Edward Elgar (Postcard c. 1910)

During railway journeys amuses himself with cryptograms; solved one by John Holt Schooling who defied the world to unravel his mystery.

Robert J. Buckley in his 1905 biography of Sir Edward Elgar

Today is the 319th day of the year with 46 days remaining until the arrival of 2023. November 15th marks the twentieth anniversary of “I Love To Write Day” founded by John Riddle. Now is an opportune moment to publish my 204th installment exploring the symphonic Enigma Variations by the British romantic composer Edward Elgar. Elgar excelled in coding and decoding secret messages, a discipline formally known as cryptography. His obsession with that esoteric art merits an entire chapter in Craig P. Bauer’s treatise Unsolved! The bulk of its third chapter is devoted to Elgar’s brilliant decryption of an allegedly insoluble Nihilist cipher conceived by John Holt Schooling that was published in an April 1896 issue of The Pall Mall Magazine. A Nihilist cipher is a derivative of the Polybius square. Elgar was so gratified by his solution to Schooling’s reputedly impenetrable code that he specifically mentions it in his first biography released in 1905 by Robert J. Buckley.

Elgar painted his solution in black paint on a wooden box, an appropriate medium as another name for the Polybius square is a box cipher. His methodical decryption is summarized on a set of nine index cards. On the sixth card, Elgar relates the task of cracking the cipher to “. . . working (in the dark).” His parenthetical expression using the word “dark” as a synonym for a cipher is significant because he deploys that same phraseology in the original 1899 program note to characterize the Enigma Theme. It is an oft-cited passage worth revisiting as Elgar lays the groundwork for his tripartite riddle:

The Enigma I will not explain – its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’, but is not played . . . So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some later dramas – e.g., Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’ – the chief character is never on the stage.

Elgar employed the words “dark” and “secret'' interchangeably in a letter to August Jaeger penned on February 5, 1900. He wrote, “Well — I can’t help it but I hate continually saying ‘Keep it dark’ — ‘a dead secret’ — & so forth.” One of the meanings of dark is secret, and a saying is a series of words that form a phrase or adage. Based on these definitions, Elgar’s cryptic expression — “dark saying” — is a coded way of saying there is an enciphered message in the Enigma Theme.

A decade of trawling the Enigma Variations has netted over one hundred cryptograms in diverse formats that encode a set of mutually consistent and complementary solutions. Although that sum may seem extraordinary, it is entirely consistent with Elgar’s obsession with ciphers. More significantly, their solutions give definitive answers to the riddles posed by the Enigma Variations. What is the secret melody to which the Enigma Theme is a counterpoint and serves as the melodic foundation for the ensuing movements? Answer: Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by Martin Luther. What is Elgar’s “dark saying” hidden within the Enigma Theme? Answer: A musical Polybius box cipher located in the opening six bars. Who is the secret friend and inspiration behind Variation XIII? Answer: Jesus Christ, the Savior of Elgar’s Roman Catholic faith.

The first persuasive evidence for the existence of musical cryptograms in the Enigma Variations was uncovered by Richard Santa back in 2009. A retired engineer and Elgar enthusiast, Santa (whose name means “Holy” and “Saint”) found the Enigma Theme’s opening bar encodes Pi, a mathematical constant describing the ratio of any circle’s circumference and its diameter. In his groundbreaking research, Santa determined the first four melody notes of the Enigma Theme sequentially approximate a rounded form of Pi (3.142) via its scale degrees in the key of G minor. Its opening melody notes are B-flat, G, C, and A; their corresponding scale degrees are 3, 1, 4, and 2, respectively. Santa generously shared an early draft of his paper with me during the summer of 2009 before it was published by Columbia University’s journal Current Musicology in March 2010.

Santa’s paper offered the tantalizing prospect there could be other cryptograms lurking in the Enigma Variations. That hunch was bolstered in August 2009 when Dr. Clive McClelland of Leeds University kindly forwarded to me his paper Shadows of the evening: New light on Elgar’s ‘dark saying.’ Although his melodic solution fails to satisfy key conditions articulated by Elgar, I eagerly read McClelland’s essay and was impressed by some of his insights. For instance, his analysis of the Enigma Theme’s opening six bars finds circumstantial evidence for a cipher. The basis for this suspicion is that regularly spaced quarter rests at the outset of each bar suggest spaces between words. As McClelland surmises:

Elgar’s six-bar phrase is achieved by the characteristic four-note grouping, repeated six times with its reversible rhythm of two quavers and two crotchets. This strongly suggests the cryptological technique of disguising word-lengths in ciphers by arranging letters in regular patterns.

Following McClelland’s line of reasoning, quarter rests uniformly dispersed over six bars with four melodic notes per bar would suggest that Elgar’s “dark saying” consists of six words with exactly twenty-four letters. Such a conclusion resonates with my thesis that Luther’s Ein feste Burg is the absent Theme because its complete German title is six words with a sum total of twenty-four letters. The numeric parallels are far too precise to be casually chalked up to coincidence. The synergy of Santa’s and McClelland’s insights precipitated an intense search for a musical cryptogram in the opening six bars of the Enigma Theme. My quest began in October 2009 and culminated in the detection and decryption of a musical Polybius cipher in February 2010. My discovery was first announced in September 2010 and has proven to be my most popular article. A more succinct overview of my decryption was released in August 2019. Below is the decryption of that sophisticated Polybius cipher.

The Enigma Theme’s Polybius cipher is the most sophisticated of all the cryptograms in the Variations. It uses 24 pairs of melody and bass notes to encode the 24 plaintext letters from the title Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. Elgar ingeniously reshuffles those 24 letters into a series of anagrams in English, Latin, and what he reasonably believed to be Aramaic in accordance with popular biblical commentaries near the turn of the century. Four of the six anagrams are spelled phonetically, an unexpected feature consistent with Elgar’s correspondence that incorporates inventive phonetic spellings. Some examples of these atypical spellings are listed below:

- Bizziness (business)

- çkor (score)

- cszquōrrr (score)

- fagotten (forgotten)

- FAX (facts)

- frazes (phrases)

- gorjus (gorgeous)

- phatten (fatten)

- skorh (score)

- SSCZOWOUGHOHR (score)

- Xmas (Christmas)

- Xqqqq (Excuse)

- Xti (Christi)

Elgar’s reliance on four languages mingled with phonetic spellings was ostensibly intended to frustrate conventional decryption methods that presume a coded message is restricted to one language and conventional spellings. His education in three Roman Catholic schools ensured he was tutored in both English and Latin. He also studied German in the hopes of attending the Leipzig Conservatory founded by Felix Mendelssohn. Remarkably, the first letters of these four cipher languages is an acrostic anagram of “ELGAr”:

- English

- Latin

- German

- Aramaic

In a stunning cryptographic feat, Elgar signed the correct decryption to his musical Polybius box cipher employing a second tier of encryption only revealed by successfully unlocking the first. This is Elgar’s proverbial sealed envelope bearing the melodic solution to his Enigma. Supreme confidence in his unexpected answer is assured by Elgar’s stealth signature. He autographed the solution because he recognized it would be unguessed and polemical.

Elgar deposited subtle clues on the title page of the autograph score hinting at a Polybius square cipher. The most conspicuous is a tilted square on the lower left-hand side of the cover. This geometric figure overlays the same staves on the following page where he orchestrated Enigma Theme’s opening bars that house a musical Polybius square cipher. This is the only known instance where Elgar drew a square on the cover of a symphonic score. Within his tilted square, Elgar inserted multiple anagrams of the initials “EFB” accompanied by the capital letter “L” thinly disguised as a square bracket.

|

| The Enigma Variations Autograph Score Title Page |

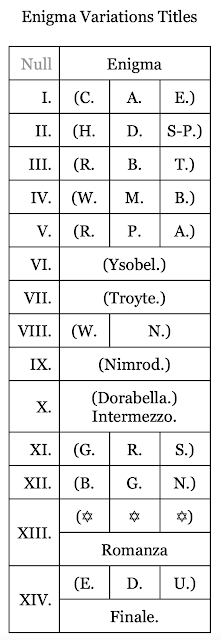

Another breakthrough in 2013 unveiled the meaning and significance of the three asterisks in the cryptic title of Variation XIII (✡ ✡ ✡). It was determined those absent letters are cleverly encoded by the first initials of the titles from the adjoining movements. The first initials from the titles of Variations XII (B. G. N.) and XIV (E. D. U. & Finale) are an acrostic anagram of the initials for the covert Theme (Ein Feste Burg). Elgar deftly frames the question posed by the three asterisks with the answer hidden in plain view.

Elgar experimented with five different orderings of the movements, a process that, in retrospect, was carried out to construct this particular cipher. Such a possibility eludes musicologists such as Julian Rushton who irrationally speculate that Elgar lacked the time to construct any cryptograms. Such a conclusion conflicts with the established timeline. Elgar began composing the Enigma Variations on the evening of October 21, 1898, and completed the orchestration on February 19, 1899. Later that year, he appended 96 measures to the Finale between June 30 and July 20 for an additional 21 days. In all, Elgar invested 142 days composing the Enigma Variations, a period that afforded more than sufficient time and opportunity for Elgar to indulge his passion for cryptography.

The titles of the Enigma Variations are summarized in the table exhibited below. Its fifteen movements with divergent titles have a grand total of 187 characters. There is one dash, three asterisks, and fourteen pairs of parentheses for a total of 28, and 46 periods. There are nine sets of initials with 27 letters, seven words with 49 letters, and fourteen Roman numerals with 33 letters.

The acrostic anagram from the titles of Variations XII and XIV which unveils the initials of Ein feste Burg is an elementary cryptogram labeled the Letters Cluster Cipher. Its discovery eventually precipitated a much broader analysis of all the titles from the Enigma Variations with the goal of uncovering other meaningful and relevant groupings of proximate title letters. This approach is markedly dissimilar from Stephen Pickett’s surgical cherry-picking of single initials from titles and names to assemble a purported solution for the absent Theme. My investigation uncovered an array of terms linked to the absent Principal Theme, the Enigma’s “dark saying,” and the secret friend. The Letters Cluster Cipher was the proverbial tip of a much larger iceberg of coded information.

Another superlative example of a proximate title letters anagram found in the opening three titles of the Enigma Variations is “PIE CHRISTI ABIDE” (Pious Christ Abide). The first two words are in Latin, and the third is English. Remarkably, the spelling of the first word (PIE) is nearly identical to Pi, the mathematical ration lurking in the Enigma Theme's opening bar. In that same measure, a musical Polybius cipher encodes “GSUS”, a phonetic rendering of Jesus. Merging these companion decryptions from bar 1 yields “Pi GSUS” (Pi Jesus), a close approximation of “PIE CHRISTI.” It is surely significant that these divergent ciphers generate mutually consistent and corresponding solutions. Between 1863 and 1872, Elgar attended three Roman Catholic schools where he studied both languages. Remarkably, the spelling of the first word (PIE) is nearly identical to Pi, the mathematical ratio discovered by Santa lurking in bars 1 and 11 of the Enigma Theme. The Latin word for Christ appears in the title of Elgar’s first sacred oratorio, Lux Christi Op. 26. Published under the Anglicanized title The Light of Life, it premiered in 1896 and was extensively revised in 1899 — the same year Elgar completed his Enigma Variations.

It is a privilege to report the discovery of yet another set of interlocking anagrams within the opening three titles of the Enigma Variations. Contiguous title letters in those first three movements encode the anagram “HIDE PSAlm.” The first word (HIDE) is formed by letters from Variations I (C. A. E.) and II (H. D. S-P.). The second term (PSAlm) is sourced from letters in the Theme (Enigma), Variation I (C. A. E.), and II (H. D. S-P.). Although there is no letter L in these titles, the Roman numeral for the number one (I) is a homoglyph (l) of a lowercase L. Interpolating the “I” as a lowercase “l” is consistent with Elgar’s pliable treatment of the E glyph in his Dorabella Cipher to duplicate the letters M and W. The anagram “HIDE PSAlm” accords with Elgar’s novel treatment of Ein feste Burg as the covert Theme to the Enigma Variations.

Another possible anagram obtained from proximate title letters in the opening three movements is “C EE HIID PS”. The letters required for this anagram are sourced from the initial of the Theme (Enigma), the first and third initials from Variation I (C. A. E.), the Roman numerals and initials from Variation II (H. D. S-P.). “C” is a homonym of see. “EE” is Elgar’s initials. “HIID” is a phonetic rendering of hide. “PS” is a standard abbreviation of Psalm. The proximate title letters anagram “C EE HIID PS” may be fully decoded as “See Edward Elgar hide Psalm.”

There are 150 chapters in the Book of Psalms. Out of so many possibilities, which Psalm did Elgar conceal? The answer is furnished by the number of letters in the titles of Variations I and II. There are four letters in the title of the first variation (ICAE), and six in the second (IIHDSP). When paired together, the attendant sums of these title letters from these contiguous movements convey a coded version of the number 46. When considered in the context of the “HIDE PSAlm” anagram, that figure implicates chapter 46 of the Psalms, the afflatus for Martin Luther's Ein feste Burg. This conclusion is bolstered by the “D” in Variation II which stands for David, the author’s name for Psalm 46.

|

| David Playing the Harp by Jan de Bray (1670) |

In a revealing gesture, Elgar substitutes the Star of David for standard asterisks in the title of Variation XIII (✡ ✡ ✡). This marine movement with the anomalous Mendelssohn quotations from the overture Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage is dedicated in secret to Jesus Christ. Elgar’s choice of stars is deeply symbolic as one of the many titles for Jesus is “Son of David” (e.g., Matthew 1:1, Matthew 9:27, Matthew 12:22-23, Matthew 15:21-22, Matthew 20:30-31). Stars are closely associated with Christ. A star announced his birth (Matthew 2:1-2) to the wise men from the East. In a vision, John of Patmos saw Jesus holding seven stars in his right hand (Revelation 1:16). Yet another title for Jesus is the “bright morning star” (Revelation 22:16). Relying on these biblical references, there is a sound theological foundation for concluding that stars are emblematic of Christ.

The titles anagram “HIDE PSAlm” may be elaborated by the inclusion of chapter 46, the initial “E” from Enigma, and “C” from Variation I. With these additional initials, it expands to “C E HIDE PSAlm 46.” C is a homonym of see. E is the initial for Elgar employed extensively in his correspondence and wife’s diary. Armed with these insights, this enhanced anagram may be read phonetically as “See Elgar hide Psalm 46.” Appending that chapter number to the alternate anagram yields “C EE HIID PS 46” which reads as “See Edward Elgar hide Psalm 46.” The precision and specificity of these anagrams are nothing short of extraordinary, supplying an apt characterization of Elgar’s novel treatment of Ein feste Burg as the hidden principal Theme. As a stealth form of authentication, Elgar inserted his initials within this proximate title letters cryptogram. Elgar enjoyed signing his work.

Elgar initialed other cryptograms embedded within the Enigma Variations. For example, seven discrete performance directions in the first bar of the Enigma Theme generate the acrostic anagram “EE’s Psalm.” There are precisely 46 characters in this remarkable cryptogram, a sum that implicates Psalm 46. Like the titles anagram cipher previously described, this decryption unveils the author’s initials.

To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

.png)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment