! What have you got there besides the Authorized and Revised Versions?”“I don't know; They've been lent to me. I say, d’you know that the Bible is a most wonderfully interesting book?“Yes,” I said, “I know it is.”“What do you know about it? Oh I forgot. Perhaps you do know something about it? Anyway, I've been reading a lot of it lately and have been quite absorbed.”He appeared to be looking out texts and I offered to help.“I want something that will fit in here”—pointing to a line [where Christ sang “Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness for they shall be filled.”]I thought for a moment and fortunately something suitable occurred to me and I quoted it. [“Mercy and truth are met together: righteousness and peace have kissed each other.”]“You don’t mean to tell me that comes in the Bible? Show it to me.”I found the eighty-fifth Psalm in one of the Bibles and laid it before him.“Well! That is extraordinary! It’s just what I want here.”

Dora’s familiarity with the Psalms justifies why Elgar conceded that she would be the one to correctly guess the melodic solution to the Enigma Theme. Contrary to his revealing concession, Elgar stipulates in the original 1899 program note that the solution to his Enigma “. . . must be left unguessed.” The solution was so beyond the bounds of possibility for a Roman Catholic composer that no one, not even Dora, would ever guess the battle hymn of the Reformation.

As the daughter of an Anglican Rector and missionary, Dora was exceedingly familiar with the standard Anglican hymnal. In that context, her life experience enjoyed a very close connection to the hidden theme. On page 324 of A Dictionary of Hymnology published in 1892, it states Ein feste Burg “. . . has now become well-known in England, and in its proper form is included in the C. B. for England, 1863.” “C. B.” is an abbreviation for Chorale Book. Elgar said the missing melody was “. . . so well known that it is extraordinary that no one has spotted it yet.” Did he read the Dictionary of Hymnology? Among Elgar’s friends when he composed the Enigma Variations, Dora was the most active musically. In her own words she explains, “I was so mixed up with tunes in those days; Choral music; Church music, and orchestral music — and then my own solo singing, scenes from opera, songs, ballads, and so on.”[4]

Choral music, church music, and orchestral music – what popular tune could be featured so prominently in all three genres? The only credible answer is Ein feste Burg. Not only was it a standard in Anglican hymnals, but it also became very popular during the Bach resurgence in England beginning in the 1870s because Bach’s most famous cantata (BWV 80) is a series of variations based on that renowned theme. In opera, Ein feste Burg is well known because it is featured in Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots, the most successful opera of the nineteenth century. In orchestral music, it is quoted in numerous works by no less than J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Schumann, Nicolai, Raff, Wagner, Liszt, and Reinecke. No other melody is featured so prominently, frequently, or famously by the great German masters. As late as March 1853, Robert Schumann (Elgar’s “ideal”) planned to compose a sacred oratorio about Martin Luther featuring Ein feste Burg in the final climactic chorus.[5] If Ein feste Burg was profound enough to attract the attention of some of the greatest composers of the German school — particularly those Elgar venerated and emulated — then the magnetic allure of this powerful hymn could not have escaped Elgar's respect and artistic admiration.

In the Royal life of England, Ein feste Burg was given a prominent place of honor as shown by the coronations of 1902 and 1911, global events in an Edwardian era attended by leaders and representatives from around the world when the sun did not set on the British Empire. At the 1902 coronation of King Edward VII, Ein feste Burg was performed multiple times, first as a hymn during the processional, and later in Wagner’s Kaisermarsch.[6] This same hymn was performed at the 1911 coronation of King George V and Queen Mary, again as part of the processional music and also in the homage anthem composed by Sir Frederick Bridge “. . . making liberal use of Ein’ feste Burg.”[7] Elgar certainly heard if not performed Ein fest burg on numerous occasions in the years preceding the genesis of his Enigma Variations because of the Bach resurgence that swept England beginning in the 1870s. Bach’s works were routinely performed at the Three Choirs Festival beginning in the early 1870s. In 1871 the St. Matthew’s Passion was first performed there, and Bach’s and Mendelssohn’s music was commonplace in England throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Elgar began playing violin with the Festival orchestra in 1878. The Monthly Musical Record confirmed Bach’s Cantata A Stronghold Sure (Ein Feste Burg) was performed at the Three Choirs Festival on September 10, 1890.

Prominent Elgar scholars have made little headway in drawing any substantive connection between Dorabella and the Enigma Theme. Some even go so far as to insist Dorabella is not a variation at all. For example, Julian Rushton flatly declares “‘Dorabella’ is no variation . . .”[8] Such a claim begs the question of why Elgar used the word “Variation” in connection with this movement. The only obvious explanation is Dorabella is precisely what Elgar called it – a variation. When scholars sharpen their sensibilities to the slightest subtly, they risk dulling their minds to the agonizingly obvious. Elgar scholarship, like all other disciplines, suffers from more than one example of this disorder. Indeed, Rushton’s blunder is far from being the lone exception. To his credit, Rushton's claim is accurate regarding 33 out of 74 measures, or 45% of the work. Nonetheless, such a percentage falls short of a passing grade.

Melodic Interval MirroringFigure 19.2 illustrates precisely how Ein feste Burg was carefully mapped over Variation V based on melodic interval mirroring and the principles of counterpoint. Melodic interval mirroring occurs when note intervals from Ein feste Burg are reflected in the variation over comparable or identical distances between notes. These notes do not necessarily appear in the melody line of the variation. The contrapuntal devices of similar and contrary motion were also considered in this analysis. Similar motion is when both voices move in the same direction, but not necessarily by the same degree. Contrary motion takes place when Ein feste Burg moves in the opposite direction than the variation, again not necessarily by the same interval. Similar motion is indicated by SM, and contrary motion by CM. For the purposes of this analysis, similar motion includes any instances of parallel motion, and contrary motion any instances of oblique motion. In some cases, the upper voice of the variation moves parallel with Ein feste Burg while the bass line moves in a contrary manner. An effective counterpoint typically employs a fairly balanced mix of contrary and similar motion, something clearly evident with this mapping.

In Figure 19.2 a melodic conjunction is represented by a diamond-shaped note head, and a harmonic conjunction by a triangle-shaped note head. A melodic conjunction is defined as any matching melody note between Ein feste Burg and the movement's melody line. A harmonic conjunction is defined as a match between a melody note from the covert principal Theme and any non-melodic note from the movement. Both melodic and harmonic conjunctions must sound together to be considered a match.Table 19.1 identifies 104 melodic conjunctions between Ein feste Burg and Variation X. A melodic conjunction is defined as any simultaneously shared note between both melody lines. Based on this analysis, it was determined Ein feste Burg does not play over 33 measures of the variation:

Dora’s “Inner Voices”

In her memoir, Dora recalls that Elgar “. . . said there was only a trace of the ‘Enigma’ theme in the Intermezzo which no-one would be likely to find unless he knew where to look for it.”[2] Elgar gives a hint about where to look in explanatory notes written in 1927 for the Aeolian piano rolls. Concerning this variation, Elgar wrote the “inner sustained phrases at first on the viola and later on the flute should be noted.”[3] His brief remarks draw attention to the inner melody line, yet give no particular reason why. Following the discovery of the unstated principal Theme, the reason is perfectly clear: The first four notes of the concluding phrase of Ein feste Burg are quoted twice by the inner countermelody.

The first four-note fragment of Ein feste Burg emerges at measure 408, and the second at measure 430. In the melodic mapping, the final cadence of Ein feste Burg is immediately followed in mid-measure by a double barline (see measures 414 and 436 in Figure 19.1), a feature that conveniently demarcates the ending of the covert Theme. No wonder Elgar told Dora that of all people she would be the one to correctly guess the melodic solution. Out of all the variations, Dorabella directly quotes the first four notes of Ein feste Burg’s ending phrase, expertly camouflaged in an augmented form by the inner voice. This is not the only time Elgar slips in the final phrase of Ein feste Burg, for he quotes it masked in a dotted rhythmic pattern at Rehearsal 66 in the Finale. While everyone searched in vain for the beginning of the hidden melody, Elgar playfully flaunts its final phrase out in the open, thinly disguised by rhythmic alterations.

In her memoir, Dora Powell recounts a visit to Craig Lea when Elgar was scouring various English translations of the Bible to assemble a suitable libretto for The Apostles. As he struggled to find just the right line to follow one of Christ’s Beatitudes, he asked Dora for her recommendation. She suggested a quotation from Psalm 85:

The study seemed to be full of Bibles. He had a Bible open on the table in front of him and there seemed to be a Bible on every chair and even one on the floor.“Goodness!” I said. “What a collection of Bibles! What have you got there besides the Authorized and Revised Versions?”“I don't know; They've been lent to me. I say, d’you know that the Bible is a most wonderfully interesting book?“Yes,” I said, “I know it is.”“What do you know about it? Oh I forgot. Perhaps you do know something about it? Anyway, I've been reading a lot of it lately and have been quite absorbed.”He appeared to be looking out texts and I offered to help.“I want something that will fit in here”—pointing to a line [where Christ sang “Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness for they shall be filled.”]I thought for a moment and fortunately something suitable occurred to me and I quoted it. [“Mercy and truth are met together: righteousness and peace have kissed each other.”]“You don’t mean to tell me that comes in the Bible? Show it to me.”I found the eighty-fifth Psalm in one of the Bibles and laid it before him.“Well! That is extraordinary! It’s just what I want here.”

Dora’s familiarity with the Psalms justifies why Elgar conceded that she would be the one to correctly guess the melodic solution to the Enigma Theme. Contrary to his revealing concession, Elgar stipulates in the original 1899 program note that the solution to his Enigma “. . . must be left unguessed.” The solution was so beyond the bounds of possibility for a Roman Catholic composer that no one, not even Dora, would ever guess the battle hymn of the Reformation.

As the daughter of an Anglican Rector and missionary, Dora was exceedingly familiar with the standard Anglican hymnal. In that context, her life experience enjoyed a very close connection to the hidden theme. On page 324 of A Dictionary of Hymnology published in 1892, it states Ein feste Burg “. . . has now become well-known in England, and in its proper form is included in the C. B. for England, 1863.” “C. B.” is an abbreviation for Chorale Book. Elgar said the missing melody was “. . . so well known that it is extraordinary that no one has spotted it yet.” Did he read the Dictionary of Hymnology? Among Elgar’s friends when he composed the Enigma Variations, Dora was the most active musically. In her own words she explains, “I was so mixed up with tunes in those days; Choral music; Church music, and orchestral music — and then my own solo singing, scenes from opera, songs, ballads, and so on.”[4]

Choral music, church music, and orchestral music – what popular tune could be featured so prominently in all three genres? The only credible answer is Ein feste Burg. Not only was it a standard in Anglican hymnals, but it also became very popular during the Bach resurgence in England beginning in the 1870s because Bach’s most famous cantata (BWV 80) is a series of variations based on that renowned theme. In opera, Ein feste Burg is well known because it is featured in Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots, the most successful opera of the nineteenth century. In orchestral music, it is quoted in numerous works by no less than J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Schumann, Nicolai, Raff, Wagner, Liszt, and Reinecke. No other melody is featured so prominently, frequently, or famously by the great German masters. As late as March 1853, Robert Schumann (Elgar’s “ideal”) planned to compose a sacred oratorio about Martin Luther featuring Ein feste Burg in the final climactic chorus.[5] If Ein feste Burg was profound enough to attract the attention of some of the greatest composers of the German school — particularly those Elgar venerated and emulated — then the magnetic allure of this powerful hymn could not have escaped Elgar's respect and artistic admiration.

In the Royal life of England, Ein feste Burg was given a prominent place of honor as shown by the coronations of 1902 and 1911, global events in an Edwardian era attended by leaders and representatives from around the world when the sun did not set on the British Empire. At the 1902 coronation of King Edward VII, Ein feste Burg was performed multiple times, first as a hymn during the processional, and later in Wagner’s Kaisermarsch.[6] This same hymn was performed at the 1911 coronation of King George V and Queen Mary, again as part of the processional music and also in the homage anthem composed by Sir Frederick Bridge “. . . making liberal use of Ein’ feste Burg.”[7] Elgar certainly heard if not performed Ein fest burg on numerous occasions in the years preceding the genesis of his Enigma Variations because of the Bach resurgence that swept England beginning in the 1870s. Bach’s works were routinely performed at the Three Choirs Festival beginning in the early 1870s. In 1871 the St. Matthew’s Passion was first performed there, and Bach’s and Mendelssohn’s music was commonplace in England throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Elgar began playing violin with the Festival orchestra in 1878. The Monthly Musical Record confirmed Bach’s Cantata A Stronghold Sure (Ein Feste Burg) was performed at the Three Choirs Festival on September 10, 1890.

Prominent Elgar scholars have made little headway in drawing any substantive connection between Dorabella and the Enigma Theme. Some even go so far as to insist Dorabella is not a variation at all. For example, Julian Rushton flatly declares “‘Dorabella’ is no variation . . .”[8] Such a claim begs the question of why Elgar used the word “Variation” in connection with this movement. The only obvious explanation is Dorabella is precisely what Elgar called it – a variation. When scholars sharpen their sensibilities to the slightest subtly, they risk dulling their minds to the agonizingly obvious. Elgar scholarship, like all other disciplines, suffers from more than one example of this disorder. Indeed, Rushton’s blunder is far from being the lone exception. To his credit, Rushton's claim is accurate regarding 33 out of 74 measures, or 45% of the work. Nonetheless, such a percentage falls short of a passing grade.

Melodic Interval Mirroring

Figure 19.2 illustrates precisely how Ein feste Burg was carefully mapped over Variation V based on melodic interval mirroring and the principles of counterpoint. Melodic interval mirroring occurs when note intervals from Ein feste Burg are reflected in the variation over comparable or identical distances between notes. These notes do not necessarily appear in the melody line of the variation. The contrapuntal devices of similar and contrary motion were also considered in this analysis. Similar motion is when both voices move in the same direction, but not necessarily by the same degree. Contrary motion takes place when Ein feste Burg moves in the opposite direction than the variation, again not necessarily by the same interval. Similar motion is indicated by SM, and contrary motion by CM. For the purposes of this analysis, similar motion includes any instances of parallel motion, and contrary motion any instances of oblique motion. In some cases, the upper voice of the variation moves parallel with Ein feste Burg while the bass line moves in a contrary manner. An effective counterpoint typically employs a fairly balanced mix of contrary and similar motion, something clearly evident with this mapping.

In Figure 19.2 a melodic conjunction is represented by a diamond-shaped note head, and a harmonic conjunction by a triangle-shaped note head. A melodic conjunction is defined as any matching melody note between Ein feste Burg and the movement's melody line. A harmonic conjunction is defined as a match between a melody note from the covert principal Theme and any non-melodic note from the movement. Both melodic and harmonic conjunctions must sound together to be considered a match.

Table 19.1 identifies 104 melodic conjunctions between Ein feste Burg and Variation X. A melodic conjunction is defined as any simultaneously shared note between both melody lines. Based on this analysis, it was determined Ein feste Burg does not play over 33 measures of the variation:

- Measure 385

- Measures 397 to 404

- Measures 415 to 424

- Measures 437 to 450

Measures over which the unstated principal Theme does not play are defined as inactive. Alternatively, measures over which Ein feste Burg plays are defined as active. Based on this analysis, melodic conjunctions are dispersed over 35 out of 41 active measures, or 55% of the movement, and 85% of all active measures. Unlike other variations in which the percentage of active measures is substantially higher, Variation X has a much lower percentage. This is likely the case because Elgar drew on earlier material from his sketchbooks for this movement that was not expressly composed as a counterpoint to Ein feste Burg. Based on his surviving sketchbooks, it is obvious Elgar exercised a lifelong habit of copying and revising musical ideas.[9] The strongest case for just such an approach may be made regarding Variation X, particularly since Elgar carefully cordons off this earlier material with double barlines as observed in measures 414 and 436.

Table 19.2 breaks down melodic conjunctions between Ein feste Burg and Variation X according to note type, frequency, and percentage. There are seven shared melody note types with frequencies ranging from a low of 3 (C-sharp) to a high of 28 (G).

Table 19.3 provides a breakdown of all shared notes between Ein feste Burg and Variation X. There are 172 shared notes dispersed over 41 active measures. As was previously observed, 33 measures were deemed inactive because Ein feste Burg does not play over them. Hence almost 98% of all active measures contain sequentially shared notes with the unstated principal Theme. There are 104 melodic notes and 68 chordal notes from Variation X that are shared with Ein feste Burg. There are 8 shared note types with frequencies ranging from a low of 3 (E-sharp) to a high of 43 (G).

Table 19.4 summarizes all note conjunctions between Ein feste Burg and Variation X based on the mapping outlined in Figure 15.1. Totals and percentages for each note type are shown for both the melodic and chordal categories. 60% of note conjunctions are melodic, and 40% are chordal. Considering the relative scarcity of notes in the bass line, it is reasonable to anticipate that the majority of note conjunctions would occur in the upper voices.

Conclusion

The preponderance of the evidence presented in the above Figures and Tables demonstrates that Variation X is a clear and convincing counterpoint to Ein feste Burg. To learn more about the secrets behind the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar's Enigmas Exposed. Please support my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

Conclusion

The preponderance of the evidence presented in the above Figures and Tables demonstrates that Variation X is a clear and convincing counterpoint to Ein feste Burg. To learn more about the secrets behind the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar's Enigmas Exposed. Please support my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

[1] Powell, D. M. (1947). Edward Elgar: Memories of a variation (2nd ed.). London: Oxford University Press, p. 23.

[2] Ibid, p. 15.

[3] Elgar, Edward. My Friends Pictured Within. The Subjects of the Enigma Variations as Portrayed in Contemporary Photographs and Elgar’s Manuscript (Sevenoaks: Novello, n.d. [1946], republication of notes for Aeolian Company’s piano rolls, 1929)

[4] Turner, Patrick. Elgar’s Enigma Variations: A Centenary Celebration (Thames Publishing, London, 2007), 112.

[5] Patterson, A. W. (1908). Schumann. New York & London: J.M. Dent & Co. and E.P. Dutton and Co. (Original work published 1903), p. 83.

[6] The Musical Times, September 1, 1902, p. 577-578

[7] Richards, Jeffrey (2001). Imperialism and music: Britain, 1876-1953. Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 108-109.

[8] Rushton, Julian. Elgar: Enigma Variations (Cambridge Music Handbooks). New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 47.

[9] The Cambridge Companion to Elgar (Cambridge Companions to Music). (2005). New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 39.

No comments:

Post a Comment