Getting the question right is the answer.

Ed Newton-Rex recently proposed the Stabat Mater by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi as the missing melody to Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations. For this new melodic solution to be correct, it must satisfy six conditions delineated publicly and in writing by Elgar. These six criteria come from four primary sources – the 1899 program note, an October 1900 interview in The Musical Times, Elgar’s first biography published in 1905, and descriptive notes for the Aeolian Company's pianola rolls issued in 1929 and later published by Novello in 1947 under the title My Friends Pictured Within. Those six conditions are:

- The principal Theme is famous.

- The principal Theme is not heard.

- The Enigma Theme is a counterpoint to the principal Theme.

- Fragments of the principal Theme are present in the Variations.

- The principal Theme is a melody that can be played “through and over” the whole set of Variations, including the entire Enigma Theme.

- The Enigma Theme comprises measures 1 through 19.

Does Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater fulfill these precise parameters of the puzzle? Or does it fall short of Elgar’s exacting specifications like so many other prior candidates?

Condition 1

Elgar’s first condition demands that the covert principal Theme be famous. Does Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater satisfy that condition? Have you ever heard of Pergolesi or listened to his Stabat Mater? More importantly, was it popular when Elgar composed the Enigma Variations in 1898-99? This writer must confess to being unaware of that composer and particular work until encountering Rex’s theory.

Writing for The Times, Richard Morrison cast doubt on whether Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater was “well-known” during the late 19th century when Italian baroque choral music was rarely performed in England. During that era, England’s concert halls were dominated by a juggernaut of German artists like the conductor Hans Richter, violinist Joseph Joachim, and composers like Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Wagner. At this time, there was a longstanding English tradition of recruiting great German composers and musicians and championing them as ersatz-natives such as Handel, J. C. Bach, Mendelssohn, Joachim, Richter, and others. This identification with German maestros was undoubtedly promoted by the House of Windsor who spoke German and traced its royal lineage back to Germany.

The Stabat Mater is a Roman Catholic hymn dating from the 13th century that depicts the suffering of Mary at the crucifixion of Jesus. It has been set to music by Western composers such as Palestrina (~1590), Vivaldi (1712), Domenico Scarlatti (1715), Alessandro Scarlatti (1723), Pergolesi (1736), Joseph Haydn (1767), Giuseppe Tartini (1769), Rossini (1831–41), and Antonín Dvořák (1876–77). At the Birmingham Festival in September 1884, Elgar served as a sectional first violinist under the baton of Dvořák who conducted his own Stabat Mater and Symphony No. 6 in D major. In a letter to Dr. Buck, Elgar praised Dvořák’s music, “It is simply ravishing, so tuneful & clever & the orchestration is wonderful; no matter how few instruments he uses it never sounds thin.” In stark contrast, Elgar never wrote anything commending the music of Pergolesi or his Stabat Mater.

Service orders between 1850 and 1880 verify that Pergolesi’s music was performed at St. George’s Catholic Church in Worcester where Elgar and his family regularly attended mass. It is probable Elgar heard Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater at one or more of those services. His father served as organist at St. George’s where Elgar began assisting him in 1872 and briefly succeeded him at that post from 1885-89. Other than a perfunctory reference to Pergolesi’s church music in The Cambridge Companion to Elgar and Elgar: An Extraordinary Life, one is hard-pressed to find any other mention of him or his music in other books or scholarly articles exploring Elgar’s life and works. Pergolesi’s name does not even grace the pages of Jerrold Northrup Moore’s magnum opus Edward Elgar: A Creative Life. That is far from the case for Bach, Wagner, and Richter.

There is no question that Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater was familiar in Catholic church settings during Elgar’s lifetime, but it was certainly not popular or performed in England’s great concert halls when Elgar conceived and birthed his Enigma Variations. In defense of his thesis, Rex cites a passage from Leslie Norton’s Leonide Massine and the 20th Century Ballet that claims Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater “was the most frequently printed single work of the eighteenth century.” Perhaps Rex mistook the 1800s for the 18th century which began in January 1701 and ended in December 1800. This is far removed from when Elgar composed the Enigma Variations in 1898-99 at the tail end of the 19th century. While Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater enjoyed some success as a single publication over a century before Elgar wrote his Enigma Variations, that is hardly a contemporaneous indicator of its popularity in 1898. Even Norton concedes, “Although lacking in profundity, Pergolesi’s music is attractive for its sweetness and animation . . .” That does not sound like a ringing endorsement of a great composer who would merit Elgar’s esteem and attention.

There is nothing in the historical record to show that Elgar ever extended to Pergolesi the same awe and respect he exuded for Johann Sebastian Bach, Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Giacomo Meyerbeer, or Richard Wagner. Pergolesi was never openly acknowledged as a great composer by Elgar, his music merits scant mention in Elgar scholarship, and his Stabat Mater was unpopular and rarely performed at the time the Enigma Variations was written. For these reasons, Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater fails the litmus test of fame imposed by Elgar’s first condition.

Condition 2

Elgar’s second condition specifies the covert principal Theme is not heard. Although Rex does not explicitly address this condition, it is implied by his acknowledgment the Enigma Theme is a counterpoint to the covert principal Theme. Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater is not heard within the Enigma Theme and consequently would theoretically satisfy this second condition.

Condition 3

Elgar’s third condition requires that the Enigma Theme be a counterpoint to the principal Theme. Rex accepts this condition but distorts it in two critical ways. First, he flips Elgar’s formula by placing the Enigma Theme above rather than below Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater. Second, he strips the Enigma Theme of its accompaniment and substitutes that for the Stabat Mater. These two material changes are inconsistent with Elgar’s published statements describing the contrapuntal relationship between the covert principal Theme and the Enigma Theme.

Elgar explained in published remarks that the covert Principal Theme plays above the Enigma Theme. He first articulated this condition in the program note for the June 1899 premiere:

The Enigma I will not explain – its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’, but is not played…So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some later dramas – e.g., Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’ – the chief character is never on the stage.

Elgar states the Theme plays “through and over” the entire set of Variations but is not heard. In a musical context, Merriam-Webster defines theme as “a melodic subject of a composition.” By referring exclusively to the principal Theme’s melody, Elgar precludes from consideration its accompaniment. Merriam-Webster defines over as “above.” A list of synonyms for over are “above, on top of, higher than, higher up than, atop.” Merriam-Webster defines through as “from the beginning to the end.” A list of synonyms for “through” is “the whole time, all the time, from start to finish, without a break, without an interruption, uninterrupted, nonstop, continuously, constantly, throughout.” As intimated by Elgar’s reference to Maeterlinck’s plays, the main character of the covert principal Theme is its melody.

Within a year after the premiere of the Enigma Variations, Elgar reiterated this proviso for an interview published in the October 1900 issue of The Musical Times:

In connection with these much discussed Variations, Mr. Elgar tells us that the heading ‘Enigma’ is justified by the fact that it is possible to add another phrase, which is quite familiar, above the original theme that he has written. What that theme is no one knows except the composer. Thereby hangs the ‘Enigma.’

For a second time, Elgar advised the covert principal Theme plays “above” the Enigma Theme and the accompaniment he provided. From two primary sources, Elgar specifies that the secret principal Theme plays alone above the Enigma Theme as a whole. Rex upends this condition by insisting just the opposite, that “when auditioning hidden themes, we should be playing the hidden theme and humming the Enigma theme over the top.” Rex’s misreading of Elgar’s third condition results in a melodic mapping of the Enigma Theme’s first six bars stripped of its accompaniment and played above — not below — Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater. Without devoting any attention to some sordid dissonance intervals formed between the Enigma Theme and the Stabat Mater, such a melodic mapping constitutes a flagrant violation of Elgar’s third condition.

Rex’s misreading of Elgar’s definition of the contrapuntal relationship between the covert principal Theme and the Enigma Theme is further highlighted by an example of Elgar’s counterpoint produced shortly after completing the Enigma Variations in July 1899. Elgar composed his concert overture Cockaigne Op. 40 between 1900 and 1901. For this work, he devised the lover’s theme as a counterpoint to another famous melody, the “Wedding March” from Mendelssohn’s incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This example of Elgar’s contrapuntal thinking illustrates how Mendelssohn’s famous tune is played alone above the lover’s theme and its native accompaniment. There are distinct divergences between Elgar’s counterpoint and the famous source melody. As Mendelssohn’s theme descends, Elgar’s countermelody typically rises in contrary motion. When Mendelssohn’s melody ascends upward, Elgar’s tends to drift downward. These essential elements of Elgar’s contrapuntal style are conspicuously absent from Rex’s mapping of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater below the Enigma Theme’s melody.

Elgar’s method for constructing an original counterpoint to Mendelssohn’s famous tune meshes perfectly with his description of how the covert principal Theme plays “through and over” the Enigma Theme and its accompaniment. This contrapuntal technique is the same applied to the construction of the Enigma Theme and its accompaniment as a counterpoint to the covert principal Theme. Rex’s misreading of Elgar’s third condition produces multiple infractions with his mapping of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater below the Enigma Theme stripped bare of its accompaniment. Superimposing the melody from Pergolesi's Stabat Mater “through and over” the complete and intact Enigma Theme fails to realize a credible contrapuntal fit, even when accommodating the Enigma Theme's alternating minor and major modes. In light of the available evidence, Elgar’s third condition remains unfulfilled by Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater.

Condition 4

Elgar’s fourth condition indicates there are fragments of the principal Theme within the Variations. This criterion is implied by an exchange in 1923 between Elgar and Troyte Griffith, the friend portrayed in Variation VII. Troyte asked if the absent melody was God save the King. Elgar replied, “No, of course not; but it is so well-known that it is extraordinary no one has spotted it.” Besides establishing its fame as required by the first condition, such a response implies that fragments of the absent Theme are present in the Variations, for otherwise there would be nothing to spot. This hunch is bolstered by the original program note that describes the link between the absent Theme and the Variations as being “. . . often of the slightest texture. . .” Merriam-Webster defines slight as “very small in degree or amount,” and one definition for texture is “the various parts of a song . . . and the way they fit together.” Elgar’s judiciously parsed words specify that an identifiable bond between the Variations and the absent Theme is made up of short sequences of shared notes or fragments. This condition is further alluded to by brief four-note fragments quoted in Variation XIII from Mendelssohn’s concert overture Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage (Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt), Op. 27.

Although Rex does not directly cite Elgar’s fourth condition, he does attempt to identify note sequences within the Enigma Theme from Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater. For example, he points out that the first six notes from the Enigma Theme’s bass line appear in the sequential 2-3 suspensions from the Stabat Mater’s two vocal parts. He further observed that every note of the opening motif from the Stabat Mater appears sequentially in one or another of the orchestral parts from Variation I. These reconstructions rely on selectively cherry-picking notes from multiple voices from the Stabat Mater to approximate one or more instrumental parts in the Enigma Theme or Variation I. What Rex fails to identify are any recognizable melodic fragments from Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater in any single instrumental line from the Enigma Theme’s orchestral score or any of the ensuing movements. Without such evidence, Elgar’s fourth condition remains unfulfilled.

Conditions 5 and 6

Elgar’s fifth condition states that the principal Theme is a melody that can be played “through and over” the whole set of Variations including the entire Enigma Theme. The lynchpin of Rex’s thesis rests on confining his topsy-turvy counterpoint to the opening six bars of the Enigma Theme. One can hardly blame Rex for acceding to the conventional wisdom that mischaracterizes these opening bars of the Theme as the “Enigma.” Even Julian Rushton grants credence to this unmerited speculation by writing, “‘Enigma’ is not the title of the composition, but an emblem for the theme — perhaps only for its first few bars . . .” Such a truncated perspective is endemic to virtually all prior attempts to produce some semblance of a counterpoint between a famous tune and the Enigma Theme. By focusing his efforts on fitting a tune with the Enigma Theme's opening six bars, Rex is treading a well-worn and ephemeral path to nowhere.

Elgar’s sixth and final condition expressly defines the Enigma Theme’s length at nineteen bars. In My Friends Pictured Within published by Novello in 1947, Elgar writes regarding Variation I, “There is no break between the theme and this movement.” Variation I begins in measure 20. In this context, Elgar’s straightforward statement designates bar 19 as the conclusion of the Enigma Theme. This observation is supported by a double bar in bar 19 separating the Enigma Theme from Variation I.

Rex relies on the same type of double bar line at the end of measure 6 to limit his counterpoint to the opening G minor section of the Enigma Theme. However, the presence of that same double bar line at the terminus of bar 19 confirms the Enigma Theme ends where Variation I begins precisely as Elgar described it. Any proposed melodic solution that fails to take into account the Enigma Theme’s full complement of nineteen measures may be confidently dismissed as incomplete and inconsequential. Pergolesi's Stabat Mater does not measure up to Elgar's prescribed target by a factor of thirteen bars.

Rex questions Elgar’s coherent definition of the Enigma Theme’s length by contending he did not really mean what he wrote. Rex surmises, “In . . . describing the first Variation, he [Elgar] says ‘there is no break between the theme and this movement’, indicating the theme he is referring to here is the opening 19 bars — but in this context it seems likely he is simply giving a name to the untitled opening movement, for which ‘theme’ is the natural choice, rather than providing a conflicting opinion about what he considers the Enigma theme.” This type of dissimulation is to be expected from a criminal defense attorney, not an aspiring musicologist.

Elgar’s straightforward definition of the Enigma Theme’s length is in open conflict with Rex’s truncated revisionism. Rex's mischaracterization of the opening movement as “untitled” does not comport with Elgar’s decision to assign the title “Enigma” to the opening movement on the original Master Score, the official piano reduction, the first published score as well as all of the instrumental parts. It is disingenuous to claim Elgar ascribed that title to only the first six bars when all the available published evidence confirms it is used to identify the whole first movement. Furthermore, melodic elements of the Enigma Theme’s contrasting G major section (bars 7 - 10) turn up repeatedly in the Variations, reinforcing the fact the Enigma Theme continues beyond bar 6. This is an absolute certainty because the opening six measures are restated in a slightly altered form beginning in bar 11. The evidence comports with Elgar’s published definition of the Enigma Theme as forming the entirety of the opening movement concluding in measure 19.

Conclusion

This evaluation of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater revealed it only fulfills one of six criteria given by Elgar that define the special relationship between the covert principal Theme and the Enigma Variations. The first condition specifies that the secret Theme must be famous. Italian Baroque music like Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater was unpopular and rarely performed in England at the close of the nineteenth century when Elgar composed the Enigma Variations. Pergolesi was never classified by Elgar as a great composer, and the absence of Pergolesi’s name in scholarly articles and books concerning Elgar should be sufficient to preclude him and his music from serious consideration.

Rex’s contrapuntal mapping of the Enigma Theme’s melody alone above Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater violates Elgar’s third condition that calls for the opposite approach with the hidden melody played by itself over the Enigma Theme and its organic accompaniment. The length of Rex’s mapping violates Elgar’s sixth condition requiring that the counterpoint continue “through and over” the full nineteen bars of the Enigma Theme. Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater falls short of Elgar’s target by thirteen bars or 68 percent of the movement. The absence of identifiable fragments from the Stabat Mater in any single instrumental line raises doubts about meeting Elgar’s fourth condition. With so many breaches of Elgar’s conditions, Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater may be confidently dismissed as a credible melodic solution to the Enigma Variations.

Ein feste Burg

Rex dismisses Luther’s hymn Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) as the melodic solution because he believes “the tune doesn’t fit well over the main opening theme of the Enigma Variations, and, even at points in the Variations where it can be made to fit, the fit does not come at all naturally.” Does this negative appraisal withstand a fair hearing? A preliminary mapping of Bach’s version devoid of any rhythmic alterations “through and over” the Enigma Theme produces a remarkable horizontal fit with the opening seventeen bars, albeit not entirely free of some unwelcome dissonances. This approach was eventually revised after accounting for Elgar’s definition of the Enigma Theme’s nineteen bar duration, resulting in a retrograde mapping of Ein feste Burg over the entire Enigma Theme free of unseemly dissonant intervals. Such a backward approach was suggested by the Enigma Theme’s ABA’C structure as ABAC is a phonetic version of aback. Elgar cleverly spelled out the nature of his retrograde counterpoint using the structure of the Enigma Theme as a clue. Hearing a theme played backward is an enigmatic experience.

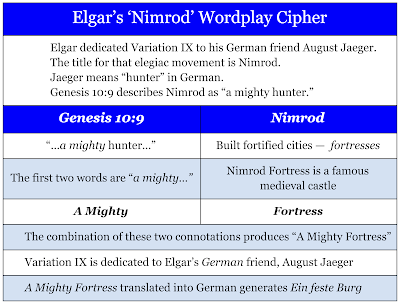

It has yet to be shown how Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater may play “through and over” Variation IX. However, there is a compelling mapping of Ein feste Burg played over Nimrod that Richard Winter-Standbridge proclaimed is as “clear as a pikestaff.” No other melody has ever been successfully mapped over that elegiac movement except for A Mighty Fortress. Elgar’s unusual title for Variation IX turns out to be an exquisite wordplay on the covert Theme’s title. Variation IX is dedicated to Elgar’s friend, August Jaeger, whose last name means “hunter” in German. Nimrod is described in Genesis 10:9 as “a mighty hunter,” and it is incredible that the first two words of the covert Theme’s title — a mighty — precede the English translation of Jaeger’s name. Nimrod was renowned for designing and building fortified cities also known as fortresses.

At Rehearsal 33 where Variation IX begins, the tuning for the timpani encodes the initials for Ein feste Burg. In the span of four quarter beats, those initials appear in Nimrod’s melody as the second (E-flat), fourth (F), and fifth (B-flat) notes. The E-flat and F are on the first and third beats of Rehearsal 33, and the B-flat is on the first beat of the next bar. Those beat numbers (1 and 3) correspond to the Roman numerals of Variation XIII.

Rex’s failure to appreciate a compelling contrapuntal fit between Luther’s hymn and the Enigma Variations leads to a blanket dismissal of numerous cryptograms authenticating Ein feste Burg as the secretive melody. He contends, “It’s a nice idea that Elgar built a complex web of codes of this nature into the Variations, but it seems like it’s almost certainly reading too much into things, especially given that the solution doesn’t meet the fundamental requirement of fitting musically with the Enigma theme.” Before reading too much out of Elgar and his Enigma Variations, Rex should read the recently released book Unsolved! by Craig P. Bauer. An entire chapter is devoted to Elgar’s interest and expertise in cryptography. Bauer begins with the Dorabella Cipher before dedicating considerable attention to Elgar’s meticulous decryption of an allegedly insoluble Nihilist cipher devised by John Holt Schooling for an 1896 issue of The Pall Mall Magazine.

Elgar’s solution to Schooling’s Nihilist cipher is laid out on nine carefully annotated index cards. On the sixth index card where he began to crack the code wide open, he wrote, “Example of working (in the dark).”

It is revealing that Elgar used the word dark as a metaphor for a cipher because that same language appears in the 1899 program note where it cites a “dark saying” in the Enigma Theme. Elgar’s seemingly opaque description of something in the Enigma Theme is coded language for a cipher. “Dark” means hidden or obscured, and a “saying” consists of words and phrases.

The double bar at the end of measure six demarcates an incredible series of music cryptograms within the Enigma Theme. The performance directions in the Enigma Theme’s first measure are an acrostic anagram of “EE’s PSALM”. That is a stunning discovery because the title of the covert Theme comes from Psalm 46. The bar lengths of the Enigma Theme’s A (6) and B (4) sections pinpoint that precise chapter (46). Elgar encodes the word locks in the opening six bars of the Enigma Theme by applying a simple number-to-letter key to the separate note totals for each of the active string parts. Locks are opened by keys, a realization that led to more careful scrutiny of the Enigma Theme’s keys. That opening movement is performed in the parallel major and minor keys of G. In a striking parallel, the accidentals for those two keys furnish the initials for Ein feste Burg. These initials are enciphered throughout the Enigma Variations by a broad spectrum of cryptograms.

Elgar’s “dark saying” mentioned in the 1899 program note turns out to be a musical Polybius square cipher formed by pairs of melody and bass notes from the Enigma Theme’s opening six measures. This is the same type of cipher constructed by John Holt Schooling in 1896 that Elgar bragged about solving in his 1905 biography. The detection of this cryptogram was sparked by the realization there are 24 melody notes dispersed over six bars, and 24 letters in the six-word title of the covert Theme. The oddly placed double bar at the end of measure 6 conveniently demarcates the extent of this and other cryptograms. Using the proven code-breaking technique of frequency analysis, it was determined that Elgar rearranged the 24 letters of the covert Theme’s title into a grand anagram of phonetically spelled words and phrases in four distinct languages: English, Latin, German, and Aramaic. The solution is confirmed by the first letters of those four languages which are an anagram for ELGAR. In a brilliant cryptographic feat, Elgar signed the decryption using a code wrapped within another. A Polybius square is also known as a box cipher. In the context of the Enigma Theme, Elgar’s “dark saying” may be labeled literally as a Music Box Cipher. Such a playful description bears all the hallmarks of Elgar’s known affinity for wordplay.

Rex made no attempt to search for cryptograms because he convinced himself that there were none to discover. This is the same sin of omission committed by Julian Rushton. In scorning complexity in favor of simplicity, Rex elevates the principle of Occam’s razor at the price of slitting his own analytical wrists. The simplest explanation is not always the best, particularly one involving a set of symphonic Variations based on a Theme called Enigma. Consulting the dictionary definition of enigma verifies that it means “something hard to understand or explain.” Why anyone would ever insist that the melodic solution to the Enigma Theme would be simple or straightforward is a genuine enigma.

Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott is commonly known as A Mighty Fortress and is Luther’s most famous and performed hymn. Based on Psalms 46, Ein feste Burg was composed around 1527 and sung to great acclaim at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 where Luther defiantly uttered his famous words, “Here I stand. I can do no other.” It has been translated into English at least seventy times, and over the past five centuries has been performed around the world in many other languages. It is generally acknowledged Elgar was an avid disciple of the German School. His chief musical role models were Bach, Schumann, and Wagner.

If there ever were a melodic cornerstone to the German School, it would have to be Ein feste Burg as it is quoted in the music of J.S. Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Schumann, Nicolai, Raff, Wagner, Liszt, and Reinecke. No other melody is cited by the great German masters so frequently or famously. As late as March 1853, Robert Schumann (Elgar’s ‘ideal’) was planning to compose a sacred oratorio about Martin Luther featuring Ein feste Burg in the final climactic chorus. If Ein feste Burg were epic enough to attract the attention of some of the greatest composers of the German school, particularly those whom Elgar venerated and emulated in his own works, then the magnetic allure of that rousing hymn would not have escaped Elgar’s notice.

There is no doubt that Martin Luther’s hymn Ein feste Burg was famous when Elgar composed the Enigma Variations in 1898-99. Hans Richter began conducting regular concert series in 1877 at St. Jame’s Hall in London that featured Wagner’s music. Richter was Wagner’s protégé and enjoyed immense popularity with British audiences. These and other concerts led by Richter included Wagner’s Kaisermarsch, a piece that quotes Luther’s Ein feste Burg. One of numerous instances took place when Richter conducted a performance of Kaisermarsch at the Crystal Palace 0n November 17, 1899. Five months earlier in June 1899, Richter conducted the premiere of the Enigma Variations.

There is another explanation for why Elgar suspected the hidden theme would soon be exposed. He was profoundly grateful to Richter for agreeing to conduct the premiere of the Enigma Variations. As a token of his gratitude, Elgar presented him with a copy of Longfellow’s Hyperion. In a letter accompanying the book, Elgar wrote, “I send you the little book about which we conversed & from which I, as a child, received my first idea of the great German nations.” Little did Richter know the secret melody to the Enigma Variations and its composer are mentioned within its pages. No wonder Elgar thought the answer would soon be discovered, for he literally gave it away to an eminent musician who should have recognized it if he ever bothered to read the book. Being a renowned conductor in great demand, there is no indication he ever did. Elgar proved that sometimes the best way to hide something is in plain sight.

In the Royal life of England, Ein feste Burg was given a prominent place of honor as shown by the coronations of 1902 and 1911, global events in the Edwardian era attended by leaders and representatives from around the world when the sun did not set on the British Empire. At the 1902 coronation of King Edward VII, Ein feste Burg was performed multiple times, first as a hymn during the processional, and later in Wagner’s Kaisermarsch. This same hymn was performed at the 1911 coronation of King George V and Queen Mary, again as part of the processional music and also in the homage anthem composed by Sir Frederick Bridge “making liberal use of Ein’ feste Burg.”

Wagner conducted his Kaisermarsch at Royal Albert Hall in May 1877. Hubert Parry attended a rehearsal on May 7, and recounted in his diary, “The Kaisermarsch became quite new under his influence and supremely magnificent. I was so wild with excitement after it that I did not recover all the afternoon.” Parry later played a role in furthering Elgar’s career as a composer. Elgar would express his gratitude by orchestrating Parry’s hymn Jerusalem which is traditionally performed at The Last Night of the Proms.

Elgar certainly heard if not performed Ein fest burg on numerous occasions in the years preceding the genesis of his Enigma Variations partly because of the Bach resurgence that swept England and the rest of the Western world. Bach's works were routinely performed at the Three Choirs Festival beginning in the early 1870s. In 1871 Bach's St. Matthew's Passion was first performed there, and music by Bach and Mendelssohn was commonplace in England throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Elgar played violin in the Festival orchestra in 1878. The Monthly Musical Record documents Bach’s Cantata A Stronghold Sure (Ein feste Burg) was performed at the Three Choirs Festival on September 10, 1890. It was also performed at the 1905 commencement at Yale University when Elgar received an honorary Doctor of Music.

For Elgar to openly acknowledge Ein feste Burg as the source melody to one of his greatest symphonic works would undoubtedly conflict with his Roman Catholicism. This necessitated the veil of secrecy achieved by substituting an ingenious counter melody in place of the original principal Theme. It would be inconceivable for Elgar to openly quote the battle hymn of the Reformation, a work composed by a heretic excommunicated by the Pope. His staunch refusals to reveal the hidden theme begin to make complete sense when considered in this framework. As a form of penance for his indulgence with such a Protestant theme, he promptly composed The Dream of Gerontius shortly after completing the Enigma Variations.

For an October 1911 performance in Turin, Elgar explained in the program note how the Enigma Variations “. . . commenced in a spirit of humor & continued in deep seriousness . . .” Rex fails to address how Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater, a medieval hymn about Mary’s suffering at the crucifixion of Jesus, could possibly entail a scintilla of humor. In contrast, there is a visceral comic element to Elgar’s choice of Luther’s Ein feste Burg as no one would ever guess that a practicing Roman Catholic would contemplate a work composed by a German heretic excommunicated by Pope Leo XIII. There are multiple allusions to Dante’s Divine Comedy in the Enigma Variations that further account for this humor aspect. Elgar’s puzzling description serves as a dual allusion to the Enigma Variations’ ironic covert Theme and a great fount of artistic and spiritual inspiration, The Divine Comedy. Like Luther, Dante was critical of the corruption and hypocrisy of the Roman Catholic Church.

Another compelling reason why Elgar staunchly refused to disclose the identity of the missing principal Theme, particularly after 1914, was its overwhelmingly Teutonic character. Following the deaths and maiming of millions of British soldiers in World War I (1914-1917), anything remotely German was intensely reviled by the people of England. After World War I, there was no possible way for Elgar to divulge the covert Theme to the Enigma Variations without risking his status in British society and the arts. During the war, August Jaeger’s widow changed her last name to Hunter to avoid suspicion, Hans Richter and Max Bruch renounced their honorary doctorates from Cambridge, and Gustav von Holst dropped the “von” from his name.

It would have been social if not artistic suicide for Elgar to acknowledge such a German melody as the inspiration for one of the great English symphonic works. Ein feste Burg was not only the Marseillaise of the Reformation but also a very popular war song among German soldiers. When war between Germany and France erupted in 1870, Ein feste Burg was played in Berlin during a grand concert to commemorate the march on Paris. After taking Paris and concluding a punitive peace, Wager commemorated their victory with his famous Kaisermarsch that liberally quotes Ein feste Burg. In English society, the robust association between Ein feste Burg and the German military was widely recognized.

Dora Penny (1874–1964) was the daughter of the Anglican Reverend Alfred Penny of Wolverhampton. Following the death of his first wife, Reverend Penny wed the sister of William Meath Baker, the person portrayed in Variation IV of the Enigma Variations. Dora made numerous attempts to guess the hidden melody of the Enigma Variations. After speculating in vain, she begged Elgar for the answer. He replied, “Oh, I shan’t tell you that, you must find it out for yourself.” “But I’ve thought and racked my brains over and over again,” she replied. He confessed, “Well, I’m surprised. I thought that you of all people would guess it.”

Concerning her movement, Elgar wrote in 1927 that the “. . . inner sustained phrases at first on the viola and later on the flute should be noted.” His brief remarks draw attention to the inner melody line without providing any explanation. Following the discovery of Ein feste Burg as the covert Theme, the reason becomes perfectly clear. The first four notes of the concluding phrase of Ein feste Burg are quoted twice by that inner countermelody. No wonder Elgar told Dora that of all people she would be the one to correctly guess the melodic solution.

Ein feste Burg is featured in Anglican hymnals of that era while Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater is nowhere to be found. Of all the variations, Dorabella directly quotes the first four notes of Ein feste Burg's concluding phrase, expertly camouflaged in an augmented form by the inner voice. Like those melodic fragments surreptitiously cited in Variation X, the Mendelssohn quotations in Variation XIII are also four notes in length. A prevalent error committed by enigma sleuths is to overlay the opening phrase of a prospective tune with the Enigma Theme’s beginning phrase. Elgar’s retrograde mapping of Ein feste Burg “through and over” the complete 19 measures of the Enigma Theme render all such efforts futile. Rex’s mapping of the opening of the Enigma Theme above Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater is just one more instance of this flawed approach. To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Like my heavenly Father’s gift of salvation, the price is free. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

%22.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment