Cast thy bread upon the waters: for thou shalt find it after many days.

A decade has come and gone since the launch of this blog which plumbs the depths of Edward Elgar’s symphonic masterpiece, the Enigma Variations. During that period, 130 posts received more than 405,000 pageviews from a global audience. My discoveries have also been featured in various magazines, newspapers and radio programs. After nine excruciating years of hemming and hawing by its editors, Wikipedia reluctantly lifted its embargo by finally citing my research in their article about the Enigma Variations. I may not have arrived yet, but I have most definitely departed. In a long overdue retrospective, the dawn of this blog’s tenth anniversary heralds an auspicious moment to look back at how it all began.

It was late October 2006 when I performed the Enigma Variations as a sectional violinist with the Bohemian Club Symphony Orchestra in San Francisco under the capable baton of Richard Williams. Maestro Williams exhibited a conspicuous zeal for Elgar's music, devoting time at rehearsals to talk about the underlying mysteries concerning a hidden principal Theme, a “dark saying” ensconced within the Enigma Theme, and a secret friend memorialized in Variation XIII. My curiosity was soon set ablaze by his incandescent exegeses. It was then and there that I decided to seek out the answers to these tantalizing riddles. My wife purchased a raft of used library books about Elgar to jumpstart my investigation, and I added further articles and works on the Enigma Variations to my burgeoning collection. My plan was to scour the literature for the answers which I had hoped were unearthed by my older and wiser forebears. Unfortunately, the more I read, the more it became excruciatingly evident that not a single soul had ever managed to crack Elgar's melodic strongbox. In the absence of credible and satisfying answers, I boldly decided to take a crack at it in a quest to unmask the answers for myself and posterity.

My nascent efforts to untangle Elgar’s contrapuntal Gordian Knot had me tied up in knots. Like all of my predecessors, my attempts at finding a convincing melodic solution proved fruitless and futile. I had eyes but could not see, ears but could not hear. Desperation moved me to appeal to the unmoved mover of my Christian faith. My predicament was reminiscent of the prophet Daniel when he and his fellow sages of ancient Babylon were challenged to interpret King Nebuchadnezzar’s disturbing yet hidden dream. Like the great king's dream, Elgar's absent principal Theme was a closely guarded secret. I invoked divine assistance to grant me the wisdom to see and hear what my more capable peers and predecessors failed to detect or comprehend. My personal experience confirmed that God answers prayer, and so I prayed for a miracle—the answers to Elgar's Enigma Variations.

Persistent prayer and study paved the way for my very own Enigma Day on February 3, 2009. It was a quiet Tuesday morning when I first hit upon an unexpected solution for the hidden melody that serves as a counterpoint to the Enigma Theme. That mystery tune is the Reformation hymn Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by Martin Luther, an epic theme quoted in the works of great German composers admired by Elgar like Bach, Mendelssohn, and Wagner. This was a startling discovery as Elgar was raised a devout Roman Catholic, and Luther was a controversial Roman Catholic priest and professor ignominiously excommunicated by Pope Leo X for heresy. The date of my melodic epiphany was remarkable because it coincided with the bicentennial of Felix Mendelssohn’s birth. What made the timing even more extraordinary was the Mendelssohn fragments which Elgar conspicuously sprinkled in Variation XIII served as the providential bread crumbs that led me through a deep dark forest to this breakthrough that nobody would ever guess.

My pièce de résistance was a contrapuntal mapping of Bach’s adaption of Ein feste Burg “through and over” the Enigma Theme. This melodic melding illustrated in vivid detail how those two dissimilar themes shared a remarkable horizontal congruence spanning 17 measures. This was a stunning find as Roger Fiske remarked “. . . how very hard it is to find anything that will go with Elgar’s theme even badly . . .” Up until that momentous moment, no other melody had ever been shown to attain an exact lengthwise fit with the Enigma Theme starting from its beginning on the second beat of measure 1 through the terminus of measure 17. Apart from a smattering of inconsequential accommodations for the Enigma Theme’s repeated modulations between G major and minor — a modal camouflage — no rhythmic alterations to Bach’s version of Ein feste Burg were required to produce this unprecedented fusion. The conflux between the Enigma Theme and Ein feste Burg persuaded me I had discovered the covert melody.

My preliminary findings were hurriedly prepared in a brief inaugural post which would later be removed after I contemplated writing a formal paper followed by a book. Prospective publishers admonished me not to release material on my blog if I wanted it to be seriously considered for publication. This resulted in a blackout on further disclosures until September 2010 when it became all too apparent that journals and academic publishers had no appetite for this admittedly esoteric subject. In my moment of triumph, I emailed invitations to top Elgar scholars like Julian Rushton and Clive McClelland to consult my introductory post and offer up their hearty approbations. With bated breath, I waited to be feted as a classical Sherlock Holmes for solving one of the most confounding riddles in music history. I did not have to wait long for my lofty hopes and aspirations to be dashed in a deluge of doubt and dismissive denunciations.

Rushton was the first to reply. He warned that I must be mistaken because Elgar was a Roman Catholic who would never contemplate quoting the music of heretical Lutheran. Such an objection cannot be taken seriously because it is in open conflict with Elgar’s decision to cite Mendelssohn’s music in Variation XIII. Rushton surely knows that Mendelssohn was baptized a Lutheran and remained a devout protestant throughout his adult life, even going so far as to compose the Reformation Symphony in honor of the 300th anniversary of the Augsburg Confession. By quoting Mendelssohn’s oeuvre, Elgar openly demonstrated a willingness to cite the music of a Lutheran. The presumption that Elgar’s faith precluded him from considering a protestant melody — particularly at a time when he was contemplating a symphony in honor of the high Anglican General Gordon — is the counterargument of an ignoramus or a fabulist. This melodic melee proved to be the opening salvo in a protracted tête-à-tête with Dr. Rushton whose alleged expertise in this arena proved far too often to be rooted in mythical fallacies rather than objective facts.

To his credit, Rushton did raise a more substantial objection by honing in some inscrutable dissonances in my contrapuntal mapping of Bach’s adaption of Ein feste Burg “through and over” the Enigma Theme. McClelland also echoed this justifiable grievance. While noting that Ein feste Burg presented a perfect horizontal fit with the Enigma Theme, Rushton and McClelland remained dubious because of the absence of a credible vertical alignment devoid of distasteful dissonances. In consideration of this reasonable objection and their sterling reputations, I went back to the drawing board and briefly dabbled with Mendelssohn’s Wedding March as a possible alternative. As born out by his sketchbooks, the lover’s theme from Elgar’s overture Cockaigne Op. 40 is indeed a counterpoint to Mendelssohn’s Wedding March, something I was blissfully unaware of when I fleetingly considered it as a prospective missing theme to the Enigma Variations.

The more I scrutinized my mapping of Mendelssohn’s Wedding March over the Enigma Theme, however, the more dissatisfying it became a viable solution. I soon returned again to my original thesis primarily because of the uncanny horizontal fit between Ein feste Burg and the Enigma Theme. Elgar’s standard reply to enigma solutions invokes the fundamental idea of a fit between the two melodies:

No: nothing like it.

I do not see the tune you suggest fits in the least.

E.E.

Merriam-Webster defines fit as “to be suitable for or to harmonize with,” and “to conform correctly to the shape or size of.” Elgar’s language is unambiguous, denoting definitively that both themes must be the same length. The first media report regarding my discovery surfaced within a month of my exhilarating announcement. It was published online in March 2009 by Tim Smith, the fine arts critic for The Baltimore Sun. Now I felt confident no other aspirant would dare assume credit for my discovery. All the glory ultimately belongs to my Heavenly Father for permitting me to assemble the pieces from this exquisitely elaborate puzzle.

Before I could venture beyond my preliminary findings, I suddenly and unexpectedly lost my job as a benefits analyst at Genworth Financial in late March 2009. As the sole provider for my wife and five children, this was a devastating blow that coincided with the height of the last financial crisis. Shortly before my abrupt departure, a humble coworker and devout follower of Jesus named Lois Hampton prophesied that one day I would be recognized for my musical discoveries and deliver lectures before rapt audiences. In that dark hour, I took comfort in Lois’ prophetic pronouncements knowing that all things work together for good for those who love God and live according to his purpose. I may have lost my job, but I had not lost hope or purpose because I still believed God had brilliant plans for my family and me.

I scrambled to make ends meet as a violin and viola instructor, but the flagging California economy and fading string programs in the public schools were grim harbingers. I enjoyed teaching at a local private music school in Cotati called Music To My Ears, but there were insufficient students to justify remaining in Northern California. When one of my violin students remarked rather despondently that the orchestra program at her high school was being shuttered, I could see the writing on the wall. It was time to leave for greener pastures. This was no longer the California I grew up in when orchestra programs flourished in elementary, middle and high schools. Plagued by natural and economic drought, California went from being the “breadbasket of the world” to the economic “basket-case” of America. The strings programs had to go, and consequently so did I and my family along with an exodus of countless other economic refugees that continues unabated to this day.

Donald, my twin brother who resides in Plano, urged me to consider relocating to the great state of Texas because of the vibrant strings programs in the public schools. I flew out that July to reconnoiter the market and decided it was worth the risk. I cashed in my modest retirement account with Genworth Financial accumulated over my four-year tenure to finance the biggest move of my life. When I told my father, Wayne, about my plans to move to Texas, he congratulated me and added with a wry grin, “You’re getting out just in time.” Over two long hot days that August, I made the drive to Texas in my 2002 model Toyota Corolla. My wife and children followed in September in our spacious Ford Chateau van nicknamed “El Presidente” towing a small U-Haul trailer packed to the hilt. The drive was unpleasantly sweltering because the van lacked a functioning air conditioner, and during the journey one of the rear tires picked up a nail that caused it to continually bleed off air pressure and require regular inflating.

As I plotted my escape from the People’s Republic of California, my blog attracted the attention of Richard Santa, a retired engineer. He made the remarkable discovery that Elgar encoded the mathematical constant Pi in the Enigma Theme’s opening measure. Santa sent me an early draft of his paper which would later appear in the journal Current Musicology published by Columbia University. My personal history includes a brief foray at Columbia University during the summer of 1986 where I attended the American Federation of Musicians' 28th Annual Congress of Strings under Music Director Joseph Silverstein and conductor Brian Salesky. The primary significance of Santa’s insight is that it eventually made me realize the Enigma Variations very likely harbored other cryptograms, a subject that I only vaguely understood or appreciated in those early days of discovery.

Within five months, my melodic solution was casually mentioned in the July 2009 issue of The Elgar Society Journal. At the bottom of page 50, Clive McClelland cites Ein feste Burg as a comparatively recent example of a melodic solution to the Enigma Variations that shares the “right length” with the Enigma Theme. Even McClelland recognized the unusual fit between the rhythmically intact forms of Ein feste Burg and the Enigma Theme, although he too balked at some “howling dissonances” that rendered the mapping untenable. I only recently stumbled upon this reference in January 2019 as I was perusing the archives of The Elgar Society Journal.

Shortly after I arrived in Texas in August 2009, McClelland emailed me a copy of his informative paper “Shadows of the Evening: New light on Elgar’s ‘Dark Saying’” which first appeared in the 2007 Winter issue of The Musical Times. As I pressed my case with him through repeated email exchanges, he impatiently threw down the gauntlet by demanding I prove the efficacy of my melodic solution by mapping it over any one of the other movements from the Enigma Variations. McClelland taunted that if I attempted such a project, I would soon be forced to abandon my theory. He based his bold challenge on the original 1899 program note where Elgar states, “. . . through and over the whole set [of Variations] another and larger theme ‘goes’ but is not played . . .” I accepted his challenge, selecting the most popular of the Variations (Nimrod) as the test subject for this contrapuntal tribunal. Through an innovative process known as melodic interval mapping, I sequentially matched notes from Ein feste Burg to Nimrod’s melody and harmony notes to realize a credible counterpoint. That exercise convinced me I had indeed hit on the right solution, and that I should pursue similar mappings for the remaining movements. During the Winter break in late 2009 through early 2010, I locked myself in a room and devoted every waking moment to this extended contrapuntal enterprise.

I prepared an audiovisual demonstration of my melodic mapping of Ein feste Burg “through and over” Nimrod, and published it on YouTube. McClelland and Rushton remained unswayed. A far more favorable impression was conveyed by the founder of the American Elgar Foundation, Richard Winter-Stanbridge. He telephoned me out of the blue to congratulate me on my discovery, exclaiming in our first conversation in September 2009 that my mapping of Ein feste Burg over Nimrod was as “clear as a pikestaff.” At that time, Richard was planning a movie to commemorate Elgar’s 150th birthday for which he prepared a short trailer. He invited me to be interviewed for this project with the intention of sharing my melodic solution to the Enigma Variations with a broader audience. The movie never materialized, but Richard’s unexpected call and words of encouragement were perfectly timed to spur me on in my budding enterprise. Little did I realize then that I had barely begun to scratch the surface of the many secrets expertly interwoven into the rich tapestry of the Enigma Variations.

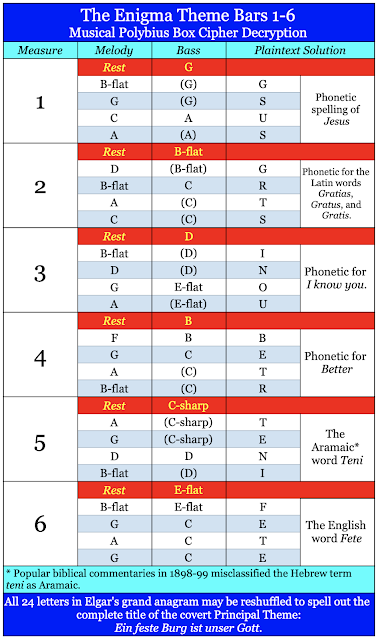

After completing my mappings of Ein feste Burg over each of the Variations, I began connecting key insights that pointed to the presence of a music cryptogram in the opening six measures of the Enigma Theme. The first and earliest was Santa’s discovery that Elgar encoded the mathematical ratio Pi in the first bar relying on the melodic scale degrees. This refuted the presumption there were no cryptograms in the Enigma Variations, a position espoused by Dr. Rushton who considers any “precompositional calculation unlikely.” The second was raised in Dr. McClelland’s paper where he perceptively surmised:

Elgar’s six-bar phrase is achieved by the characteristic four-note grouping, repeated six times with its reversible rhythm of two quavers and two crotchets. This strongly suggests the cryptological technique of disguising word-lengths in ciphers by arranging letters in regular patterns.

There is an audible sense of separation achieved by the systematic placement of quarter note rests in the melody line at the beginning of each of the first six measures. This device implies gaps between coded words or phrases. The odd placement of a double bar at the end of measure six is conspicuous because such a feature usually appears at the end of a movement rather than so close to its beginning. The number of melody notes in these opening six bars is 24 is also remarkable because the complete six-word title of the covert Theme has 24 letters. In the original 1899 program note, Elgar asserts that the Enigma Theme held a “dark saying.” The term dark can mean hidden or secret, and a saying consists of words and phrases. Based on these and other observations, I reasoned that Elgar embedded a music cryptogram in the opening measures of the Enigma Theme that definitively resolves his melodic riddle. Contrary to the complaints of scholars insisting that he absconded with his secret to the grave, Elgar concealed the answer within the question itself in the form of a music cipher.

An intense three-month period of cryptanalysis ensued from December 2009 through February 2010 as I feverishly experimented during every free moment with various music ciphers to unlock Elgar’s “dark saying.” Time and again my efforts crashed and receded in failure from this seemingly impregnable seawall. Again I prayed for the Lord’s wisdom and guidance to help me unravel this seemingly impenetrable cipher. 373 days after my personal Enigma Day in February 2009, my second great epiphany arrived on February 10, 2010. It was on that date when it suddenly dawned upon me that Elgar employed melody and bass note pairs to encode his “dark saying” using a Polybius box cipher key, something akin to a chessboard or checkerboard grid.

The detection and decryption of this elaborate music cryptogram documents how Elgar rearranged the 24 letters of the full six-word German title of the covert Theme into short phonetically rendered words and phrases in three different languages: English, Latin, and what he reasonably believed to be Aramaic (but turns out to be Hebrew). In all, there are four different languages in this cipher — English, Latin, German, and Aramaic. Note how the first letters of these four languages form an acrostic anagram of Elgar. In a brilliant but stealthy display, Elgar signed his cipher using a code wrapped within another. Now I had confirmation of my discovery from the hand of Elgar himself, signed, unsealed, and decoded.

One would expect to detect and decrypt the most elementary ciphers in the Enigma Variations first, then progress up the stairwell of complexity to crack the most difficult last. My experience was just the opposite, making my discovery and decoding of the most sophisticated of all the ciphers in the Enigma Variations hugely counterintuitive. A major advantage working in my favor was that I knew the number and type of plaintext letters to assign to the 24 melody notes within the Enigma Theme’s opening six bars. A frequency analysis of the melody/bass note pairs was instrumental in quickly narrowing down my options until Elgar’s “dark saying” first mentioned in the original 1899 program note, emerged from the shadows.

I submitted an early draft of my paper about the Enigma Theme Polybius box cipher to Craig P. Bauer, the editor of the journal Cryptologia. After thoughtful consideration, he declined to publish it in his august journal. Bauer would later devote an entire chapter to Elgar’s command of cryptography in his 2017 book Unsolved! The History and Mystery of the World’s Greatest Ciphers from Ancient Egypt to Online Secret Societies. In chapter 3, Bauer focuses particular attention on the Dorabella Cipher and Elgar’s masterful decryption of a variant of the Polybius square cipher known as a Nihilist cipher. Elgar definitely studied the Polybius box cipher at least two years before he embarked on the Enigma Variations because his personal library includes a series of four articles collectively titled Secrets in Cipher by John Holt Schooling which first appeared in various 1896 issues of The Pall Mall Magazine. Schooling’s fourth and final installment concludes with an in-depth look at the Polybius box cipher and a supposedly insoluble Nihilist permutation. When I first hit on Elgar’s adaptation of the Polybius square to music using melody and bass note pairs, I knew nothing at all about the Greek historian Polybius or his ingenious cipher. Looking back it is clear that I was the beneficiary of divine providence in resolving such a colossal conundrum.

Undeterred by the chronic skepticism of career academics, I applied to my alma mater for a Time-Out Grant to fund my research. Alumnae of Vassar College approaching their 40th birthday may apply for this special grant to take a year off “to make a difference in the world.” In my application, I explained how I planned to further my study of the Enigma Variations with the objective of preparing a book and website to share my growing body of work that upends decades of Elgar scholarship. My application was summarily denied. In their declination letter, the committee acknowledged awarding the grant to a monk who had resided in a Tibetan Buddhist monastery for 23 years and desired (ironically as that may sound) to test her beliefs in the outside world. As I perused the public profiles of previous Time-Out Grant recipients, it quickly became apparent they were all women. I did not realize that white Christian males were placed on a permanent time-out from consideration for Vassar College’s Time Out Grant.

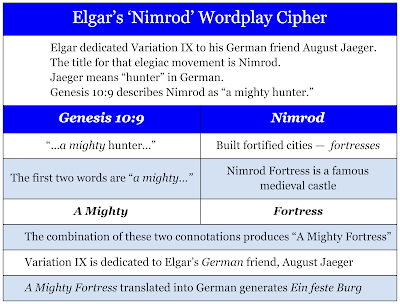

Repeated attempts to advance and share my discoveries with the aid of academia and established publishers with an interest in Elgar were greeted with disbelief and a chorus of “Noes.” A mountain of dubious doubters blocked my path, so I decided to speak to my mountain in faith and cast it into the depths of the sea. My decryption of the Enigma Theme Music Box Cipher revealed Elgar’s covert signature, and that was all the confirmation I required to proceed. The publication of this groundbreaking discovery has become my most popular post. A cornucopia of other incredible cryptograms has since emerged from the shadows. One remarkable example is a wordplay cipher based on the unusual name Nimrod.

Emboldened by these discoveries, I decided to take and make my case directly before the world using Google’s free platforms Blogger and YouTube. In mid-September 2010 I began releasing the first chapters of my book Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed on this blog, and soon added companion music video exhibits on my YouTube channel.

Media coverage of my research began as a trickle in March 2009 with a brief article by Tim Smith, the fine arts critic of The Baltimore Sun. Dr. McClelland made passing mention of my melodic solution in the July 2009 issue of The Elgar Society Journal. The popular blog Boing Boing drew favorably highlighted my discoveries in June 2013. The website Unsolved Problems released my paper Elgar’s Music Box Cipher in August 2015. In 2016 my research was described in an article about the Enigma Variations by Classical Notes. A major coup came in February 2017 with the release of Daniel Estrin’s exposé “Breaking Elgar’s Enigma” in The New Republic magazine. The local outlet D Magazine quickly followed suit with their article “Was This Famous Classical Music Puzzle Solved In Plano?” The American Society of Cinematographers refers to my research in their May 2017 article “Edward Elgar's Enigma.” NPR aired Elgar's 'Enigma’ Still Keeps Music Detectives Busy in March 2018. Two months later, Love + Radio released their program Counter Melody in May 2018. More media coverage will inevitably follow as the bona fides of my discoveries become more widely acknowledged and accepted.

Ten years and counting with 131 posts and over 405,000 page views in the rearview mirror, this blog shows no signs of stopping on the eve of the 120th anniversary of the historic premiere of the Enigma Variations this June. The campaign to disseminate my research has proven wildly more successful than I had ever dreamed or anticipated. As Dryden’s character opines in the 1962 classic film Lawrence of Arabia, “Big things have small beginnings.” With feelings of nostalgia mingled with optimism, I look forward to attending the North American Branch Conference of The Elgar Society this May in San Francisco. That harbor city is where my enigmatic voyage commenced in a spirit of bohemian humor and continues in deep seriousness.

With the unmasking of A Mighty Fortress as the covert Theme, Elgar’s seemingly ordinary remarks to F. G. Edwards in a letter dated October 21, 1898, regarding a projected “Gordon” symphony assume a renewed significance. He wrote, “’Gordon’ simmereth mighty pleasantly in my (brain) pan & will no doubt boil over one day.” Something symphonic did indeed erupt on that fateful day when later that evening Elgar first performed the Enigma Theme at the piano for his wife. The appearance of the word mighty in his correspondence about a projected symphonic work on that day of days is an extraordinary slip of the pen. To learn more about the innermost secrets of Elgar's sublime symphonic homage to cryptography, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.