|

| W. A. Mozart in 3D by Hadi Karimi |

The first real sort of friendly leading I had, however, was from ‘Mozart’s Thorough-bass School.’ There was something in that to go upon—something human. It is a small book—a collection of papers beautifully and clearly expressed—which he wrote on harmony for a niece of a friend of his. I still treasure the old volume.

Edward Elgar in The Strand Magazine (May 1904)

The English composer Edward Elgar (1857–1934) and his wife enjoyed a long weekend visit in mid-July 1897 with the family of Reverend Alfred Penny (1845–1934), the rector of St. Peter’s Collegiate Church in Wolverhampton. Caroline Alice Elgar (1848–1920) was a childhood friend of the Reverend’s wife, Mary Frances Baker, who married the widower in 1895 and became the stepmother of his only daughter, Dora Penny (1874–1964). On their return to Great Malvern, Alice penned a letter thanking the Penny family for their hospitality. Elgar added a short enciphered missive to his wife’s correspondence, addressing it to “Miss Penny” on the back. The incisive salutation is a classic Elgarian pun. “Miss” is an honorific title for an unmarried woman or girl, but it also functions as the verb “miss” to express regret or sadness over a person’s absence. Elgar was clearly missing Miss Penny when he created his cryptographic pièce de résistance. Dora was unable to decipher Elgar’s enigmatic script and filed it away for over 40 years before eventually publishing it in her 1937 biography, Edward Elgar: Memories of a Variation.

Elgar’s coded message to Dora Penny is popularly known as the Dorabella Cipher. The name comes from Variation X of the Enigma Variations (1899), a movement dedicated to her that bears the title “Dorabella.” Elgar procured that playful pseudonym from a soprano role for a young unmarried woman in the opera Così fan tutte by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. An operatic nickname for Dora was befitting because she was an avid vocalist who sang in the Wolverhampton Choir Society and her father’s rectory choir. As she recalled in her biography, “I was so mixed up with tunes in those days; Choral music, Church music, and orchestral music – and my own solo-singing, scenes from opera, songs, ballads –, and so on.” Four months before his visit to her father’s rectory, Elgar penned a letter to Dora in which he humorously comments about her weekly singing practices. He wrote, “Alice tells me you are warbling wigorously in Worcester wunce a week (alliteration archaically Norse).” This amusing excerpt is one of many examples where Elgar employs idiosyncratic spellings in his correspondence.

%20from%20%E2%80%9CMy%20Friends%20Pictured%20Within%E2%80%9D.png) |

| Variation X (Dorabella) from “My Friends Pictured Within” |

The Dorabella Cipher consists of 87 curlicue symbols arranged in three rows of varying character lengths followed by a fourth row providing the date “July 14 [18]97”. There are 29 characters in row one, 31 in row two, 27 in row three, and 8 in row four. A conspicuous dot appears over the sixth symbol in row three. Three others appear in row four with small dots to the right of “1” and “4”, and a larger dot affixed to the bend in “7”. In all, there are 87 symbols, four rows, four dots, four letters, and four numbers on the Dorabella Cipher.

|

| The Dorabella Cipher |

Fortunately for investigators, the key to translating this confounding cast of characters into recognizable cleartext is preserved in one of Elgar’s surviving notebooks. A facsimile of that key is displayed below:

|

| Elgar’s notebook cipher key |

Elgar created three distinct glyphs using the lowercase c as the primary building block. His motive for selecting that particular letter is easy to surmise because c is the initial for cipher and cryptogram. There is persuasive evidence in support of this hypothesis as Elgar wrote some of those identical symbols around the word “Cryptogram” on an index card dating from 1896.

.png) |

| Elgar's “Cryptogram” card with ciphertext (circa 1896) |

With his three prototypes assembled from one, two, and three stacked cs, Elgar systematically arranged them into eight different triplets using various angles and orientations to generate 24 alphabetic avatars. Elgar assigned the English alphabet’s 26 letters to these 24 odd characters by conflating i with j, and u with v. Combining similar glyphs is a standard convention of cryptography. The resemblance of some of Elgar's curlicue characters to the capital cursive “E” from his initials is deliberate, embellishing the cipher with his imprimatur in contrasting guises and angles. Relying on Elgar’s notebook key, the Dorabella Cipher converts into the following cleartext:

Elgar used twenty symbols from his lineup of twenty-four characters, omitting those for m, n, o, and z. The three contiguous absent letters (m, n, o) are an anagram of nom, the French term for “name.” That word appears in nom de plume, a French expression for a pseudonym or pen name. Elgar’s signature is conspicuously absent from his coded missive. Could this nom anagram sourced from his missing letters be a clue that Elgar’s name is hidden within the ciphertext? The absence of these four letters parallels the structural emphasis placed on that number by four rows, four dots, four letters, and four numbers. Elgar is clearly hinting at the importance of the number four. The explanation could be that the fourth letter of the alphabet is D, the initial for Dora, the four-letter name of the recipient of Elgar's message.

Cryptographers are baffled by the Dorabella Cipher’s seemingly incoherent cleartext. In his history of unbroken cryptograms titled Unsolved!, mathematics professor Craig P. Bauer concedes that the Dorabella Cipher appears to be a simple monoalphabetic substitution cipher (MASC) in which one letter is replaced by one symbol. Gaps between words are excised to make the code even more difficult to unravel. Like modern ciphers, ancient Greek and Classical Latin text omit spaces between words in a practice called scriptio continua. Bauer laments that when applied to the Dorabella Cipher, none of the standard techniques for solving a MASC yield any sensible or credible results. Even the most advanced computer programs fail to make any inroads. A limitation of this approach is the presumption that Elgar’s message is a MASC restricted to English. Bauer briefly describes and dismisses purported solutions by Eric Sams, Tony Gaffney, and Tim S. Roberts, before concluding that the Dorabella Cipher has not yet been solved because Elgar’s system of encipherment must be “something more complicated.”

Recent cryptanalysis of the seemingly impregnable Dorabella Cipher determined that its dotted symbols encode solutions in Latin (AMDG) and German (Magd). Elgar penned the Latin abbreviation “AMDG” on some of his master scores as a sacred dedication, most notably The Dream of Gerontius. Used to refer to a young unmarried woman, the German word Magd means “maid” and “virgin.” This solution is consistent with the recipient of Elgar’s coded missive, Miss Dora Penny, the young unmarried daughter of Reverend Penny. The Dorabella Cipher also presents some English words as the note is addressed to “Miss Penny” and the month is shown as “July”. Remarkably, these three languages — English, Latin, and German — are an acrostic anagram of the first three letters of “ELGAR.” The linguistic sophistication of the Dorabella Cipher readily explains why experts failed to penetrate it since they naively assumed it was confined to English. Such a unidimensional mindset is utterly incompatible with an autodidactic polymath like Elgar. Unconventional methods, like Elgar’s odd spellings, are the keys to unraveling the Dorabella Cipher.

Three of the four absent letters (m, n, o, z) from the Dorabella Cipher are an anagram of nom, the French word for “name.” Remarkably, the dot above the sixth character in row three of the Dorabella Cipher pinpoints a familiar nickname for Elgar. Relying on Elgar’s notebook key, the raw decryption of the character below the dot in row three is the letter E. One dot in International Morse Code is also E. Consequently, the dot and the symbol encode Elgar’s initials (EE). Immediately following the encoded E, the next two characters encode the letters d and u/v. The small dot above the ciphertext in the third row tags the text sequence “Edu” which is one of Elgar’s primary nicknames.

Elgar’s wife coined the pet name “Edoo” using the first three letters of the German version of her husband’s forename, Eduard. Elgar assigned this pseudonym to his musical self-portrait in the Enigma Variations (1899), the martial Finale with the title “E. D. U.” Dora Penny was familiar with this pet name as she spent a substantial amount of time around the Elgar family and heard Alice call her husband “Edoo.” This fragmentary decryption confirms that the Dorabella Dots Dedication Cipher is covertly signed by its author. The solution comports with the feasibility of spelling nom from absent letters in the cipher and the glaring absence of Elgar’s signature from his note. The discovery of Elgar’s nickname is consistent with other cryptograms in the Enigma Variations that are similarly tagged by his name or initials.

Far from being a completely random assortment of letters as posited by investigators like Dr. Keith Massey, the cleartext presents a coded form of Elgar’s name expertly woven into the fabric of the cleartext. Elgar made it an obvious place to look because of the anomalous dot above the sixth character in row three. This “EDU” Dot Cipher furnishes the author's signature conspicuously missing from his missive to Miss Penny. It is astonishing that his signature remained undetected since the cipher was first publicized 85 years ago. One reasonably wonders what else the so-called experts failed to detect lurking just beneath the surface of the Dorabella Cipher cleartext. After all, Elgar's encoded signature was not difficult to spot.

A recent reassessment of the Dorabella Cipher uncovered yet another cryptogram connected with the anomalous dots in the fourth row where Elgar dated his mystifying message as “July 14 97”. There is no comma between the day and year, and the century (18) is omitted. One small dot appears next to the upper right of “1”, and another next to the lower right of “4”. There is a third larger dot next to the crook in “7” that constitutes the final character in the cipher. Scanning from left to right, these dotted numerals form the number “147”. The fourth row has four letters (July), four numbers (14 & 97), and three dots. Translating the number eleven into its corresponding letter of the alphabet using an elementary number-to-letter key (1 = A, 2 = B, C = 3, etc.) generates the letter “K.” Uniting that coded letter with the dotted numerals yields “K 147.”

Before attempting to decode the significance of “K 147”, it is first necessary to become acquainted with the work of the Austrian musicologist Ludwig Köchel. He established a chronology of Mozart’s compositions and assigned them sequential numbers. For example, the Requiem in D Minor is Mozart’s 626th work and is assigned the number 626. In 1862, Köchel published a comprehensive listing of all known compositions by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart called the Köchel Catalogue. This first edition remained the standard reference source until undergoing revisions in 1905. Each Köchel number is preceded by his initial “K.” Consequently, “K 147” may be confidently read as “Köchel 147.”

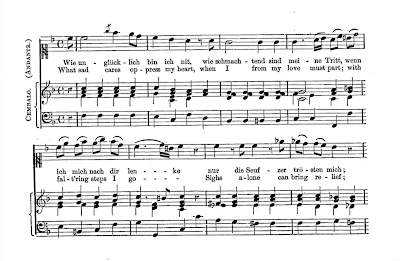

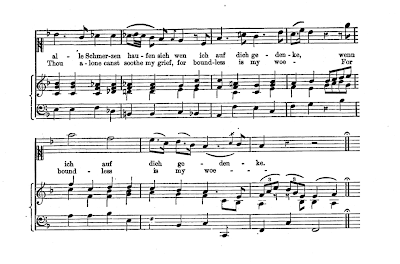

Out of so many diverse possibilities, which one of Mozart’s works is listed by Köchel as the 147th? Could it be a piano sonata, a string quartet, a divertimento, or a symphony? On the contrary, it is a diminutive song for soprano and piano called “Wie unglücklich bin ich nit” (How unlucky I am). At only fifteen bars, it is a “sentimental love song . . . in which the fifteen-year-old Mozart pointedly depicts the sighs of a slighted lover . . .” The ensemble for “Wie unglücklich bin ich nit” is perfectly paired with Dora (a soprano) and Elgar (a skilled pianist and accompanist). Shortly after their first encounter, Elgar played piano for Dora. He soon bestowed on her the nickname Dorabella, a soprano role from Mozart’s Opera Così fan tutte. Elgar clearly associated Dora with Mozart’s music. The discovery of a coded reference to one of Mozart’s songs in the Dorabella Cipher indicates Elgar made this connection shortly after their first meeting at her father’s rectory.

“Wie unglücklich bin ich nit” was composed by Mozart in Salzburg during the summer of 1772. The author of the libretto is unknown and could be Mozart himself. A copy of this song appears in an 1869 book by John Ella published in London called Musical Sketches Abroad And At Home. A talented violinist, Ella inaugurated in 1845 an annual series of instrument and vocal concerts under the title the “Musical Union.” These gatherings often featured established artists who were new to English society. The appearance of Mozart’s song in Ella’s book suggests it was performed at one or more of these concerts. Such attention by a prominent member of London’s musical scene ensured that this gem was not neglected. Dora’s education and extensive experience in the vocal arts likely exposed her to Mozart’s early Lieder including “Wie unglücklich bin ich nit”.

The original German lyrics of “Wie unglücklich bin ich nit” are shown below with an English translation:

Wie unglücklich bin ich nit,

Wie schmachtend sind meine Tritt’,Wenn ich mich nach dir lenke.

Nur die Seufzer trösten mich,

Alle Schmerzen häufen sich,

Wenn ich auf dich gedenke.

How unhappy I am,

How heavy are my steps,

When I direct them toward you.

Only sighs comfort me,

All my worries pile up,

When I think of you.

The lyrics artfully convey Elgar’s sadness over his recent parting from Dora Penny. Such a musical declaration from an older married man to a younger unmarried lady is flattering and suitable following their first meeting. With so many common interests and family connections, Elgar and Dora soon became good friends. Their friendship is movingly depicted by Variation X (Dorabella), a coruscating gem in the Enigma Variations. As one of the longest movements at 73 bars, Elgar clearly longed for Dora’s attention and company.

There is a secret melody that serves as the contrapuntal cornerstone of the Enigma Variations. Dora pleaded with Elgar to share the title of that mysterious melody, but he steadfastly declined her persistent overtures. When she begged for the solution, he replied, “Oh, I shan’t tell you that, you must find it out for yourself.” “But I’ve thought and racked my brains over and over again,” she insisted. He answered, “Well, I’m surprised. I thought that you of all people would guess it.” The reason Elgar suspected Dora, the daughter of an Anglican Rector who actively sang in church, would guess the hidden melody is because it is the famous hymn A Mighty Fortress (Ein feste Burg) by German Reformer Martin Luther. Little did Dora realize that the ending phrase from that Protestant anthem is quoted twice in Variation X by the inner voice. If only she had searched for the mysterious tune’s ending rather than its beginning, she would have soon unmasked the solution for herself, for she sang it many times in church.

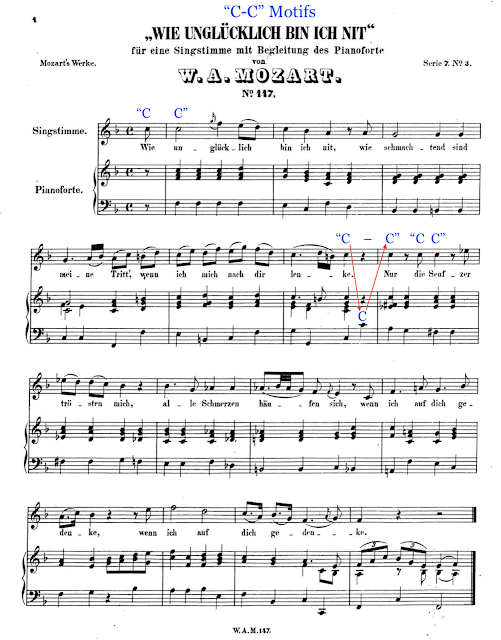

The Enigma Variations conceal a principal Theme that is unheard and yet serves as the contrapuntal cornerstone of the entire work. Like the Variations, Elgar's Dorabella Cipher also harbors a secret melody, one that could be performed by Dora Penny's soprano voice and Elgar's facility at the piano. The Spanish Gaps Code in the Dorabella Cipher encodes the anagram “DORA CC GEM” (Dora sees gem). The dual Cs are remarkable because the soprano opens “Wie unglücklich bin ich nit” with an eighth note C followed by a half note C – two Cs. This “C-C” motif is reprised two more times in Mozart’s diminutive lied with one interrupted by a quarter rest that is conveniently covered by a solitary C in the piano accompaniment. Consequently, the “CC” in the solution to the Spanish Gaps Code cleverly alludes to the opening notes of the secret melody encoded by the Dorabella Cipher.

To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment