With the sign of the Cross, I shall more certainly break through the ranks of the enemy than if armed with shield and sword.

St. Martin of Tours (316 or 336—397)

The late romantic composer Edward Elgar excelled in cryptography, the science of coding and decoding secret messages. His obsession with that esoteric discipline merits an entire chapter in Craig P. Bauer’s book Unsolved! Bauer devotes much of the third chapter to Elgar’s meticulous decryption of an allegedly insoluble Nihilist cipher presented by John Holt Schooling in the April 1896 issue of The Pall Mall Magazine. A Nihilist cipher is built on a Polybius square key. Elgar was so gratified by his solution to Schooling’s purportedly impenetrable code that he specifically mentions it in his first biography released by Robert J. Buckley in 1905.

Elgar painted his decryption in black paint on a wooden box, an appropriate medium considering that another name for the Polybius square is a box cipher. His process for cracking Schooling’s cryptogram is summarized on a set of nine index cards. On the sixth card, Elgar likens the task to “. . . working (in the dark).” It is significant that he used the word “dark” as a synonym for cipher.

This parenthetical remark is revealing as he employs that same language in the original 1899 program note to characterize his eponymous Enigma Theme. It is an oft-cited passage that deserves revisiting as Elgar lays the groundwork for his tripartite riddle:

The Enigma I will not explain – its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’, but is not played . . . So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some later dramas – e.g., Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’ – the chief character is never on the stage.

Elgar uses the words dark and secret interchangeably in a letter to August Jaeger penned on February 5, 1900. He wrote, “Well—I can’t help it but I hate continually saying ‘Keep it dark’—‘a dead secret’—& so forth.” One of the definitions for dark is “secret,” and a saying is a series of words that form a coherent phrase or adage. Elgar’s odd expression — “dark saying” — is coded language for a cipher. In an oblique manner, Elgar hints there is a secret message enciphered by the Enigma Theme.

Mainstream scholars speculate that the Enigma Variations have no answer because Elgar allegedly concocted the notion of an absent principal Theme as an afterthought, practical joke, or marketing gimmick. The editors of the Elgar Complete Edition casually deny the likelihood of any covert counterpoints or cryptograms. Relying on Elgar’s recollection of playing new material at the piano to gauge his wife’s reaction, they tout the standard lore that he must have extemporized the idiosyncratic Enigma Theme mirabelle dictu without any forethought or planning:

There seems to have been no specific ‘enigma’ in mind at the outset: Elgar’s first playing of the music was hardly more than a running over the keys to aid relaxation. It was Alice Elgar’s interruption, apparently, that called him to attention and helped to identify the phrases which were to become the ‘Enigma’ theme. This suggests it is unlikely that the theme should conceal some counterpoint or cipher needed to solve the ‘Enigma’.

Such a blanket renunciation conveniently relieves scholars of any obligation to probe for ciphers. The huge irony is proponents of that myopic denialism extol the validity of their position based on a dearth of evidence for which they never executed a diligent or impartial search. Such a ridiculous state of affairs is a textbook case of confirmation bias pawned off as “scholarship.”

A more sensible view embraced by those who take Elgar at his published word accepts the challenge that there is a famous melody lurking behind the Variations’ contrapuntal and modal facade. In his 1905 biograph, Elgar plainly states, “The theme is a counterpoint on some well-known melody which is never heard . . .” Most scholars insist the answer can never be known because Elgar allegedly took his secret to the grave. This rigid absolutism presumes he never wrote down the solution for posterity to discover. Such a rigid opinion glosses over or blatantly ignores Elgar’s documented obsession with cryptography. That incontestable facet of his psychological profile accentuates the prospect that the solution is skillfully encoded within the orchestral score of the Enigma Variations.

A compulsion for cryptography is a reigning facet of Elgar’s psychological profile. A decade of systematic analysis of the Enigma Variations has netted over a hundred cryptograms in diverse formats that encode a set of mutually consistent and complementary solutions. Although this figure may seem astronomical, it is entirely consistent with Elgar’s fascination for ciphers. More significantly, their solutions provide definitive answers to the core questions posed by the Enigma Variations. What is the secret melody to which the Enigma Theme is a counterpoint and serves as the melodic foundation for the ensuing movements? Answer: Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by the German protestant reformer Martin Luther. What is Elgar’s “dark saying” concealed within the Enigma Theme? Answer: A musical Polybius cipher situated in the opening six bars. Who is the secret friend and inspiration behind Variation XIII? Answer: Jesus Christ, the Savior of Elgar’s Roman Catholic faith.

The initials of Elgar’s secret friend are transparently encoded by the Roman numerals of Variation XIII using an elementary number-to-letter key (1 = A, 2 = B, 3 = C, etc.). “X” is the Roman numeral for ten; the tenth letter of the alphabet is J. “III” represents three; the third letter is C. This cryptanalysis shows that the Roman numerals XIII is a coded form of “JC,” the initials for Jesus Christ. This is not an isolated instance of this encipherment technique in the Enigma Variations. Elgar uses the same number-to-letter key to encode August Jaeger’s initials in Variation IX (Nimrod). “I” is the Roman numeral for one. The first letter of the alphabet is A. “X” stands for ten, and the tenth letter is J.

With the secret friend’s initials thinly disguised by the Roman numerals of Variation XIII, what could be the significance of its cryptic title consisting of three hexagrammatic asterisks (✡ ✡ ✡)? That question was resolved in July 2013 by the discovery of the Letters Cluster Cipher. That cryptogram divulges that the three asterisks signify the initials of Elgar’s mysterious missing melody. The absent letters are encoded by the first letters from the titles of the adjoining movements: Variations XII (B. G. N.) and XIV (E. D. U., and Finale). The letters are an acrostic anagram of “EFB” — the initials of Ein Feste Burg. Elgar deftly frames the question posed by the three asterisks with the answer hidden in plain view. This is one of many instances where Elgar encodes information as anagrams using proximate title letters.

Elgar produced five lists of the fifteen movements from the Enigma Variations. The discovery of the Letters Cluster Cipher shows that these divergent lists were generated to construct that specific cryptogram. The prospect of cryptograms eluded scholars like Julian Rushton who naively insist Elgar lacked the time to construct any ciphers. Rushton’s speculative rush to judgment is unsupported by the known timeline. Elgar began composing the Enigma Variations in earnest on October 21, 1898. The orchestration was completed on February 19, 1899. From inception to completion, the process consumed 122 days. In addition, Elgar appended 96 bars to the Finale between June 30 and July 20, 1899, adding 21 more days for a grand total of 143 days. Such a lengthy period of time afforded ample opportunity for Elgar to indulge his passion for cryptography. The appraisal of legacy scholars such as Julian Rushton is demonstrably fallacious.

By proffering the false presumption that there was inadequate time for Elgar to craft and insert cryptograms within the Enigma Variations, scholars carelessly relieve themselves of any obligation to mount a systematic search for ciphers. The inevitable result is a dearth of evidence that is myopically misconstrued as proof that there are no ciphers to detect or decrypt. The decision to preemptively rule out the possibility that Elgar may have embedded ciphers in the Enigma Variations is a brazen case of confirmation bias passed off as “scholarship.”

The cryptogram that encodes the initials of Ein feste Burg in the titles of Variations XII and XIV is called the Letters Cluster Cipher. Its discovery precipitated a broader analysis of the Enigma Variations’ titles with the goal of uncovering other meaningful and relevant groupings of proximate title letters. This approach is markedly dissimilar from Stephen Pickett’s surgical cherry-picking of single initials from titles and names to assemble a purported solution for the absent Theme. My investigation uncovered words linked to the absent Principal Theme, the Enigma’s “dark saying,” and the secret friend. The Letters Cluster Cipher proved to be the tip of a much larger iceberg of enciphered information consisting of over thirty-six cryptograms embedded within the titles of the Enigma Variations. One of the most elaborate encodes the anagram “PIE CHRISTI ABIDE” (Pious Christ Abide) using adjacent title letters from the opening four movements.

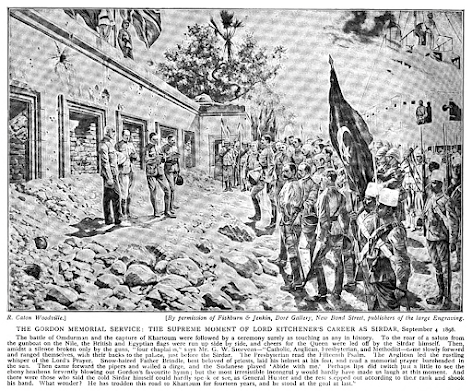

“Pie” is the Latin word for pious. “Christi” is the Latin translation of Christ. Elgar used the Latin word Christi in the title of his first sacred oratorio, The Light of Life (Lux Christi) Op. 29, which premiered in 1896. He revised some of the libretto and vocal solo parts for a Worcester Festival performance in 1899, the same year that the Enigma Variations premiered on June 19th. It is fascinating that the word “Abide” appears in the title of General Gordon’s favorite hymn, “Abide With Me” by Henry Francis Lyte. Elgar planned to compose a symphony in honor of General Gordon when he abruptly altered course and began work on the Enigma Variations. Shortly after General Kitchener’s decisive victory at the Battle of Omdurman in early September 1898, a memorial service for General Gordon was held on September 4. Four chaplains presided over the proceedings. A Presbyterian minister read Psalm 15. An Anglican priest led the soldiers in a recitation of the Lord’s prayer. A Catholic priest removed his helmet and read a special memorial prayer. After these solemn words, the pipers performed Gordon’s favorite hymn “Abide With Me.”

The September 1898 Gordon memorial transpired 47 days before Elgar began officially working on the Enigma Variations. Based on my original research, the 1898 Gordon Memorial Service presents three tantalizing parallels with the Enigma Variations. First, a famous hymn with a three-word title was performed. The covert Theme of the Enigma Variations is also a renowned hymn with a three-word title. Second, a Psalm was read to the assembled troops. The title of Ein feste Burg is the first line of Psalm 46. Third, the Lord’s prayer was recited. Variation XIII is dedicated to Jesus Christ, the author of that famous prayer. These three parallels bolster my thesis that Elgar was originally sketching material for a Gordon Symphony when he abruptly altered course and redirected his creative energies toward the Enigma Variations.

“ST MARTIN” Enigma Titles Ciphers

Thanksgiving is celebrated in the United States on the fourth Thursday of November. It is a national holiday to offer thanks and celebrate the end of the harvest season with a bountiful feast. This holiday traces its roots to English traditions dating back to the Protestant Reformation. In 2023, American Thanksgiving is commemorated on November 23. It is on this special day in a spirit of thanksgiving that I announce the discovery of a series of cryptograms encoded by proximate title letters from the Enigma Variations. These anagrams are collectively labeled the “St. Martin” Enigma Titles Ciphers.

Martin Luther composed the hymn Ein feste Burg, the covert Theme of the Enigma Variations. Luther was baptized on November 11, 1483, the Feast of St. Martin of Tours, receiving his forename in honor of that patron saint. Remarkably, it is possible to generate the acrostic anagram “FEAST ST MARTIN” from adjacent title letters from the Enigma Theme, Variations I through VIII and XIV. The encoding of this anagram cleverly reveals the patron saint of the secret melody’s composer and his first name.

With their titles at opposite ends of the list, why were Variations I and XIV assessed for proximate title letters? One explanation is the close relationship between these two movements that share the same thematic material. Variation XIV restates the opening of Variation I, a movement connected by a bridge passage to the Enigma Theme. These movements are further fused by marriage because Variation XIV is Elgar’s musical self-portrait and Variation I is dedicated to his wife Alice. These connections between the first and last variations support an evaluation of their proximate title letters.

The first element “FEAST” is spelled as a string of contiguous letters by initials from the titles of Variation XIV, the Theme, and Variations I through III. F comes from the subtitle of Variation XIV (Finale). E is the initial for Enigma, the title of the Theme. A is the second initial from the title of Variation I (C. A. E.). S is the third initial from the title of Variation II (H. D. S-P.). T is the third initial in the title of Variation III (R. B. T.).

The second term “ST” is formed by the last two letters of “FEAST” from the titles of Variations II (H. D. S-P.) and III (R. B. T.). “ST” is the abbreviation of the Saint, an English word derived from the Latin sanctus. “MARTIN” is an anagram of adjacent letters from the titles of Variations IV through VIII. M is the second initial in the title of Variation IV (W. M. B.). A and R are the third and first initials of Variation V (R. P. A.). T is the first letter from the title of Variation VII (Troyte). I is the last Roman numeral from Variation VI (Ysobel). The N is the second initial from the title of Variation VIII (W. N.).

The term “FEAST” threaded through the titles of Enigma Variations is a synonym of “FETE”, a word encoded by a sophisticated Polybius cipher in bar 6 of the Enigma Theme. In its opening six bars, Elgar enciphers the complete 24-letter title of the hidden melody. His ingenious methodology encodes each plaintext letter using pairs of melody and bass notes, a process known as fractionation. To harden his cipher, he anagrammatized the 24 letters of the German title “EIN FESTE BURG IST UNSER GOTT” into a series of words and phrases in English, Latin, and what contemporary biblical commentaries classified as Aramaic. Part of the decryption is spelled phonetically, an idiosyncrasy of Elgar’s correspondence. The four languages used in this cryptogram generate the acrostic anagram ELGAR: English, Latin, German, and Aramaic. Remarkably, he autographed the correct solution using a second tier of encipherment that is only accessible after cracking the first layer.

Bar 6 of Elgar’s musical Polybius cipher encodes “FETE”, an English word of French origin that means festival or feast. This is not an isolated use of that term as it also appears in the first sentence of his program note for his 1884 orchestral work Sevillana (Scene Espagnole): “This sketch is an attempt to portray, in the compass of a few bars, the humours of a Spanish fête.” The solution “FETE” in bar 6 of the Enigma Theme resonates with the anagram “FEAST” enciphered by proximate title letters from the Enigma Theme, Variations I through III and XIV. The French translation of the phrase “Feast of St. Martin” is “Fête de la Saint-Martin.” Consequently, the encoding of “FETE” in bar 6 of the Enigma Theme linguistically alludes to the “ST MARTIN FEAST” cipher.

An alternate spelling of “MARTIN” as “MARTYN” is realized by replacing the I with the initial of Ysobel. Martyn is a Gaelic rendering of Martin.

Similar to the “FEAST ST MARTIN” cipher, it is equally feasible to assemble the anagram “FEAST DR MARTIN” from contiguous title letters of the Enigma Theme, Variations I through VIII and XIV.

The title “DR” is obtained from the second initial of Variation II (H. D. S-P.), and the first initial of Variation III (R. B. T.). Martin Luther was awarded a Doctor of Theology degree on October 19, 1512. Two days later on October 21, Dr. Luther was admitted to the senate of the theological faculty at the University of Wittenberg where he served his entire academic career. That date is intriguing as Elgar first performed the Enigma Theme at the piano for his wife on October 21, 1898. The forename “MARTIN” is formed by proximate title letters from Variations IV through VIII.

Elgar studied Latin at three different Roman Catholic schools between 1863 and 1872. He grew up attending Latin Mass, a practice he continued when composing the Enigma Variations in 1898-99. His reading habits would have certainly familiarized him with Luther’s doctorate and Latin manuscripts. As Kevin Mitchell explains in the April 2021 issue of The Elgar Society Journal:

Elgar had a quicksilver mind, that encompassed many disciplines. He was a voracious reader. His reading, although perhaps undisciplined, was wide-ranging and eclectic as befits a self-educated man.

In a letter to Frances Colvin, Elgar explains how his passion for old books extended to some that were stridently Protestant:

When I write a big serious work e.g. Gerontius we have had to starve & go without fires for twelve months as a reward: this small effort [The Crown of India] allows me to buy scientific works I have yearned for & spend my time between the Coliseum & the old book shops: I have found poor Haydon’s Autobiography — that which I have wanted for years & all Jesse’s Memoirs (the nicest twaddle possible) & metallurgical works & oh! All sorts of things — also I can more easily help my poor people [his sister and brother and their families] — so I don’t care what people say about me — the real man is a very shy student & now I can buy books — Ha! Ha! I found a lovely old ‘Tracts against Popery’ — I appeased Alice by saying I bought it to prevent other people from seeing it — but it wd. make a cat laugh.

In his essay “Everything I Can Lay My Hands On’: Elgar’s Theological Library” from the July 2003 issue of The Elgar Society Journal, Geoffrey Hodgkins studiously documents an immense assortment of religious texts that filled Elgar’s personal library. Based on available records, Hodgkins concludes “. . . there could have been more than one hundred bibles and theological books in Elgar’s collection . . .” Elgar referred to these and other borrowed books to compose the librettos for choral works and sacred oratorios. It is significant that many of these resources were written or edited by Protestant scholars. William H. Reed, an accomplished violinist and confidant, recalls how Elgar consulted Roman Catholic and Anglican experts when compiling the libretto for The Apostles:

On 31st July, it is recorded, Elgar, wishing to write his own libretto for the oratorio, The Apostles, began to collect material. As is well known, his knowledge of the Bible and the Apocrypha was profound. He certainly consulted his friends also, both in his own Roman Catholic church and in the Anglican, for instance Canon Gorton, who helped him a great deal in his researches.

Elgar’s interest in Protestant editions of the Bible and biblical commentaries extended to Protestant music. Professor Charles Edward McGuire of Oberlin College and Conservatory observes “. . . Elgar began distancing himself from elements of Catholicism both in private and public communication for the last three decades of his life.” McGuire further notes that Elgar “. . . publicly presented himself as someone who, though Catholic, could appreciate the art and cultural offerings of Protestants . . .” To drive home that point, McGuire refers to remarks by Elgar to Rudolph de Cordova in the May 1904 issue of The Strand Magazine:

I attended as many of the [Anglican] Cathedral services as I could to hear the anthems, to get to know what they were, so as to become thoroughly acquainted with the English Church style. The putting of the fine organ into the Cathedral at Worcester [1874] was a great event, and brought many organists to play there at various times. I went to hear them all. The services at the Cathedral were over later on Sunday than those at the Catholic church, and as soon as the voluntary there was finished at the church I used to rush over to the Cathedral to hear the concluding voluntary.

Additional evidence affirms that Elgar was captivated by Protestant themes. When appointed the chief conductor and artistic director of the Worcestershire Philharmonic Society in the Fall of 1897, Elgar selected the chorus “Wach auf” from Richard Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Master-Singers of Nuremberg) as the signature song for the new society. The lyrics were penned by Hans Sachs, a contemporary of Luther and a Germain Meistersinger, who composed a 700-line long poem called Die Wittenbergisch Natchtigall (The Wittenberg Nightengale) in defense of the German Reformation. Sachs’ allegorical poem depicts Luther as a singing Nightingale heralding the dawn of biblical truths that displace the darkness of a decadent religious cabal that exploits the people for profit. It is highly germane (pun intended) that “Wach auf” is a poetic and musical homage to Luther, the composer of Ein feste Burg. Elgar’s enthusiasm for Protestant tracts, Bibles, and Biblical commentaries included Protestant anthems like “Wach auf” and Ein feste Burg. The program note for the first performance in May 1898 confirms that Elgar was fully aware that “Wach auf” is a “Reformation Song.” On the official letterhead, the singing bird perched atop the “E” in “SOCIETY” represents Luther.

The Mendelssohn quotations in Variation XIII furnish massive clues about the hidden melody and its composer. Felix Mendelssohn was baptized a Lutheran at the age of seven and remained a staunch Protestant throughout his life. He composed the Reformation Symphony in honor of the 300th anniversary of the Augsburg Confession, a founding document of the Lutheran Church. The fourth movement opens with a citation of Ein feste Burg followed by a set of variations. Elgar quotes Mendelssohn to imply by imitation that Mendelssohn cites the covert Theme.

It is significant that the letters that form the “MARTIN” anagram are arranged in an inverted “L” formation. This pattern subtly hints at the initial for Luther, the surname of the covert Theme’s author.

Elgar enclosed the dates of the orchestration within a tilted box on the lower left cover of the Enigma Variations’ autograph score. He abbreviated February twice as “FEb” and penned two “L” brackets separated by a small notch pointing to the year 1899. The abbreviation “FEb” is an anagram of the covert Theme’s initials (EFB), and the “L” brackets provide the initial for its composer (Luther). An opening in one corner of the slanted box shows that it was assembled from two larger “L” glyphs placed end-to-end.

On the earliest surviving short score sketch of Variation XIII, Elgar assigned it the initial “L”. That letter is the initial for Luther. He eventually appended “ML” to the original “L”. The additional letters “ML” are the initials for Martin Luther.

A similar “L” formation resurfaces on the final page of the autograph score in the form of an acrostic anagram that generates “EFB”, the initials of Ein feste Burg. Elgar cleverly underlined this cipher in the shape of an angular “L” to hint at the initial for Luther.

It is equally feasible to assemble the anagram “FEEST DR MARTIN” from adjacent title letters from the Enigma Theme, Variations I through VIII and XIV. “FEEST” is a phonetic realization of “FEAST” with a few intriguing twists. It presents Elgar’s initials (EE) and is an anagram of “FESTE”, the second word from the covert Theme’s title (Ein feste Burg). The F is the initial of Finale, the subtitle of Variation XIV. The first E is the initial for Enigma, the title of the Theme. The second E is the third initial of Variation I (C. A. E.). The S is the third initial of Variation II (H. D. S-P.). The T is the third initial of Variation III (R. B. T.). The title “DR” is obtained from the second initial of Variation II (H. D. S-P.), and the first initial of Variation III (R. B. T.). The forename “MARTIN” is formed by proximate title letters from Variations IV through VIII.

Martin Luther and others referred to him as Dr. Martin. For example, Frederick the Wise called Luther “Dr. Martinus” using his Latin forename, the language of academia and the Roman Catholic Church. In his public speeches and writings, Luther also identified himself as “Dr. Martinus” as illustrated by the following passage:

However, I, Dr. Martinus, have been called to this work and was compelled to become a doctor, without any initiative of my own, but out of pure obedience. Then I had to accept the office of doctor and swear a vow to my most beloved Holy Scriptures that I would preach and teach them faithfully. While engaged in this kind of teaching, the papacy crossed my path and wanted to hinder me in it. How it has fared is obvious to all, and it will fare still worse. It shall not hinder me. In God’s name and call I shall walk on the lion and the adder, and tread on the young lion and dragon with my feet.

On the last page of the autograph score of the Enigma Variations, Elgar inscribed the incorrect completion date “FEb 18 1898”. This poses an anomaly as the original score was completed on February 19, 1899. Why would he write the wrong date? Martin Luther was baptized on November 11, the Feast Day of St. Martin of Tours. The timing of Luther’s baptism accounts for why he was given the forename Martin. Luther died in his hometown of Eisleben on February 18, 1546. As Luther was born and died in that city, it is known officially as Lutherstadt (Luther city). February 18 is the anniversary of Luther’s death. The Feast Day of Dr. Martin Luther is commemorated by some Protestant denominations on February 18.

Why would Elgar encode references to Martin Luther’s Feast Day on February 18? Luther died on that day and is interred before the altar of Castle Church (Schlosskirche) in Wittenberg. Emblazoned around the belfry of Castle Church is the inscription, “EIN FESTE BURG IST UNSER GOTT”. A popular English title of the covert Theme is suggested by the name “Castle Church” as a castle is “A Mighty Fortress.” Every time the bell peals at Schlosskirche, it draws attention to the title of Luther’s most famous hymn encircling the bell tower. Elgar encoded references to Luther’s Feast Day and the anniversary of his death because the title of the covert Theme is prominently displayed on the bell tower of the church that houses Luther’s tomb.

%20.jpg) |

| Bell Tower of Castle Church (Schlosskirche) |

The “FEEST ST MARTIN” title letters anagram suggests the presence of the covert Theme’s title because “FEEST” is an anagram of feste. Further analysis determined that proximate title letters from the Theme, Variations I through III, and XII through XIV encode “EIN FESTE BURG” as a series of overlapping anagrams. “EIN” is encoded by the E from Variation XIV (E. D. U.), the I from XIII, and the N from XII (B. G. N.). “FESTE” is formed by the F from Finale as the subtitle of XIV, E from Variation I (C. A. E.), S from Variation II (H. D. S-P.), T from Variation III (R. B. T.), and E from Enigma. “BURG” is generated by the B and G from XII (B. G. N.), R from the subtitle Romanza from Variation XIII, and U from Variation XIV (E. D. U.). It is also possible to formulate the anagram “Ein” from the first three letters of the Theme’s title (Enigma).

The feasibility of assembling from adjacent title letters the three-word German title “Ein feste Burg” in conjunction with the title and first name of its composer (Dr. Martin) cannot be casually chalked up to coincidence. Their precision and specificity is compelling evidence for a cipher.

The Latin name Martinus comes from Mars, the Roman God of War. Martinus means “of Mars,” “of war,” and “martial.” Born into a pagan family, Martinus converted to Christianity at the age of 1o. He served as a Roman cavalryman, but his faith compelled him to petition the emperor Julian the Apostate to be released from military service. As Martinus confessed, “I am Christ’s soldier: I am not allowed to fight.” Legend holds that while Martinus was still a Roman horse soldier and a catechumen of the faith, he used his sword to cut his military cape in two and gave half to a freezing beggar. Most accounts refer to his military cape as a cloak or robe. In a dream that night, he saw Christ wear his torn cloak and declare to His attending angels, “Martin, who is still but a catechumen, clothed me with this robe.” When Martinus awoke in the morning, his cape was miraculously restored.

|

| Saint Martin Dividing his Cloak by van Dyck, c. 1618 |

It is feasible to assemble the anagram “CAPE ST MARTIN” from proximate title letters from Variations I through VIII. “CAPE” is fashioned from the initials of Variation I (C. A. E.) and the fourth initial of Variation II (H. D. S-P.). This anagram is symbolically divided between Variations I and II whose Roman numerals cleverly encode the fraction ½. Like the Roman numerals, St. Martin was a Roman soldier. St. Martin famously divided his cape in half to share it with a pauper. “ST” is an abbreviation of Saint and is obtained from the third initials of Variation II (H. D. S-P.) and Variation III (R. B. T.). “MARTIN” is generated by adjacent title letters of Variations IV, V, VI, VII, and VIII. The M comes from the second initial of Variation IV (W. M. B.). The A and R are the third and first initials from Variation V (R. P. A.). The T is the initial from the title of Variation VII (Troyte). The I is the second Roman numeral of Variation VI (Yseobel). The N is the second initial of Variation VIII (W. N.).

Referred to as chape in French, St. Martin’s cape became one of the holiest and most prized relics in France. There is only a difference of one letter between the spellings of cape and chape. When war broke out, it was paraded before the French monarchs as a sacred banner to attract divine favor and portend victory. The place where the cloak was preserved was named a chapelle, and the person entrusted with its care was called a chaplain. The English words chapel and chaplain trace their origins to St. Martin’s chape. It is possible to construct the anagram “CHAPE ST MARTIN” with proximate title letters from Variations I through VIII. The French word “CHAPE” is consistent with St. Martin’s service as the Bishop of the French city of Tours. The proximate title letters anagrams “CAPE” and “CHAPE” are analogous to the parallel anagrams “FEAST” and “FEEST”, and “MARTIN” and “MARTYN”. These multiple coded redundancies confirm that these proximate title anagrams were painstakingly constructed.

Why would Elgar encipher St. Martin’s miraculous cape within the titles of the Enigma Variations? Like that miraculous cloak, the Enigma Theme and Ein feste Burg are two melodies cut from the same contrapuntal cloth. The Enigma Variations harbor ciphers about the Turin Shroud and the Sudarium of Oviedo, two sacred linen clothes that covered the crucified body of Christ. A coded reference to a sacred cape cut in two is reminiscent of these two burial clothes that veiled the body of Jesus.

Summation

Elgar taught himself the esoteric science of cryptography. His decryption of an allegedly insoluble Nihilist cipher by John Holt Schooling and the Dorabella Cipher are Elgar’s bone fides. The Enigma Variations is his symphonic homage to cryptography, a work teeming with over 100 cryptograms. These ciphers encode a set of mutually consistent solutions regarding the covert Theme, the Enigma Theme’s “dark saying,” and his secret friend memorialized in Variation XIII. Legacy scholars like Julian Rushton casually deny the existence of these cryptograms by touting the flagrant fiction that Elgar lacked adequate time to craft them. The silver lining of Rushtan’s denialism is that leaves room for independent researchers to detect and decrypt Elgar’s cryptographic morceaux.

Five different lists of the Enigma Variations were made before Elgar settled on the final sequence. Elgar experimented with the order of the movements because he was constructing scores of proximate title letters anagrams. The earliest discovery of this genre is the Letters Cluster Cipher positioned in the titles of Variations XII (B. G. N.) and XIV (E. D. U. & Finale) which encodes the initials of Ein feste Burg as an acrostic anagram. Extensive research uncovered nearly 40 other proximate title letters anagrams expertly woven within the titles of the Enigma Variations. One elaborate example is the anagram “PIE CHRISTI ABIDE” (Pious Christ Abide) encoded by proximate title letters in the first four movements.

The most recent revelations in this field of cryptographic research are the “St. Martin” Enigma Titles Ciphers. Luther was named after that patron saint because he was baptized on the Feast of St. Martin. Proximate title letters in the Enigma Theme, Variations I through VIII and XIV yield the anagrams “FEAST ST MARTIN”. Martin Luther was baptized on November 11, the Feast of St. Martin, and received his forename after that famous French saint. The word “FEAST” is a synonym of “FETE”, an English word of French origin encoded in bar 6 of the Enigma Theme by an advanced Polybius cipher. Elgar used the word fête to characterize his composition Sevillana composed in 1884. The French etiology of “FETE” is consistent with the discovery of the “FEAST ST MARTIN” cipher.

An alternative anagram of “MARTIN” is “MARTYN”, a Gaelic spelling of that forename. Another possible anagram derived from proximate title letters of the Enigma Theme, Variations I through VIII and XIV is “FEAST DR MARTIN”. Luther received a doctorate in theology and referred to himself as Dr. Martin Luther. Some Protestant denominations celebrate the Feast of Martin Luther on February 18, the anniversary of his death. Elgar penned the anomalous completion date “FEb 18 1898” on the last page of the original Finale. However, he actually completed the Enigma Variations one year and one day later on February 19, 1899. The opaque purpose of his incorrect completion date is to pinpoint the Feast of Martin Luther and his tomb at Castle Church which has emblazoned in bold letters around its bell tower “EIN FEST BURG IST UNSER GOTT”.

The “FEEST DR MARTIN” cipher intimated that the hidden Theme’s title may be expertly concealed within the titles of the Enigma Variations because “FEEST” is an anagram of “FESTE”. Further analysis confirmed that contiguous title letters from the Theme, Variations I through III, and XII through XIV produce the anagram “EIN FESTE BURG”. The Latin title of the covert Theme’s author is accompanied by the German title of his most famous hymn.

St. Martin served as a Roman cavalryman and famously cut his military cape in half to share it with a freezing beggar. Proximate title letters generate the anagram “CAPE ST MARTIN”. The “CAPE” anagram is generated by three initials from Variation I (C. A. E.) and the fourth initial from Variation II (H. D. S-P.). In a symbolic gesture, the “CAPE” anagram is divided between Variations I and II whose Roman numerals encode the fraction “½” (I/II). The alternate anagram “CHAPE ST MARTIN” employs the French term for cloak (chape). The coded symbolism of St. Martin's cape alludes to the Enigma Theme and Ein feste Burg as two melodies cut from the same contrapuntal cloth. Elgar’s repeated use of phonetic and linguistic pairs (“CAPE” and “CHAPE”, “FEAST and “FEEST”, and “MARTIN and “MARTYN”) verify the authenticity and careful construction of these proximate title letters anagrams.

To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

.jpg) |

| Stained glass window depicting St. Martin dividing his cape (Wettingen Abbey) |

%22.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please post your comments.