|

| Oxford University |

“. . . H. D. J-P. — he (Var:II) is not a JP but a respectable member of a University Club & therefore worthy of respect not only in St Jame’s St. & Regent’s Park but also in Kensington & Earl Court.”

Edward Elgar in a letter dated March 24, 1904

The late romantic composer Edward Elgar (1857–1934) excelled in coding and decoding secret messages, a discipline formally known as cryptography. In the April 2021 issue of The Elgar Society Journal, chief editor Keven Mitchell acknowledges that for Elgar, “Wordplay, anagrams, spoonerisms, ciphers, and puzzles were fun and remained a lifelong fascination.” His obsession with ciphers merits an entire chapter in Craig P. Bauer’s treatise Unsolved! Most of the third chapter is devoted to Elgar’s brilliant decryption of an allegedly insoluble Nihilist cipher concocted by John Holt Schooling that was featured in an April 1896 issue of The Pall Mall Magazine. A Nihilist cipher is a derivative of the Polybius square. Elgar was so gratified by his solution to Schooling’s reputedly impenetrable code that he specifically mentions it in his first biography released in 1905 by Robert J. Buckley.

Elgar painted the solution to Schooling’s cipher in black paint on a wooden box, an appropriate medium as another name for the Polybius square is a box cipher. His methodical decryption is summarized on a set of nine index cards. On the sixth card, he relates the task of cracking the cipher to “. . . working (in the dark).” His parenthetical expression using the word “dark” as a synonym for a cipher is significant because he deploys that same adjective in the original 1899 program note to characterize the Enigma Theme. It is an oft-cited passage worth revisiting as it lays the groundwork for Elgar’s tripartite riddle:

The Enigma I will not explain – its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’, but is not played . . . So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some later dramas – e.g., Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’ – the chief character is never on the stage.

Elgar employs the words “dark” and “secret'' interchangeably in a letter to August Jaeger penned on February 5, 1900. He writes, “Well — I can’t help it but I hate continually saying ‘Keep it dark’ — ‘a dead secret’ — & so forth.” One of the meanings of dark is secret, and a saying is a series of words that form a phrase or adage. Based on these definitions, Elgar’s cryptic expression — “dark saying” — is a coded way of admitting there is an enciphered message in the Enigma Theme.

Mainstream scholars speculate that the Enigma Variations have no answer because Elgar allegedly concocted the notion of an absent principal Theme as an afterthought, practical joke, or marketing gimmick. The editors of the Elgar Complete Edition casually deny the likelihood of any covert counterpoints or cryptograms. Relying on Elgar’s recollection of playing new material at the piano to gauge his wife’s reaction, they tout the standard lore that he must have extemporized the idiosyncratic Enigma Theme, mirabile dictu, without any forethought or planning:

There seems to have been no specific ‘enigma’ in mind at the outset: Elgar’s first playing of the music was hardly more than a running over the keys to aid relaxation. It was Alice Elgar’s interruption, apparently, that called him to attention and helped to identify the phrases which were to become the ‘Enigma’ theme. This suggests it is unlikely that the theme should conceal some counterpoint or cipher needed to solve the ‘Enigma’.

Such a blanket renunciation conveniently relieves scholars of the obligation to probe for ciphers. The huge irony is proponents of that myopic denialism extol the validity of their position based on a dearth of evidence for which they never executed a diligent or impartial search. Such a ridiculous state of affairs is a textbook case of confirmation bias pawned off as scholarship.

A more sensible view (embraced by those who take Elgar at his published word) accepts the challenge that there is a famous melody lurking behind the Variations’ contrapuntal and modal facade. In his 1905 biograph, Elgar plainly states, “The theme is a counterpoint on some well-known melody which is never heard . . .” Most scholars insist the answer can never be known because Elgar allegedly took his secret to the grave. This rigid absolutism presumes he never wrote down the solution for posterity to discover. Such an intransigent opinion glosses over or blatantly ignores Elgar’s documented obsession with cryptography. That incontestable facet of his psychological profile raises the prospect that the solution is skillfully encoded within the orchestral score of the Enigma Variations.

A decade of trawling the Enigma Variations has netted over one hundred cryptograms in diverse formats that encode a set of mutually consistent and complementary solutions. Although that sum may seem extraordinary, it is entirely consistent with Elgar’s obsession with ciphers. More significantly, the solutions give definitive answers to the riddles posed by the Enigma Variations. What is the secret melody to which the Enigma Theme is a counterpoint and serves as the melodic unifier for the ensuing movements? Answer: Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by Martin Luther. What is Elgar’s “dark saying” hidden within the Enigma Theme? Answer: A musical Polybius box cipher located in the opening six bars. Who is the secret friend and inspiration behind Variation XIII? Answer: Jesus Christ, the Savior of Elgar’s Roman Catholic faith.

Some “EFB” Ciphers

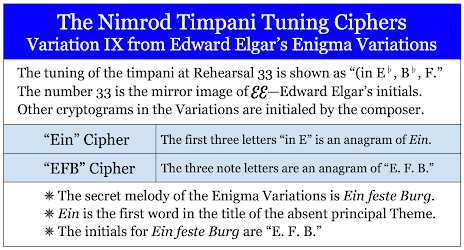

A distinct subset of ciphers sprinkled throughout the Enigma Variations encode the initials of Ein feste Burg. Some remarkable examples are the Enigma Theme Keys Cipher, Nimrod Timpani Tuning Cipher, Variation XII through XIV Letters Cluster Cipher, Mendelssohn Fragments Scale Degrees Cipher, and the Original and Extended Ending Ciphers. The Enigma Theme is written in the parallel modes of G minor and G major. The accidentals for those two key signatures (B-flat, E-flat, and F-sharp) are an anagram of “EFB.” The Enigma Theme’s keys unlock the initials of the covert Theme. The first three letters of “Enigma” are an anagram of the Ein, the first word from the covert Theme’s title.

Variation IX (Nimrod) begins at Rehearsal 33 in measure 308. The tuning of the timpani for this movement is specified as E-flat, B-flat, and F. Those three note letters are an anagram of “EFB.” The first three letters in the timpani’s tuning directions (“in E . . .”) is a thinly disguised anagram of Ein, the first word in the title Ein feste Burg. This is the same pattern observed with the first three letters of the Theme’s title — Enigma.

Variation XIII has a cryptic title consisting of three hexagrammic asterisks enclosed by parentheses which present as (✡ ✡ ✡). The absent initials signified by the starry asterisks are enciphered as an acrostic anagram by the titles of the adjoining movements: XII (B. G. N.) and XIV (E. D. U. & Finale). Elgar frames the riddle posed by the cryptic title with the correct solution as an acrostic anagram using the titles of the adjacent movements.

There are four melodic incipits in Variation XIII consisting of four notes from a subordinate theme of Felix Mendelssohn’s concert overture Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt (Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage). Two are performed in A-flat major, one in F minor, and another in E-flat major. These Mendelssohn fragments encode the initials “EFB” for Ein feste Burg using the number of statements in a given key to pinpoint the scale degree of that particular mode. Two Mendelssohn fragments in A-flat major identify the second scale degree of that key which is B-flat. There is one Mendelssohn fragment in F minor and another in E-flat major. The first scale degrees of those two keys are F and E-flat, respectively.

On the final page of the manuscript score with the original ending of Variation XIV, Elgar penned Fine, a paraphrase drawn from Torquato Tasso’s La Gerusalemma Liberata (Jerusalem Delivered) beginning with the word Bramo, and his autograph. The first letters of these three entries form the acrostic anagram “EFB”, the initials of the covert Theme. The anomalous date on that page — “FEb 18 1898” — furnishes yet another anagram of “EFB” that accompanies the anniversary of Luther’s death on February 18, 1546. The tempo marking for the Enigma Theme is 63 quarter beats per minute, a number that corresponds to Luther’s age of death. Luther is interred in front of the pulpit of Schlosskirche (Castle Church) in the city of Wittenberg.

Following the June 1899 premiere of the Enigma Variations, Elgar appended 96 bars to Variation XIV, his musical self-portrait. His signature on the final page of this addition is accompanied by the word Fine and the location (Birchwood Lodge) where he completed the manuscript. The first letters of these three entries form an acrostic of the initials for Ein feste Burg. The L in “Lodge” even divulges the initial of its composer (Luther). That same initial is reinforced by the quotation at the upper right of the page from stanza XIV of the poem Elegiac Verse by Longfellow.

This overview illustrates how Elgar encodes the initials “EFB” using a variety of different cryptograms. Most rely on the use of anagrams and acrostics to encode information. These ciphers represent a set of variations on the covert Theme’s initials. The “EFB” decryption is consistent with the majority of the titles from the Enigma Variations which are comprised of different sets of initials.

The Oxford “EFB” Cipher

Three musical friends depicted in the Enigma Variations attended constituent colleges of Oxford University. The dedicatee of Variation II is the pianist Hew David Steuart-Powell who graduated from Exeter College. The dedicatee portrayed in Variation XII is the cellist Basil George Nevinson, another graduate of that same institution. The friend sketched in Variation V is the pianist Richard Penrose Arnold, a student of Balliol College. All three were active in the Oxford University Musical Society (OUMS) founded in 1872. Another Oxford graduate portrayed in the Enigma Variations is Troyte Griffith of Variation VII who attended Oriel College. Unlike his three Oxford peers, Troyte was unmusical and not actively engaged with the Oxford University Musical Society. The musical trio of Oxford students — Steuart-Powell, Arnold, and Nevison — were friends of Elgar’s wife and entered his social sphere following their marriage in May 1889.

Exeter College was founded in 1314 and adopted the Latin motto “Floreat Exon” (Let Exeter Flourish). Balliol College was founded in 1263 but does not advertise a collegiate motto. Remarkably, it is possible to obtain the initials “EFB” as an acrostic from the first letters of Exeter, its Latin motto “Floreat Exon”, and Balliol.

Exeter

Floreat Exon

Balliol

It is equally feasible to generate the acrostic anagram “EFB” using Exeter’s motto and the name Brasenose.

Floreat Exon

Balliol

Elgar ingeniously encodes the initials of Ein feste Burg as an acrostic anagram using the college names and motto associated with friends portrayed in Variations II, V, and XII.

Variations II and XII depict graduates of Exeter. Variation V portrays a student of Balliol. Applying an elementary number-to-letter key (1 = A, 2 = B, 3 = C, etc.) to the Roman numerals II, V, and XII yields in ascending order the plaintext B, E, and L, respectively. These letters are a phonetic spelling of bell, a reading supported by Elgar’s personal correspondence which is adorned with phonetic spellings. Could this coded allusion ring a bell regarding the identity of the secret melody? Emblazoned around the belfry of Castle Church in Wittenberg is the inscription, “EIN FESTE BURG IST UNSER GOTT”. A popular English title for the covert Theme is suggested by the name “Castle Church” as a castle is “A Mighty Fortress.” Whenever the bell peals at Schlosskirche, it draws attention to the title of Luther’s most famous hymn encircling the bell tower.

%20.jpg) |

| Bell Tower of Castle Church (Schlosskirche) |

The first two letters — B and E — correspond to the initials for Balliol and Exeter. They also furnish two out of the three initials from Ein feste Burg. The remaining L is the initial appearing on the earliest surviving short score sketch of Variation XIII. L is the initial for Luther, the composer of Ein feste Burg.

The “bell” decryption encoded by the Roman numerals associated with the three Oxford graduates portrayed in the Enigma Variations presents multiple connections to the covert Theme and secret friend. The loudest bell at Oxford University is a large single bell called “Great Tom” mounted in Tom Tower. Remarkably, the word “Tower” occurs in at least half a dozen English translations of Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. These titles are listed below:

- A tower of strength is our God’s name

- A tower of strength our God doth stand

- A strong tower is the Lord our God

- A tower of strength is God our Lord

- A tower of strength our God is still

- A Tower of safety is our God

These titles are cataloged in the 1892 edition of A Dictionary of Hymnology compiled by John Julian:

A musical Polybius cipher embedded in the Mendelssohn fragments of Variation XIII encodes the three-word title “A Strong Tower.” It is significant that “Tower” appears in that English rendering of Ein feste Burg. The decryption bell cleverly hints at the word tower, a term in at least six English titles for the absent principal Theme. The key to the Mendelssohn Polybius Box Cipher is displayed below:

The bell Great Tom came from Osney Abbey, an Augustinian monastery dissolved in 1539 and converted into an Anglican cathedral. This shift from a Roman Catholic to Protestant institution mirrors the experience of Martin Luther who joined an Augustinian monastery and was eventually excommunicated by the Roman Catholic Church at the Diet of Worms in 1521. The initials for Tom Tower (TT) where Big Tom is housed parallel those for Torquato Tasso, an Italian poet paraphrased by Elgar at the end of the original Finale. Tom Tower stands over the gate to Christ Church College. The secret friend memorialized in Variation XIII is Jesus Christ. Christ Church College was founded by King Henry VIII in 1546, the year that Martin Luther died. This intersects with the erroneous completion date penned at the end of the original Finale (“FEb 18, 1898”) as it marks the 352nd anniversary of Luther’s death.

In the absence of a collegiate motto, Balliol College must accede to the motto of Oxford University: Dominus illuminatio mea. That Latin motto is an incipit from Psalm 27 that opens in the first verse with, “The Lord is my light.” It is elegant that Oxford’s motto pinpoints the biblical inspiration for the covert Theme — Psalm — as well as the secret friend memorialized in Variation XIII — “The Lord.” Oxford’s motto “The Lord is my light” resonates with a cipher on the earliest surviving short score of Variation XIII that encodes a classical Latin spelling of light as “LVX.”

Elgar’s first sacred oratorio is The Light of Life (Lux Christi) Op. 29, a setting of Jesus restoring sight to a man born blind as described in the Gospel of John. Elgar’s Latin original title Lux Christi means “Light of Christ.” The oratorio premiered in Worcester at the 1896 Three Choirs Festival, three years before the completion of the Enigma Variations. The solo parts were extensively revised in 1899.

There are numerous coded references to Psalm and the number “46” in Variation II. The title area of the manuscript score encodes the acrostic anagrams “Hide Psalm” and “I hid Psalm.” The precise chapter is divulged by the number of periods (4) and letters (6) in the published title as well as by that movement’s 46-second duration.

Performance terms in the first bar of that movement also generate an acrostic anagram of Psalm. This cipher relies on the first letters of p[iano], stacc., Allegro, and the 3 from the time signature that may be rotated to resemble a cursive M. This flexible treatment of the 3 glyph is shown in the Dorabella Cipher where Elgar reorients that character to resemble an E, 3, and M. Chapter 46 is encoded by the total of all of the characters in the performance terms deployed in bar 41. That same sum is also produced by adding the bar number (41) to the Rehearsal number (5). Such redundancies serve as confirmation of the authenticity of these mutually supportive ciphers.

Performance directions in the second variation encipher seven abbreviations of Psalm (Ps) as acrostic anagrams. These ciphers use the same encoding technique observed with the Mendelssohn quotations in Variation XIII. These coded abbreviations appear in the staves of the first violin (bar 41), second violins (bar 43), cellos and contrabasses (bar 58), timpani (bar 83), flute (bar 93), and clarinet (bar 95). In bar 87, the first violins and violas play three notes in octaves — F, B, and E — which anagrammatize the initials of Ein feste Burg. The number 46 accompanies these coded abbreviations of Psalm in bars 41, 43, 93, and 95. The added sixth chord on the fourth scale degree of G minor in bar 94 encodes the numerals 4 and 6. The chord progression in bars 94 and 95 also encodes the numbers 4 and 6. Two E-flats in the accompaniment of bars 94-95 suggest a coded version of Elgar’s initials (EE).

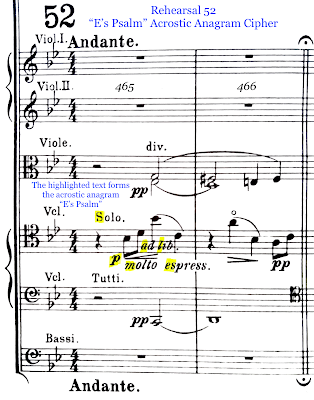

Like the second variation, Variation XII encodes the word Psalm. The performance directions assigned to the cello solo at the beginning of that movement form an acrostic anagram of “E’s Psalm”. Recognizing that “E” represents Elgar’s initials, this anagram may be translated as “Elgar’s Psalm”. This cipher appears in bar 465. The first two numerals are 46, the chapter from the Psalms that inspired Ein feste Burg. The remaining 5 corresponds to the fifth letter of the alphabet, the initial for Elgar.

The reluctance of legacy scholars to acknowledge or study Elgar's pioneering use of cryptography in his works is both a genuine enigma and a blessing in disguise. The more they delay devoting precious time and resources to this burgeoning field of study, the more opportunities for discovery remain the exclusive domain of independent researchers like myself. To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

%22.jpg)

%20page%20322.png)

%20page%20323.png)

%20page%20324%20.png)

%20page%20325.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment