During railway journeys amuses himself with cryptograms; solved one by John Holt Schooling who defied the world to unravel his mystery.

The late romantic composer

Edward Elgar excelled in cryptography, the science of coding and decoding secret messages. His obsession with that esoteric discipline merits an entire chapter in Craig P. Bauer’s book Unsolved! Bauer devotes much of the third chapter to Elgar’s brilliant decryption of an allegedly insoluble Nihilist cipher presented by John Holt Schooling in an April 1896 issue of The Pall Mall Magazine. Elgar was so gratified by his solution to Schooling’s purportedly impenetrable code that he specifically mentions it in his first biography released in 1905 by Robert J. Buckley.

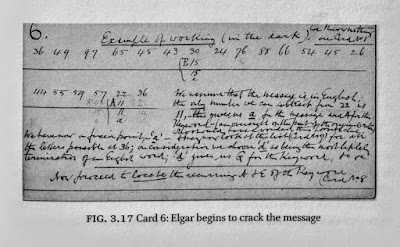

Elgar painted his decryption in black paint on a wooden box, an appropriate medium considering that another name for the Polybius cipher is a box cipher. His methodical solution is summarized on a set of nine index cards. On the

sixth card, Elgar likens the task of cracking Schooling’s cipher to “. . . working (in the dark).” This confirms Elgar used the word “dark” as a synonym for a

cipher.

This parenthetical remark is significant as he employs that same language in the original

1899 program note to characterize his eponymous Enigma Theme. It is an oft-cited passage that deserves revisiting as Elgar lays the groundwork for his tripartite riddle:

The Enigma I will not explain – its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’, but is not played…So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some later dramas – e.g., Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’ – the chief character is never on the stage.

Elgar also uses the words

dark and

secret interchangeably in a letter to

August Jaeger penned on February 5, 1900. He wrote, “Well—I can’t help it but I hate continually saying ‘Keep it dark’—‘a dead secret’—& so forth.” One of the definitions for dark is “secret,” and a saying is a series of words that form a coherent phrase or adage. Elgar’s odd expression — “dark saying” — is coded language for a code. In his oblique manner, Elgar hints there is a secret message enciphered in the Enigma Theme.

A compulsion for cryptography is a reigning facet of Elgar’s

psychological profile. A decade of systematic analysis of the Enigma Variations has netted over ninety cryptograms in diverse formats that encode a set of mutually consistent and complementary solutions. Although this figure may seem astronomical, it is entirely consistent with Elgar’s fascination with ciphers. More significantly, their solutions provide definitive answers to the core questions posed by the Enigma Variations. What is the secret melody to which the Enigma Theme is a counterpoint and serves as the melodic foundation for the ensuing movements? Answer: Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by the German protestant reformer Martin Luther. What is Elgar’s “dark saying” concealed within the Enigma Theme? Answer: A musical Polybius cipher situated in the opening six bars. Who is the secret friend and inspiration behind Variation XIII? Answer: Jesus Christ, the Savior of Elgar’s Roman Catholic faith.

The initials of Elgar’s secret friend are transparently encoded by the Roman numerals of Variation XIII using an elementary number-to-letter key (1 = a, 2 = b, 3 = c, etc.). “X” is the Roman numeral for ten. The tenth letter of the alphabet is J. “III” represents three, and the third letter is C. This cryptanalysis shows that the Roman numerals XIII are a coded form of “JC,” the initials for

Jesus Christ. This is not an isolated instance of this encipherment technique in the Enigma Variations. Elgar uses the same number-to-letter key to encode August Jaeger’s initials in Variation IX (Nimrod). “I” is the Roman numeral for one. The first letter of the alphabet is

A. “X” stands for ten, and the tenth letter is

J.

With the secret friend’s initials thinly disguised by the Roman numerals of Variation XIII, what could be the significance of its cryptic title (***) consisting of three asterisks? That question was resolved in July 2013 by the discovery of the

Letters Cluster Cipher, a cryptogram that revealed the three asterisks represent the initials of Elgar’s mysterious missing melody. Those absent initials are encoded by the first letters from the titles of the adjoining movements: Variations XII (

B. G. N.) and XIV (

E. D. U., and

Finale). These first letters are an acrostic anagram of “EFB,” the initials for

Ein feste Burg. Elgar deftly frames the question posed by the three asterisks with the answer hidden in plain sight.

Elgar’s sketches document five different orderings of the movements for the Enigma Variations. The discovery of the Letters Cluster Cipher verifies these divergent lists were generated to construct that particular cryptogram. This prospect eluded scholars like Julian Rushton who naively insist Elgar lacked the time to construct any ciphers. Rushton’s speculative rush to judgment is unsupported by the known timeline. Elgar began composing the Enigma Variations in earnest on October 21, 1898. The orchestration was completed on February 19, 1899. From inception to completion, the process consumed 121 days or four months. Such a lengthy period afforded more than sufficient time and opportunity for Elgar to indulge his passion for cryptography. Proffering the patently false claim there was inadequate time for Elgar to conceive of any cryptograms within the Enigma Variations conveniently relieves one from the obligation to search for any.

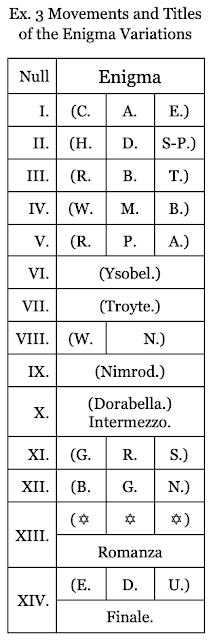

The Letters Cluster Cipher that encodes the covert Theme’s initials is a relatively simple cryptogram. Its discovery precipitated a much broader analysis of all the titles from the Enigma Variations to unmask other meaningful and relevant groupings of adjacent letters. Below is a summary of the Roman numerals and titles of the different movements in the Enigma Variations.

There is no Roman numeral for zero to assign the Enigma Theme that precedes Variation I. For this reason, it is identified by Null, a German term obtained from the Latin

nullum that means “nothing.” That identical word turned up during a conversion between Elgar and his wife on the evening of October 21, 1898, when he first performed the Enigma Theme for her on the piano. After hearing it, Alice commented how

she liked it and

inquired, “What is that?” He replied, “Nothing — but something might be made of it.” Elgar used the word “nothing” to describe the Enigma Theme. At the end of the original score,

he cites a paraphrase from

Torquato Tasso’s

Jerusalem Delivered that also employs the word “nothing.” He wrote, “Bramo assai, poco spero, nulla chieggio” (I desire much, I hope little, I ask nothing). The Italian word

nulla is nearly identical to

null, its German equivalent.

The discovery of the Letters Cluster Cipher fueled the hypothesis that Elgar may have encoded other terms within the Enigma Variations’ titles. These additional words would be connected to the

absent Principal Theme, the Enigma’s “dark saying,” and the secret friend commemorated in Variation XIII. This encipherment technique is markedly dissimilar from Stephen Pickett’s surgical cherry-picking of individual letters from titles and names allegedly associated with different movements to jerry-rig a presumed solution for the absent Theme. Given an adequate supply of letters, it is possible to reconstruct almost anything. The key difference between Pickett’s approach and this methodology is that it is narrowly restricted to smaller groupings of adjacent title letters.

A

systematic analysis of proximate letters from the titles netted thirty different terms related to the riddles posed by the Enigma Variations. The mechanism for this particular cipher hinges on proximate title letters to form relevant words and names. The solutions expertly interwoven within the titles coherently relate to the riddles posed by the Enigma Variations. One example is the title

Christ. This term is spelled by the first initials of Variations I through III (CHR), the Roman numeral I, and the third initials from Variations II and III (ST). Remarkably, the initials CHR and ST are sequential and align in two neat parallel rows.

The discovery of the covert Theme’s initials and secret friend’s title embedded among proximate letters from the Enigma Variations’ titles spurred a renewed search for the hidden melody’s name. Remarkably, it is feasible to reconstruct the common three-word German title for the secret melody from adjacent title letters. The first word of that Teutonic title is conveniently nestled within the Theme’s name, Enigma. A Germanic context is affirmed by how that word was

penciled on the Master Score by Jaeger, the only German friend portrayed in the Variations. The word enigma is also spelled the same way in English and German. The first three contiguous letters of Enigma are an anagram of Ein. There is a second way that word is spelled out by proximate title letters in the Theme and Variation I. “EIN” may also be fashioned from the initial

E for

Enigma, the initial

N for

Nulla, and the Roman numeral for Variation I. It is contextually appropriate that there is a coded link between the first word of the Enigma Variations and the first word of the covert Theme’s title.

Contiguous initials from Variations I-III and XIV furnish the letters needed to spell

FESTE, the second word from the hidden Theme’s German title. Although Variations I and XIV are not neighboring movements, they are intimately connected for three reasons. First, these two movements are musical portraits of Elgar (XIV) and his wife Caroline Alice Elgar (I). Second, this musical union is affirmed by a partial restatement of

Variation I in XIV. Third, Elgar is identified by a phonetic rendering of “Edoo” (E.D.U.), a pet name Alice coined from the German spelling

Eduard. Like

Enigma, “Edoo” is distinctly Germanic. The first initials from the titles of XIV (E and F) and third initials of I (E), II (S), and III (T), are an anagram of

FESTE. Alternatively, the

E in Variation XIV could be substituted with the

E from

Enigma. However, the

E from

Enigma was skipped in this instance as it is already used as part of the first word in the title (EIN).

Neighboring initials from Variations XII, XIII, and XIV provide the letters required to spell BURG. The first and second initials of XII (B. G. N.), the only known initial from XIII (Romanza), and the third initial of XIV (E. D. U.) are an anagram of BURG. Elgar’s phonetic rendering of Alice’s nickname “Edoo” as “E. D. U.” furnishes the crucial adjacent U to complete the spelling. Like the covert Theme’s title, Elgar’s pet name is German.

This cryptanalysis determined that it is feasible to assemble the three-word German title of the covert Theme from adjacent letters in the titles of the Enigma Variations. The first (EIN) is an anagram of the first three letters in Enigma. Alternatively, it may be fashioned from the E in Enigma, N from Nulla, and I from Variation I. The second (FESTE) is encoded by proximate title letters in Variations I, II, III, and XIV. The third (BURG) is enciphered by adjacent title letters in Variations XII, XIII, and XIV. A discernable German antecedent furnishes a part of each word in the decryption. This is the case because the titles of the Theme (Enigma) and Variation XIV (E. D. U.) are Germanic. The distance between Variations III and XII was ostensibly intended to foil recognizing the covert Theme’s name spliced in among the titles of the Enigma Theme, Variations I through III, and XII through XIV.

Elgar expertly interlaced the covert Theme’s title within particular titles of the Enigma Variations using anagrams of adjacent letter groupings. Eight titles from seven contiguous movements are required to construct this particular cryptogram. There is a distinct symmetry as it spans the foundational Theme, the first three variations, and the final three movements. The prominence of two threes suggests a coded version of Elgar’s initials (EE) because that numeral is the mirror image of a capital cursive E. A coded form of Elgar’s dual initials is also detectable in the first and final movements, Enigma and E. D. U.

Could there be yet another layer to this proximate title letters cipher that encodes the title of the covert Theme? A number-to-letter key converts numerals into their corresponding letters of the alphabet. For example, the number one becomes the letter A, the number two the letter B, and so on. Applying this key to the Roman numerals of the movements required to assemble the title of the covert Theme produces the plaintext “ABCLMN” as shown below:

I = A

II= B

III = C

XII = L

XIII = M

XIV = N

The Enigma Theme has no Roman numeral and consequently is assigned a null or zero. The glyph for zero (0) duplicates the letter O. This completes the list of seven number-to-letter conversions in alphabetical order as “ABCLMNO.” When treated as an anagram, those letters may be rearranged as “BLAC NOM.” The first term is a phonetic spelling of black with the letter k absent. It was observed earlier that Elgar generated a phonetic spelling of “Edoo” as “Edu.” Phonetic spellings are an idiosyncrasy of his correspondence. Some examples of these inventive spellings are listed below:

- Bizziness (business)

- çkor (score)

- cszquōrrr (score)

- fagotten (forgotten)

- FAX (facts)

- frazes (phrases)

- gorjus (gorgeous)

- phatten (fatten)

- skorh (score)

- SSCZOWOUGHOHR (score)

- Xmas (Christmas)

- Xqqqq (Excuse)

- Xti (Christi)

A synonym for

black is

dark, a term Elgar used to denote a cipher. An office that specializes in encoding and decoding secret messages is called a

Black Chamber. The second term “NOM” is an exact spelling of the French word for

name.

This word is found in such expressions as “nom de plume” and “nom de guerre.” Consequently, the anagram “BLAC NOM” may be translated as “Black Name.” The complete French translation as “Nom Noir” is alliterative. The ancillary decryption “Black Name” is an apt description for a concealed title. This decryption suggests a password key for pinpointing the specific movements required to reconstruct the covert Theme’s title from contiguous title letters. In his 1899 program note,

Elgar cites the French titles of two plays by Maurice Maeterlinck. To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on

Patreon.