Elgar was an ardent Wagnerian whose interest in Liszt was undoubtedly fueled by his intimate friendship with that revolutionary German composer. In 1854, Liszt sent

Richard Wagner (1813–1883) some music written to commemorate the 100th birthday of the famous German poet and playwright

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832). Wagner

replied, “I compare it to the claw by which I recognise the lion; but now I call out to you, Show us the complete lion…”[11] Wagner likened the music of Liszt to a lion likely as a wordplay on Lyon. Liszt received many titles and honors. One of his most notable titles was the Cross of the Lion of Belgium conferred on July 18, 1842.[12] The association between Liszt and the lion is so prevalent that musicologist

Alan Walker calls Liszt “

The Lion of Weimar.”[13]

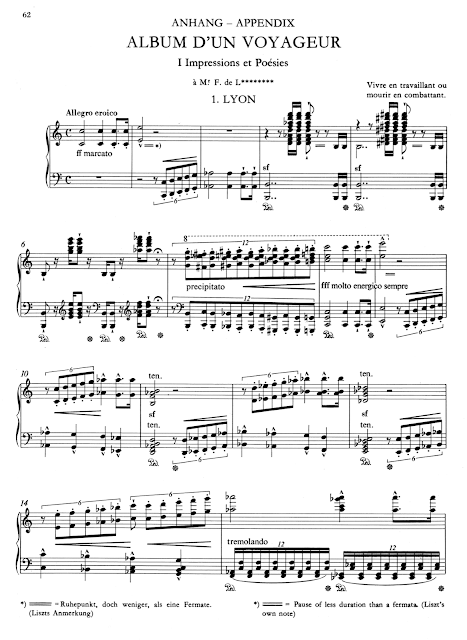

Liszt dedicated his composition Lyon to "M. F. de L." The first two letters of the plaintext description of the Caesar shifts are M and L. The ciphertext for the plaintext M is F, the remaining initial in Liszt's dedication. Consequently, all three initials from Liszt's dedication (MFL) are recorded by the original plaintext (6) and Caesar shift plaintext (12, 11) in conjunction with a phonetic spelling of Lyon. Such an uncanny combination reeks of intelligent design.

The seventh and eighth letters are

I/

J and

P. Elgar was fond of practical jokes that he called japes. When treated as a noun, a

jape is defined as “something designed to arouse amusement or laughter.” When used as a verb, jape means “to say or do something jokingly or mockingly.”[14] Elgar’s correspondence bristles with inventive phonetic or trick spellings. For example, he respelled “excuse” as “xqqq.” Other exemplars of Elgar’s creative spellings are listed below:

- Bizziness (business)

- çkor (score)

- cszquōrrr (score)

- fagotten (forgotten)

- FAX (facts)

- frazes (phrases)

- gorjus (gorgeous)

- phatten (fatten)

- skorh (score)

- SSCZOWOUGHOHR (score)

The realization that Elgar was an enthusiast for unconventional spellings permits a reading of the adjacent letters “JP” as a phonetic rendering of

jape. The inclusion of the “I” permits a phonetic reading of “I JP” as “I jape.” The Liszt fragment cipher encodes a wry jape in Elgar’s native language. In commenting about another more famous cipher by Elgar that employs the same characters found in the Liszt fragment, Bauer

suspects “. . . the reason the automated programs fail to break the Dorabella cipher is because much of it consists of misspelled words and words invented by Elgar . . .”[15] Consistent with Bauer’s hunch, Elgar deploys some phonetic misspellings in his Liszt fragment password key.

The ninth, tenth, and eleventh letters are “RHP.” The letter “R” is a homonym of “Our.” The letters “HP” form a phonetic spelling of “Hope.” The plaintext cluster “RHP” may be interpolated as “Our Hope.” The final seven plaintext letters are “KAAFAAA.” This plaintext series is a phonetic rendering of the German word “

Kaffee” that translates as

coffee. Remarkably, the last two letters in the correct German spelling “Kaffee” furnish Elgar’s initials (EE). The German poet

Heinrich Heine (1797–1856) coined the term “

Lisztomania” to describe how young women venerated Liszt by vying for his discarded gloves, plucking hairs from his head as keepsakes, retrieving his cigar butts and secreting them away in their corsets, and saving the dregs from his

coffee cups in small vials.[16] There is an unmistakable comical connection between Liszt, coffee, and his adoring fans.

Siegfried Wagner

recalled an amusing coffee prank perpetrated by Liszt at a dinner party hosted by an aristocratic matron. When served coffee, Liszt helped himself to a domino of sugar using his fingers rather than the sugar-tong. Repulsed by Liszt’s unsanitary table manners, the Madame ordered the butler to immediately empty the sugar bowl out the window and refill it. Nonplussed, Liszt quietly finished his coffee, proceeded to the same window, and tossed his cup outside. When the Madame protested, Liszt politely replied, “If Madame would throw the sugar out because my fingers had touched it, she surely would not drink again from a cup my lips had touched.”[17]

Only one French term and one English word are spelled correctly in this password key with the remaining English and German words realized phonetically. As amply testified to by his correspondence, phonetic spellings bear Elgar's cryptographic fingerprints. The password key that encodes the Caesar shifts is written as “M LYOUN I/JP RHP KAAFAAA.” Remarkably, these letters appear in this precise order within the key. The phonetic translation of this password key reads, “M(F) LYOUN, I JAPE OUR HOPE COFFEE.” There are two French elements, four English terms, and one German word. Three languages are employed in this password key:

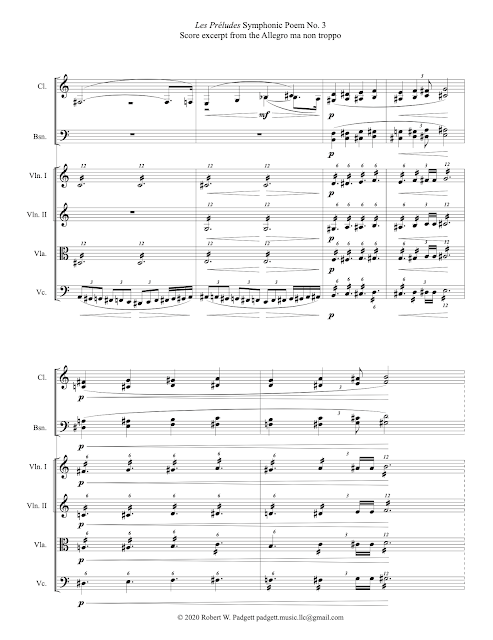

The use of multiple languages with some phonetic spellings hardens this keyword cipher against decryption. The sum of these languages is reflected by the number three assigned to Les Préludes. The choice of languages reflects the lingua franca of Liszt (French and German) and Elgar (English). In his youth, Elgar studied the German language because he dreamed of attending the Leipzig Conservatory, Germany's oldest university school of music. The notes of the recurring motive performed by the cellos in the fourth bar of the

Allegro ma non troppo are G-sharp, F, and E. Those three note letters conveniently furnish the initials for those three languages: German, French, and English. The cellos perform those same pitches in the first two bars of this section with the G-sharp respelled enharmonically as A-flat.

A Ringing Endorsement

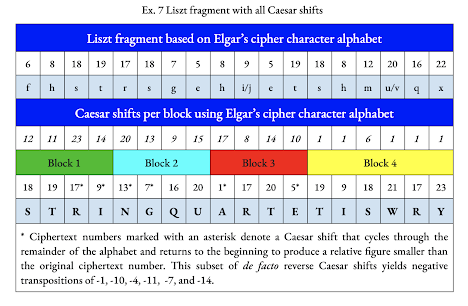

Ciphertext numbers marked with an asterisk indicate a Caesar shift that cycles through the entire alphabet and returns to the beginning to produce a relative figure smaller than the original ciphertext number. For example, a ciphertext number of 18 (S) subject to a Caesar shift of 23 adds up to 41, a sum greater than the 24 characters in Elgar’s cipher alphabet. The shift from the first letter of the alphabet is the difference of 41 less 24 which yields 17 (R). This would be the equivalent of a Caesar shift of -1, a step backward by one letter. A total of six Caesar shifts circle back to the beginning of the alphabet with two in each of the first three blocks. The consistent distribution of two de facto negative Caesar shifts in the first three blocks indicates deliberation and design.

In all, six of the eighteen plaintext letters in the Liszt fragment are encoded by negative Caesar shifts. These reverse Caesar shifts (-1, -10, -4, -11, -7, -14) apply to ciphertext letters in positions 3-6, 9 and 12. Six of eighteen letters constitute 33 percent of this cryptogram. The number 33 is the mirror image of Elgar’s initials consisting of two cursive capital Es. Such a precise percentage mathematically implies a coded version of Elgar’s initials.

Further analysis revealed that this set of negative Caesar shifts constitutes a sub-cipher within the password key. In order of appearance, the plaintext for the first four reverse Caesar shifts spells “RING.” The orchestral score of Les Préludes No. 3 includes “Becken,” the German name for cymbals. That percussion instrument produces a loud crash followed by a sustained ring that may be dampened by placing the cymbals’ edges against the performer’s chest. Liszt’s scoring in the concluding Andante maestoso does not call for dampening the cymbals, permitting them to ring out above the orchestra.

The word “RING” is also closely associated with Richard Wagner (1813–1883) and his colossal opera cycle

Der Ring des Nibelungen (

The Ring of the Nibelung). Referred to simply as the Ring, Wagner composed this series of four operas that require approximately 15 hours to perform. Liszt was an early and generous supporter of Wagner, a romantic composer whose music exerted a profound and lasting influence on Elgar. Elgar’s absorption and distillations of leitmotifs from Wagner’s operas are widely acknowledged in his compositions. Wagner effusively praised Liszat’s invaluable assistance following the August 1876 premiere of the Ring at Bayreuth, a unique opera house and shrine explicitly built for Wagner’s

Gesamtkunstwerk (Total artwork). Wagner

toasted Liszt in these words:

For everything I am and have achieved I have one man to thank, without whom not a single note of mine would be known, a dear friend who, when I was banned from Germany, with incomparable devotion and self-sacrifice drew me to the light and first recognized me. To this dear friend is due the highest honour. It is my noble friend and master, Franz Liszt![18]

The first four plaintext letters revealed by negative Caesar shifts spell “RING” and allude to Liszt’s intimate connection to Wagner’s extraordinary opera cycle. There are four operas in the Ring, and likewise, there are four blocks in Elgar’s cipher. A consideration of the remaining two plaintext letters produced by negative Caesar shifts (A and E) with the original four letters is the anagram “A RING - E.” This may be read as “A RING” with Elgar’s initial appended at the end.

Negative Caesar Shifts (-1, -10, -4, -11, -7, -14) apply to ciphertext letters in positions 3-6, 9 and 12 of the Liszt fragment. The application of a number-to-letter key (1 = A, 2 = B, 3 = C, etc.) to those letter positions using Elgar’s cipher alphabet yields C, D, E, F, I/J, and M. The sequential application of the negative Caesar shifts (-1, -10, -4, -11, -7, -14) to those letters produces B, S, A T, B, and X. That assortment of letters is an anagram of “BXSTAB,” a phonetic rendering of “Backstab.” Two principal characters from Wagner’s Ring cycle are Brunhilde and Siegfried. Brunhilde uses a magic potion to protect every part of Siegfried’s body except for the small of his back. In

Act III of

Gӧtterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods), the fourth and final opera in the Ring cycle, Siegfried is murdered when Hagen stabs him in the back with a spear. This ancillary cryptogram intersects elegantly with the encoding of “RING” by the negative Caesar shifts. Like Siegfried, Caesar was stabbed to death by rivals whom he mistakenly believed were trusted

allies.Summation

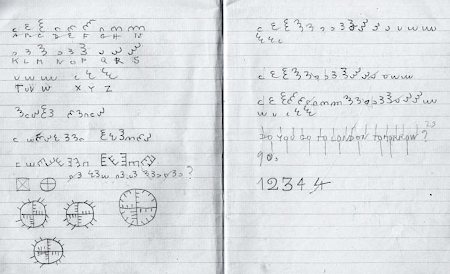

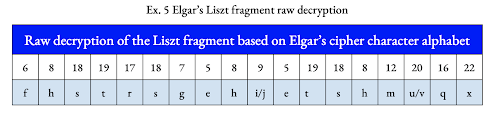

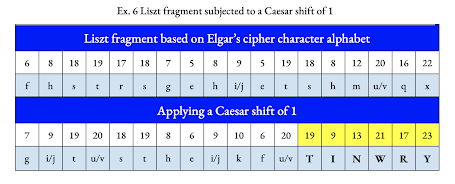

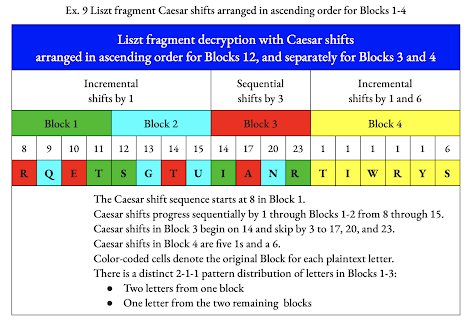

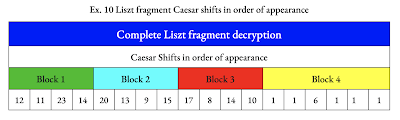

The efficiency and multilayering of the Liszt fragment ciphers present an impressive demonstration of Elgar’s cryptographic prowess. With three characters oriented at diverse angles, he efficiently generates 24 symbols that replace the English alphabet’s 26 letters by conflating the letters i/j and u/v. These curlicue symbols are the first layer of encryption. Liszt’s longstanding reputation as a musical “Caesar” fueled the suspicion that Elgar deployed a Caesar shift system to construct his enigmatic fragment. Brute-forcing the cipher revealed its eighteen characters encode the phrase “STRING QUARTET IS WRY.” The decryption draws on a combination of thirteen different Caesar shifts within four blocks, three with four letters and one with six. Thirteen different Caesar shifts form the second encryption layer.

The Liszt fragment is penciled next to the program note that discusses the Allegro ma non troppo section of Les Préludes No. 3. The orchestration of that passage is dominated by the string quartet with the cellos playing rapid chromatic runs below energetic tremolos that crescendo and decrescendo in the upper strings. The phrase “STRING QUARTET IS WRY” is an apt characterization of this passage, rendering this decryption of the Liszt fragment as contextually accurate and appropriate.

Viewing the decryption through the lens of Elgar’s musical expertise permits a deeper appreciation of his cryptogram’s ingenious construction. Four blocks and their respective complement of letters mirror the number of instruments and their relative sizes within a string quartet. Blocks 1 through 3 share an equal complement of four letters, and Block 4 has six. A string quartet consists of two violins, one viola, and one cello. The violin and viola are nearly identical in size, but the cello is much larger. Like the 2-1-1 distribution of the instruments in a string quartet, Elgar’s Caesar shifts are distributed in a 2-1-1 pattern within Blocks 1-3 where two are drawn from one Block and two from the remaining Blocks.

The mechanism of Elgar’s cryptogram relies on a series of thirteen different Caesar shifts. Although many Caesar shifts may appear random, an in-depth analysis reveals they are distributed in a sophisticated pattern that suggests a passphrase key. When converted into their respective letters from Elgar’s cipher alphabet, they produce a series of recognizable words and phrases in French, English, and German. The passphrase key begins with “M” followed by “LYOUN,” the old French spelling of Lyon. Liszt’s well-known piano piece Lyon is dedicated to “M.F. de L.” The plaintext letter M corresponds with the ciphertext F (the second initial of the dedication), and the third initial (L) overlaps with the spelling of “LYOUN.” This first part of the cipher key consists of two parts in French, Liszt’s preferred conversational language.

The second part of the passphrase key is “I/JP.” The letter “I” is the first person pronoun that refers to Elgar. The letters “JP” are a phonetic adaption of “Jape.” Elgar orchestrated practical jokes that he called “japes.” The letters “I/JP” is a phonetic version of the phrase “I jape” that conveys Elgar’s known proclivity for pranks and mockery. The Liszt fragment encodes a wry remark about the orchestration of the Allegro ma non troppo, constituting a concealed jape.

The third part of the passphrase key is “RHP”. The letter “R” is a phonetic version of “Our.” The letters “HP” are a phonetic rendering of “Hope.” The letters “RHP” produces a phonetic rendition of the phrase “Our Hope.” The fourth and final part of the password key is “KAAFAA.” This is a phonetic spelling of Kaffee, the German word for coffee. Remarkably, the last two letters in that German term replicate Elgar’s initials. The letters “I/JP R HP KAAFAA” generate the phrase “I jape our hope coffee.” These phonetic words reflect Elgar’s affinity for unconventional spellings, a cunning tactic to thwart cryptanalysis. Liszt spoke French and German. Elgar’s native language was English, but he also learned to read, write, and speak German. These linguistic links to Liszt and Elgar bolster the efficacy of this secondary password key that furnishes a third tier of encryption.

There are six Caesar shifts in the Liszt fragment cipher that “wrap around” the alphabet and replace ciphertext with plaintext appearing earlier in the alphabet. The first four of these reverse Caesar shifts occur consecutively in the 3rd through 6th positions and spell “RING.” Liszt is closely associated with Wagner’s famous Ring Cycle. When “RING” is contemplated with the remaining plaintext letters for the remaining two negative Caesar shifts in the 9th (A) and 12th (E) positions, it permits the anagram “A RING - E.” This may be read as the phrase “A RING” followed by Elgar’s initial. This cipher within the decryption presents a fourth layer of encryption.

Ciphertext letters in positions 3-6, 9, and 12 of the Liszt fragment are subjected to effective negative Caesar shifts of -1, -10, -4, -11, -7, and -14. The application of a number-to-letter key to those letter positions using Elgar’s cipher alphabet yields C, D, E, F, I/J, and M. The application of the negative Caesar shifts (-1, -10, -4, -11, -7, -14) in sequence to those ciphertext letters produces B, S, A T, B, and X. That assortment of letters is an anagram of “BXSTAB,” a phonetic rendering of “Backstab.” In Act III of Gӧtterdämmerung, Hagen assassinates Siegfried by stabbing him in the back with a spear. This fifth layer of encryption elides elegantly with the “RING” sub-cipher associated with the negative Caesar shifts. Like Siegfried, Caesar was betrayed by poseurs feigning to be allies and bludgeoned to death.

Elgar’s Liszt fragment has resisted all attempts at a solution for 135 years. Now the reasons for its resilience are manifest. Its mechanism is coyly suggested by the construction of its characters from the lowercase “c” shifted into contrasting configurations, for that letter is the initial for Caesar. The Liszt fragment is a sophisticated multilayered, multidisciplinary, and multilingual Vigenère cipher that enciphers a narrow band of consistent and mutually supportive solutions. Both Liszt's reputation as a musical “Caesar” and his music furnish critical clues for unlocking Elgar's earliest known cryptogram. It is extraordinary how much information was efficiently encoded within these eighteen enigmatic characters.

Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

About the Authors

Wayne Packwood

Mr. Packwood attended Binley Park Coventry school before joining the Army. After serving in the Army for four years, he joined the Electrical Engineering firm Lee Beasley where he was employed for a decade. During his tenure at Lee Beasley, he became a qualified Electrical Engineer by completing coursework and training through the Joint Industry Board of Electrical Engineers. He next joined AT&T as a Project Manager where he was promoted to middle management and supervised a team of 19. Mr. Packwood is self-taught in the discipline of cryptography. His original research was published in the July 2020 issue of the journal Musical Opinion. A member of the Elgar Society, he presently serves as a carrier with Royal Mail.

Robert W. Padgett

Mr. Padgett graduated from Vassar College Phi Beta Kappa and Magna Cum Laude with a degree in Psychology. He has performed on the violin for Prince Charles, Lady Camilla, Steve Jobs, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Maria Shriver, Gavin Newsom, George Shultz, William F. Buckley, Jr., Van Cliburn, Joseph Silverstein, Marcia Davenport, and other public figures. His original compositions have been performed by the Monterey Symphony, at the Bohemian Grove, the Bohemian Club, and other private and public venues. In 2008, Mr. Padgett won the Max Bragado-Darman Fanfare Competition with his entry Fanfare for the Eagles. It was premiered by the Monterey Symphony under Maestro Bragado-Darman in May 2008. Mr. Padgett is a member of the Elgar Society and has presented papers at annual conferences. Married with five children, he resides in Plano, Texas, where he teaches violin, viola, piano, music theory, and composition.

No comments:

Post a Comment