Jesus with the seven stars and seven lampstands. Fall down seven times and stand up eight.

Japanese Proverb

For the righteous falls seven times and rises again,but the wicked stumble in times of calamity.

Proverbs 24:16 ESV

The British composer Edward Elgar composed the Enigma Variations between 1898 and 1899. This symphonic masterpiece was first performed in June 1899 under the baton of Hans Richter. A protégé of Wagner, Richter directed the inaugural performances of major works by his mentor as well as other luminaries like Brahms, Bruckner, and Dvořák. The premiere of the Enigma Variations catapulted Elgar to international acclaim, quashing the indignity of England’s protracted drought of eminent domestic composers since the heyday of Henry Purcell in the latter half of the 17th century. England would no longer be crassly belittled as “Das Land ohne Musik” — the land without music. Britain’s stigma was lifted by Elgar’s Enigma who unleashed a distinctly English soundtrack to usher in the dawn of the Edwardian era, sublime music that is still heard in epic films to the present day.

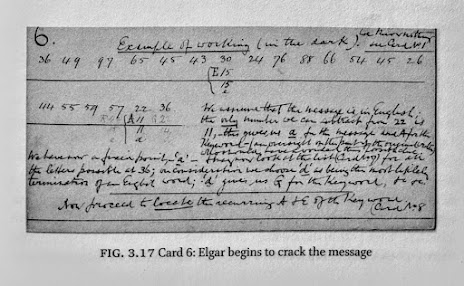

The Enigma Variations pose three ostensibly separate yet overlapping riddles: A covert principal Theme, a “dark saying” lurking within the Enigma Theme, and a secret friend memorialized in Variation XIII. The overarching puzzle centers on the Enigma Theme which is a counterpoint to a famous melody, a subject that has fueled prolonged debate and speculation. For the 1899 program note, Elgar acknowledged the Enigma Theme holds a “dark saying.” The term dark may be defined as something secret or hidden, and a saying is a string of words. While preparing a detailed set of notes laying out how he decoded a supposedly insoluble Nihilist cipher, Elgar wrote, “Example of working (in the dark).”

This appearance of the term dark in reference to a cryptogram bolsters the conclusion that Elgar’s curious phrase “dark saying” is coded language for a cipher ensconced within the Enigma Theme. Finally, Elgar identifies the dedicatees for each of the Variations using their initials, name, or nickname as the title. In place of one of these identifiers for Variation XIII, he placed three hexagrammic asterisks. The identity of Elgar’s secret friend remained a mystery for over a century. A triumvirate of riddles define the mysteries of the Enigma Variations — a covert melody, a coded message, and a confidential friend.

A set of pianola rolls were issued in 1929 by the Aeolian Company to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the Enigma Variations. In anticipation of this release, Elgar prepared a brief series of remarks for each of the movements which were later published by Novello under the title My Friends Pictured Within. His comments for the Enigma Theme include the following arcane statement, “The drop of the seventh in the Theme (bars 3 and 4) should be observed.” This unusual remark prompted Julian Rushton to postulate the correct solution to the Enigma Variations “. . . should take into account the characteristic falling sevenths of bars 3-4.” He opines, “Observed must mean more than merely performed, which might be the case if he had been referring to a dynamic marking . . .” In this context, the definition of observe means to “notice or perceive (something) and register it as being significant.” Based on Elgar’s published statement, there must be some remarkable features of these descending melodic sevenths in bars 3 and 4 that are somehow connected to the enigma.

A synonym for observe is to note. It is telling that Elgar uses the words observed and noted interchangeably in his expository comments. A clear illustration is his remark about Variation X, “The inner sustained phrases at first on the viola and latter on the flute should be noted.” Elgar’s request to observe the falling sevenths is a classic wordplay because they are formed by notes. What he coyly asks his audience to scrutinize are the notes of the descending melodic sevenths. Why would he make such a cryptic reference to the Enigma Theme’s descending sevenths? As a recognized expert in cryptography — the art of encoding and decrypting secret messages — Elgar’s puzzling reference to the falling sevenths in the Enigma Theme hints at the existence of yet another puzzle. His cryptic comment implies there is something to decrypt.

The first falling seventh in bar 3 is a G slurred to an A. These two notes are played by the first violins typically in third position with the G stopped by the fourth finger on the A string, and the A stopped by the second finger on the D string. One string crossing from the A to the D string is executed in bar 3 to complete this inaugural descending seventh. The second falling seventh in bar 4 is an F slurred to a G. The first violins commonly perform this passage in third position with the F stopped by the third finger on the A string, and the G stopped by the first finger on the D string. To play this second seventh, the first violins must cross back from the D to the A string and back again, bringing the total number of string crossings necessary to play both descending sevenths to three. There are many coded allusions to crossing in the Enigma Variations. For instance, the Enigma Theme is set in common time, a time signature that is conducted in a manner that replicates the sign of the cross.

The first pair of descending sevenths occurs in measures 3 and 4. The sum of these bar numbers is seven, a feature that strongly suggests these numbers are associated with the key to decoding this cipher. The first descending seventh occurs on the third beat of measure 3. Such a conjunction of simultaneous threes (33) is undoubtedly a coded reference to Elgar’s initials (EE). He routinely signed his correspondence with his initials in the form of two capitalized cursive Es. These letters are the mirror or reverse image of “33”. It was observed that exactly three string crossings are required to play the descending sevenths in bars 3 and 4. It should also be noted that the word three has “ee”.

There are a variety of cryptograms embedded within the Enigma Variations that Elgar cleverly initialed in some discernible way. Initials are a prevailing feature of the majority of the titles found in the Enigma Variations. Elgar’s coded initials also appear as precisely two E-flats in the accompanying parts of bars 3 and 4. The first E-flat is played by the cellos on the third beat of bar 3 in conjunction with the first descending seventh’s high note (G). The next E-flat is performed by the second violins on the third beat of bar 4 with the lower note (G) of the second falling seventh. It is abundantly apparent that Elgar’s initials bookend the beginning and end of his Falling Sevenths Cipher.

What form of encipherment could he have employed involving the notes of the falling sevenths in bars 3 and 4 of the Enigma Theme? It is relevant to remember that Elgar was immersed in Roman lore during the months leading up to the genesis of the Enigma Variations. In 1897 and 1898, his artistic energies were directed toward completing Caractacus Op. 35. This oratorio recounts the historic drama of a British chieftain who heroically resisted the Roman legions at the British Camp on the Malvern Hills. Although defeated and carted off as a captive to Rome, Caractacus so impressed Claudius, the fourth Emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, that he was graciously pardoned.

|

| Caractacus standing before Ceasar. |

Elgar’s interest in the intersections of Roman and British history extended to Julius Caesar (who mounted two invasions of Britain) and his reliance on cryptography to communicate clandestine orders to his legions and allies. Elgar retained in his personal library a series of four articles published by The Pall Mall Magazine in 1896 under the collective title “Secrets In Cipher.”John Holt Schooling prepared these informative and engaging exposés regarding the history of secret codes. The first installment — “From Ancient Times To Late Elizabethan Days” — provides an incisive description of a cipher used by Julius Caesar. Schooling writes, “. . . the historian Suetonius relates that when Caesar would convey any private business he did usually write it by substituting other letters of the alphabet for those which composed his real meaning — such as D for A, E for B, and so for the rest.” This elementary and widely recognized form of encipherment is known as the Caesar shift. Elgar studied this basic encipherment technique at least two years before turning his attention to completing the Enigma Variations in 1898-99.

The chord played with the G of the first descending seventh in bar 3 of the Enigma Theme is a C minor added sixth chord. The notes of that chord are C, E-flat, G, and A. It is remarkable all the letters in the name Caesar that may be represented by musical notes (Caesar) are present in that particular chord. Notice too that the title Caesar has six letters. In consideration of these facts, it is entirely plausible Elgar applied Caesar’s encipherment method to the notes forming the falling sevenths in measures 3 and 4 of the Enigma Theme. But how many letters should the note letters be shifted, and in which direction? The bar numbers and note order within each descending seventh prove to be the keys. The bar number identifies the size of the shift, and the order of the letters in the corresponding descending seventh designates the course either forward or backward within the musical alphabet which encompasses the first seven letters, A through G.

The first descending seventh in bar 3 begins on G and ends on A. The note A precedes G in the musical alphabet. The placement of the seventh letter before the first in this opening descending seventh indicates a backward course, and the bar number indicates a left shift in the alphabet of three letters. Counting back three letters in the musical alphabet is akin to applying a downward transposition of a third. When this intervallic shift is performed to the notes G and A in bar 3, it produces an E-flat and F respectively in the G minor mode.

The second falling seventh in bar 4 consists of the notes F and G which appear in sequential order. According to the key, this indicates a right shift forward in the musical alphabet with the bar number pinpointing the number of steps. Applying an upward transposition of a fourth to the notes F and A produces B-flat and C in the G minor mode. Stripped of their accidentals, the plaintext solution letters for the four notes of the two descending sevenths in bars 3 and 4 of the Enigma Theme are in order E, F, B, and C. The first three letters supply the initials for the covert Theme in the proper order, Ein feste Burg. The remaining letter C is a phonetic equivalent for the word sea. This particular letter is significant because Elgar quotes fragments from Mendelssohn’s overture Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage in Variation XIII to depict a steamer crossing a calm sea. With the notes of these marine quotations cited over an ostinato played by the violas recapitulating the Enigma Theme’s palindromic rhythm, Elgar deftly encodes the initials for Ein feste Burg via another Caesar shift cipher. In this context, it is incredibly revealing that the first syllable of Caesar’s name is the phonetic equivalent of sea, and the suggestive subtitle for that movement is Romanza.

The decryption of the Enigma Theme Locks Cipher confirms that Elgar applied a number-to-letter key by counting both forward and backward in the musical alphabet. A major benefit of this strategy is to harden the cipher against straightforward decryption. What could be more shifty than for Elgar to shift directions in his application of the Caesar shift cipher?

The note letters of the descending sevenths in measures 3 and 4 are also connected to the English translation of the covert Theme’s complete six-word title, A Mighty Fortress Is Our God. The second lower note (A) forms the first melodic seventh sounds by itself as the rest of the orchestra remains silent. This A is the only note in the descending sevenths that is played without any other accompanying voices. What significance could be attached to this solitary note that sounds alone? One credible explanation is that it implicates the first initial and word in the covert Theme’s title, A Mighty Fortress. Indeed, all four notes from the two descending sevenths are the first, third, and sixth initials from the covert Theme’s complete six-word title, A Mighty Fortress Is Our God. It is salient to observe these are the only initials from that title which may be directly represented by letters from the musical alphabet. The third and sixth initials match the numerals from the opus number (36).

The order of the first falling seventh notes (G to A), hints at placing the end at the beginning, and the beginning at the end. This is the case because G is the last initial from the covert Theme’s complete six-word English title, and A is the first. The application of a reverse Caesar shift in bar 3 to the notes of the descending seventh further reinforces this suspicion which is verified by Elgar’s retrograde counterpoint of Ein feste Burg “through and over” the Enigma Theme. He begins his enigmatic counterpoint with the covert Theme’s last note and phrase and maps the entire melody backward over the Enigma Theme’s ABA’C structure.

The Enigma Theme’s structure is a phonetic spelling of aback, a term that is defined as “backward” or “taken by surprise.” A retrograde counterpoint is both backward and surprising to those who expect the hidden melody would commence from its first note and phrase at the beginning. No wonder Elgar gave the opening Theme the title Enigma.

The chords performed with the descending sevenths by the remaining three voices of the string quartet are remarkable because they feature at their extremities the notes E-flat, F, and B. The E-flat appears on beat 3 of bar 3, and the F and B on beats 1 through 2 of bar 4. These note letters appear concurrently in the same narrow section of the score as the Falling Sevenths Cipher.

Elgar’s flexible treatment of a capital cursive E to construct various glyphs for his Dorabella Cipher demonstrates a willingness to reorient letters to resemble other meaningful symbols. Simply by changing the angle of a capital cursive E produces such varying outcomes as the letter M and the number 3.

This realization invites another plausible explanation for Elgar’s conspicuous reference to the Enigma Theme’s falling sevenths. When the number 7 literally falls, the inverted mirror image closely resembles a capital L. This phenomenon is easily visible on a playing card.

The rhythm of the descending sevenths in the Enigma Theme is comprised of two quarter notes. This pattern is the equivalent of two dashes in Morse Code which encodes the letter M. When the Morse Code translation of the falling seventh’s rhythm is paired with an inverted 7, it produces ML. These two letters are the initials of Martin Luther, the composer of Ein feste Burg. This conclusion is reinforced by Elgar’s identification of the earliest sketch of Variation XIII with a solitary capital L. Only later did he append the letters “ML”, the initials for Martin Luther. In all, there are three interrelated sets of initials encoded by the Falling Sevenths Cipher. Two pertain to the German and English titles of the covert Theme, and a third to its composer.

The melodic intervals immediately preceding the falling sevenths in bars 3 and 4 of the Enigma Theme are a rising perfect 4th (D to G), and an ascending minor 6th (A to F). These two numbers are noteworthy because they may be merged to produce 46, the precise chapter from the Psalms that in its first line supplies the title of the covert Theme. The first letters of the performance directions from the Enigma Theme’s opening bar are an acrostic anagram for “EE’s PSALM”. These may be linked to the falling sevenths since there are precisely seven performance directions. The notes of the perfect 4th (D and G) preceding the first descending seventh are a reverse phonetic spelling of God, the final word of the covert Theme’s title. A central doctrine of Roman Catholicism is the belief that Jesus is one of three coeternal consubstantial persons that encompass the Triune God. It is far from arbitrary that Variation XIII begins with the melody notes G and D, its Roman numerals are a transparent number-to-letter cipher encoding the secret friend’s initials (JC), and the asterisks on the original sketch and published score are hexagram — the Star of David. Two descending sevenths suggest the number 77. According to the Gospel of Luke, Jesus was the 77th generation from Adam. Multiple lines of evidence converge to confirm that Jesus is the secret friend memorialized in Variation XIII.

Extensive research and analysis confirm the elusive secret melody to the Enigma Variations is the famous hymn Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by the German Reformation leader Martin Luther. This was an unexpected discovery as Elgar was raised a devout Roman Catholic, a trait outwardly at odds with Luther who was proclaimed a heretic and excommunicated by Pope Leo X. Elgar was a committed disciple of the German School, an enclave of eminent composers who all share one conspicuous theme. Although Bach, Mendelssohn, and Wagner wrote in dramatically divergent styles and genres, they reverently quote Luther’s most popular hymn in their music. Elgar followed in the hallowed footsteps of his musical forebears, yet did so surreptitiously to avert open conflict with his proud Roman Catholic faith. No wonder he kept his secret with such devout resilience, particularly during and after World War I when anything remotely German was despised and ostracized from his beloved England.

An intricate Music Box Cipher situated in the opening six measures of the Enigma Theme encodes the complete 24-letter 6-word German title of the covert Theme in the form of a grand anagram. For example, the plaintext solution for bar 1 is “GSUS”, a phonetic spelling of Jesus, the name of the secret friend memorialized in Variation XIII. Elgar’s brilliant reshuffling of the letters produces meaningful and relevant phrases and words spelled out phonetically in Latin, English, and what he reasonably believed to be Aramaic based on contemporaneous biblical commentaries in widespread use.

In an astonishing display of cryptographic counterpoint, Elgar spells his last name in the form of an acrostic anagram utilizing the four languages revealed by the decryption: English, Latin, German, and Aramaic. He autographed his secret message using a second cipher only unveiled by the correct solution of the larger cryptogram. Elgar’s coded signature authenticates the decryption and verifies he dutifully recorded the correct answers to his Enigma Variations within the body of the full score. The catch was he wrote down the solutions in cryptograms for posterity to eventually detect and decipher. To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

No comments:

Post a Comment