During railway journeys amuses himself with cryptograms; solved one by John Holt Schooling who defied the world to unravel his mystery.

It is fifty years since you, in Regent Street, purveyed five violin pieces to a “prescription” by Pollitzer for me. I remember the pride & pleasure I had in presenting the “order”.

Elgar in a letter to Charles Volkert, the head of Shott Music (May 30, 1927)

The late romantic composer Edward Elgar excelled in cryptography, the science of coding and decoding secret messages. His obsession with that esoteric discipline merits an entire chapter in Craig P. Bauer’s book Unsolved! Bauer devotes much of the third chapter to Elgar’s meticulous decryption of an allegedly insoluble Nihilist cipher presented by John Holt Schooling in the April 1896 issue of The Pall Mall Magazine. A Nihilist cipher is based on a Polybius square key. Elgar was so gratified by his solution to Schooling’s purportedly impenetrable code that he specifically mentions it in his first biography released by Robert J. Buckley in 1904.

Elgar painted his decryption in black paint on a wooden box, an appropriate medium considering that another name for the Polybius square is a box cipher. His process for cracking Schooling’s cryptogram is summarized on a set of nine index cards. On the sixth card, Elgar likens the task to “. . . working (in the dark).” It is significant that he used the word “dark” as a synonym for cipher.

This parenthetical remark is revealing as he employs that same language in the original 1899 program note to characterize his eponymous Enigma Theme. It is an oft-cited passage that deserves revisiting as Elgar lays the groundwork for his tripartite riddle:

The Enigma I will not explain – its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’, but is not played . . . So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some later dramas – e.g., Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’ – the chief character is never on the stage.

Elgar uses the words dark and secret interchangeably in a letter to August Jaeger penned on February 5, 1900. He wrote, “Well—I can’t help it but I hate continually saying ‘Keep it dark’—‘a dead secret’—& so forth.” One of the definitions for dark is “secret,” and a saying is a series of words that form a coherent phrase or adage. Elgar’s odd expression — “dark saying” — is coded language for a cipher. In an oblique manner, Elgar hints there is a secret message enciphered by the Enigma Theme.

A compulsion for cryptography is a reigning facet of Elgar’s psychological profile. A decade of systematic analysis of the Enigma Variations has netted over a hundred cryptograms in diverse formats that encode a set of mutually consistent and complementary solutions. Although this figure may seem astronomical, it is entirely consistent with Elgar’s fascination for ciphers. More significantly, their solutions provide definitive answers to the core questions posed by the Enigma Variations. What is the secret melody to which the Enigma Theme is a counterpoint and serves as the melodic foundation for the ensuing movements? Answer: Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by the German protestant reformer Martin Luther. What is Elgar’s “dark saying” concealed within the Enigma Theme? Answer: A musical Polybius cipher situated in the opening six bars. Who is the secret friend and inspiration behind Variation XIII? Answer: Jesus Christ, the Savior of Elgar’s Roman Catholic faith.

The initials of Elgar’s secret friend are transparently encoded by the Roman numerals of Variation XIII using an elementary number-to-letter key (1 = A, 2 = B, 3 = C, etc.). “X” is the Roman numeral for ten. The tenth letter of the alphabet is J. “III” represents three, and the third letter is C. This cryptanalysis shows that the Roman numerals XIII are a coded form of “JC,” the initials for Jesus Christ. This is not an isolated instance of this encipherment technique in the Enigma Variations. Elgar uses the same number-to-letter key to encode August Jaeger’s initials in Variation IX (Nimrod). “I” is the Roman numeral for one. The first letter of the alphabet is A. “X” stands for ten, and the tenth letter is J.

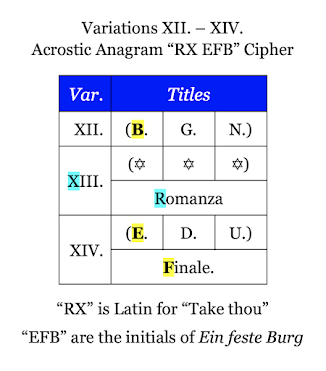

With the secret friend’s initials thinly disguised by the Roman numerals of Variation XIII, what could be the significance of its cryptic title consisting of three hexagrammatic asterisks (✡ ✡ ✡)? That question was resolved in July 2013 by the discovery of the Letters Cluster Cipher, a cryptogram that reveals the three asterisks represent the initials of Elgar’s mysterious missing melody. Those absent initials are encoded by the first letters from the titles of the adjoining movements: Variations XII (B.G.N.) and XIV (E. D. U., and Finale). These first letters are an acrostic anagram of “EFB,” the initials for Ein Feste Burg. Elgar deftly frames the question posed by the three asterisks with the answer hidden in plain sight. This is one of many instances of Elgar encoding information using proximate title letters.

Elgar’s sketches document five lists of the movements for the Enigma Variations. The discovery of the Letters Cluster Cipher verifies that these divergent lists were generated to construct that particular cryptogram. This prospect eluded scholars like Julian Rushton who naively insist Elgar lacked the time to construct any ciphers. Rushton’s speculative rush to judgment is unsupported by the known timeline. Elgar began composing the Enigma Variations in earnest on October 21, 1898. The orchestration was completed on February 19, 1899. From inception to completion, the process consumed 121 days or four months. Such a lengthy period afforded more than ample time and opportunity for Elgar to indulge his passion for cryptography.

By proffering the false supposition that there was insufficient time for Elgar to devise any cryptograms within the Enigma Variations, scholars like Julian Rushton relieve themselves of the obligation to mount a systematic search for ciphers. The inevitable result is an absence of evidence that is myopically misconstrued as proof that there are no ciphers to detect or decrypt. The decision to preemptively rule out the possibility that Elgar incorporated ciphers in the Enigma Variations is a transparent case of confirmation bias.

The acrostic anagram “EFB” from the titles of Variations XII and XIV that encodes the initials of Ein feste Burg is an elementary cryptogram called the Letters Cluster Cipher. Its discovery precipitated a broader analysis of the Enigma Variations’ titles with the goal of uncovering other meaningful and relevant groupings of proximate title letters. This approach is markedly dissimilar from Stephen Pickett’s surgical cherry-picking of single initials from titles and names to assemble a purported solution for the absent Theme. My investigation uncovered words linked to the absent Principal Theme, the Enigma’s “dark saying,” and the secret friend. The Letters Cluster Cipher proved to be the tip of a much larger iceberg of coded information. This assessment uncovered thirty-six cryptograms embedded within the titles of the Enigma Variations. One of the most sophisticated is formed by title letters from the opening four movements and encodes “PIE CHRISTI ABIDE” (Pious Christ Abide).

The “RX EFB” Anagram Cipher

Further analysis identified the acrostic anagram “RX” in the title of Variation XIII. As the ensuing discussion will show, the context of this “RX” anagram cipher presents stunning ramifications about Elgar’s prescription of Ein feste Burg as the covert Theme and its unusual contrapuntal treatment.

Rx is the transliteration of ℞, a pharmaceutical symbol used by physicians and pharmacists for medical prescriptions. The right leg of the capital R is crossed to indicate it is an abbreviation of the Latin verb recipe (“take thou”). Rx first appeared in 16th century manuscripts. Copious examples abound in Dr. William Salmon's book Pharmacopœia Bateana published in London in 1720. Dr. Otto Augustus Wall documents the origin and use of the Rx symbol for medical prescriptions in his 1890 book The Prescription. His textbook affirms that doctors and pharmacists used the Rx abbreviation for medical prescriptions in the 1890s when Elgar composed the Enigma Variations. As a therapeutic or corrective agent, a prescription is a remedy for a particular ailment. In this context, Elgar’s prescription identifies the melodic remedy for his contrapuntal malady.

The merger of the title letters anagrams “RX” and “EFB” from the concluding three movements of the Enigma Variations produce the larger anagram “RX EFB.” As previously noted, “RX” means “take thou.” “EFB” is the initials for Ein feste Burg. Based on this interpretation, “RX EFB” may be read as the statement “Take thou Ein feste Burg.” Elgar’s prescription for solving the enigma of the absent principal Theme is ingeniously encoded by an acrostic anagram drawn from the sequential titles of Variations XII, XIII, and XIV. Like the majority of the titles from the Enigma Variations, the solution consists of varying sets of initials.

The association of “RX” with the absent Theme’s initials “EFB” cleverly hints that the composer of the absent Theme was a doctor. A prescription is issued by a doctor, a title awarded to Luther who was routinely addressed in conversation and official correspondence as “Dr. Martin Luther.” In a stunning parallel, a string of letters threaded through the titles of Variations II through VIII spells out “DR MARTIN” with the last name absent. None of the titles use the capital letter L, precluding the possibility of encoding Luther. The initials “DR” are obtained from Variations II (H. D. S-P.) and III (R. B. T.). The letters for “MARTIN” come from Variations IV (W. M. B.), V (R. P. A.), VI, VII (Troyte), and VIII (W. N.). The proximate title anagram “DR MARTIN” is a massive clue about the composer of the hidden melody.

In addition to its application in medicine, Rx is used in astrology as the abbreviation for the Latin word retrogradus meaning backward. Placing Rx after the symbol for a particular planet indicates that it is moving in retrograde motion. An example of this convention appears on page 15 of the 1881 book The Science of the Stars by Alfred J. Pearce published in London. In this illustration, the symbol for Mars is followed by Rx to specify that it is in retrograde.

Elgar hints at an astronomical context for his “RX” cipher by displaying three conspicuous stars in the title of Variation XIII. When the anagram “RX EFB” is reversed as “EFB RX,” it may be decoded as “Ein feste Burg in retrograde.” A melody that is played backward is described as being in retrograde. Prior research determined that Elgar mapped Ein feste Burg backward above the Enigma Theme as a retrograde counterpoint. The acrostic anagram “EFB RX” is verified by the discovery that Elgar plotted the course of Ein feste Burg in reverse “through and over” the Enigma Theme.

In his essay Measure of a Man: Catechizing Elgar’s Catholic Avatars, Charles McGuire confirms that Elgar attended three Roman Catholic schools between 1863 and 1872.

Elgar began his education in 1863 and over the course of the next few years attended three distinctly different types of schools: a Dame school primarily for girls, a mixed school at Spetchley Park; and, from about 1869 to 1872, a school for young gentlemen at Littleton House. All three schools were Catholic, and all three emphasized elements of religion over all other subjects—at least according to the evidence that has survived.

During this period, the Tridentine Mass was recited in Latin. For this reason, students like Elgar were required to study Latin as part of their religious education. As a student of Latin, Elgar was undoubtedly familiar with the Latin terminology associated with the Rx symbol.

Elgar was a voracious reader with a detailed knowledge of subjects through the 18th century. He recounted his reading materials and habits for an interview published by The Strand Magazine in May 1904:

I had the good fortune to be thrown among an unsorted collection of old books. There were books of all kinds, and all distinguished by the characteristic that they were for the most part incomplete. I busied myself for days and weeks arranging them. I picked out the theological books, of which there were a great many, and put them on one side. Then I made a place for the Elizabethan dramatists, the chronicles including Barker’s and Hollinshed’s, besides a tolerable collection of old poets and translations of Voltaire and all sorts of things up to the eighteenth century. Then I began to read. I used to get up at four or five o’clock in the summer and read—every available opportunity found me reading. I read till dark. I finished reading every one of those books—including the theology. The result of that reading has been that people tell me that I know more of life up to the eighteenth century than I do of my own time, and it is probably true.

Elgar’s exposure to a diverse array of literary sources likely acquainted him with the use of the Rx symbol in medicine and astrology.

Summation

Elgar learned the Latin terms associated with the Rx symbol when he studied Latin at three Roman Catholic schools between 1863 and 1872. His extracurricular reading materials and habits would have further exposed him to the use of that symbol in medicine and astrology. Adjacent title letters from the last three movements of the Enigma Variations form the acrostic anagram “RX EFB.” The Rx symbol is an abbreviation of the Latin word recipe (“take thou”) employed by physicians and pharmacists to instruct patients to “take” a particular therapeutic drug or cure. Published records document that this symbol first emerged in the 16th century and entered common usage long before Elgar conceived of the Enigma Variations in 1898-99. The initials “EFB” are those for Ein feste Burg, the covert Theme of the Enigma Variations. Armed with these insights, the acrostic anagram “RX EFB” may be expanded to read as “Take thou Ein feste Burg.” This coded remedy is Elgar’s prescription for resolving or “curing” his contrapuntal conundrum.

Elgar’s pairing of “RX” with the initials “EFB” cleverly implies that the composer of the missing principal Theme was a doctor. The author of Ein feste Burg was addressed as “Dr. Martin Luther” in conversation and letters. Remarkably, contiguous title letters in Variations II through VIII spell out “DR MARTIN” with his last name omitted. This remarkable title letters anagram furnishes a revealing clue about the composer of the absent Theme. As the leader of the German Reformation, Dr. Luther offered many prescriptions for the ills that plagued the Roman Catholic Church.

Rx is also applied in astrology as the abbreviation of retrogradus, the Latin word for retrograde. An astronomical context is implied by Elgar’s use of three stellar asterisks (✡ ✡ ✡) as the nebulous title for Variation XIII. Reshuffling the acrostic anagram “RX EFB” as “EFB RX” permits the remarkable decryption “Ein feste Burg in retrograde.” This solution is affirmed by the discovery that Elgar mapped the covert Theme backward as a retrograde counterpoint above the Enigma Theme. The precision and specificity of these decryptions are absolutely stunning. To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

%22.jpg)

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment