Lux, Dux, Rex, Lex. On the northern wall of the church of St. Pierre de Dorat is sculpted a simple Greek cross with this inscription. It represents the Cross as the light and guide and law and ruler of the world. These all centre in the cross, and radiate from it.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in The Golden Legend

The composer Edward Elgar encoded a series of words and phrases in the titles of the Enigma Variations. These decryptions are documented in my article Elgar’s Proximate Title Letters Enigma Ciphers. The encipherment technique relies on adjacent letter formations in the titles. Some remarkable examples are Christ, Abide, Pieta, Lamb, Bride, Bread, and Beads. These solutions reinforce the conclusion that Jesus is the secret friend portrayed in Variation XIII. Elgar experimented with five lists of the Enigma Variations before finalizing the order. Now the explanation for these varying lists is known as he was devising a series of cryptograms within those titles.

Those who hastily dismiss these discoveries require constant reminding that Elgar was an expert in cryptography. This fact merits an entire chapter in Craig P. Bauer’s treatise Unsolved! A decade of concerted analysis has netted over ninety cryptograms within the Enigma Variations. These ciphers encode a set of mutually consistent solutions that provide definitive answers to the core questions posed by the Enigma Variations. What is the secret melody to which the Enigma Theme is a counterpoint and serves as the melodic cornerstone of each movement? Answer: Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by Martin Luther. What is Elgar’s “dark saying” ensconced within the Enigma Theme? Answer: A musical Polybius cipher situated in measures 1-6. Who is the secret friend and inspiration behind Variation XIII? Answer: Jesus Christ, the Savior of Elgar’s Roman Catholic faith.

One of Elgar’s other passions was the poetry of the American author Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. This interest was nurtured and fed from early childhood by his mother, Ann Elgar, who saturated her brood with Longfellow’s artistic weltanschauung through regular readings of his works. She was not alone in her admiration for that great American poet and ambassador of Christianity. Two years after Longfellow’s death, the English public erected a memorial bust in the Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey next to no less than Chaucer. During his burgeoning career as a composer, Elgar turned to Longfellow’s works to stoke his creative output. Michael Pope concludes, “. . . Longfellow possessed the imponderable spiritual qualities required to fire Elgar’s imagination.”

The poetry and prose of Longfellow served as the stimulus for at least five of Elgar’s compositions. The first is Spanish Serenade Op. 23, a work for chorus and orchestra written in 1892 based on Act I of Longfellow’s play The Spanish Student. The second is The Black Knight Op. 25, an oratorio composed in 1893 and inspired by Longfellow’s translation of Uhland’s “Der schwarze Ritter” from his novel Hyperion: A Romance:. The third is Rondel Op. 16 No. 3, a song for voice and piano set in 1894. The fourth is The Saga of King Olaf, a cantata composed in 1896 that was inspired by Longfellow’s epic poem by the same title. The fifth is The Apostles, a sacred oratorio that premiered in 1903 and is based partly on Longfellow’s The Divine Tragedy (1871). Longfellow’s epic Christian poem is part of a trilogy with The Golden Legend (1851) and The New England Tragedies (1868).

There is a famous compilation of medieval hagiographies about the saints compiled and written by Jacobus da Varagine called The Golden Legend. It is known by the Latin titles Legenda Aurea and Legenda Sanctorum. The name of Longfellow’s epic poem was drawn from this medieval work. There is a unique association between the words dark, enigma and Christ in Longfellow’s The Golden Legend. The heroine Elsie says to Prince Henry in Chapter IV, “Faith alone can interpret life, and the heart that aches and bleeds with the stigma / Of pain, alone bears the likeness of Christ, and can comprehend its dark enigma.” Elgar wrote in the original 1899 program note, “The Enigma I will not explain — it’s ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed . . .” With those carefully chosen words, Elgar deftly alludes to one of Longfellow’s most influential poetic works.

Longfellow’s poetry was also the impetus for Arthur Sullivan’s sacred cantata The Golden Legend. Elgar was intimately familiar with this work as he served as a sectional violinist in performances of it during May 1887, September 1887, and November 1892. He also attended another performance in September 1898, a month before he began composing the Enigma Variations. Elgar’s daughter Carice wrote, “My father always spoke with great feeling and respect for Sullivan and admired The Golden Legend.” There is a coded allusion to The Golden Legend in the first bridge passage (bars 18-19) that connects the Enigma Theme to Variation I.

Elgar was knowledgeable about Longfellow’s The Golden Legend which inspired Sullivan’s greatest cantata. The title page of The Golden Legend features a Greek Cross with the overlapping Latin inscription, “Lux, Dux, Rex, and Lex.”

Longfellow explained that this Christogram “. . . represents the Cross as the light and guide and law and ruler of the world.” This description encapsulates his Christian worldview that attracted and retained Elgar’s unbridled attention for decades. The Latin word Lux means “Light” and appears in the title of Elgar’s first sacred cantata, Lux Christi. Dux is the Latin word for “Leader” or “Ruler.” The Latin term Rex means “King.” Lex is Latin for “Law.”

A reassessment of the proximate letters in the titles of Variation XIII and XIV reveals the coded emergence of the Latin terms from Longfellow’s Cross.

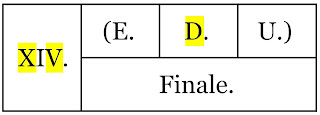

The first word to appear from Longfellow’s Cross is an acrostic anagram of REX. This word is formed by the first letter of the subtitle Romanza from Variation XIII, Elgar’s first initial (E. D. U.), and the first Roman numeral from Variation XIV. This Latin term was written on the sign posted at the crucifixion of Jesus that listed one of his crimes as being the “King of the Jews” (Rex Judaeorum).

The next word from Longfellow’s Cross proceeding counterclockwise is DVX. This word is formed in reverse order by every other letter from the Roman numerals and initials of Variation XIV (E. D. U.). It is pronounced “Dux” because V is the equivalent of the letter U in the classical Latin alphabet. It is fitting that the Latin word for “Leader” is encoded in the title of Elgar’s movement. As the composer of the Enigma Variations, he served as the leader of this ambitious project.

It is significant that the Latin word DUX is also enciphered by the first Roman numeral and second and third initials from the title of Variation XIV (E. D. U.). Elgar enciphered two spellings of this Latin word by efficiently using four out of six letters available from the three Roman numerals (XIV) and three initials (E. D. U.) of his movement.

The earliest sketch of Variation XIII documents that the original title was written as three Xs in blue pencil followed by “Var.” (an abbreviation of Variation) in black ink and a large capital L in blue pencil. Remarkably, the original title presents a reverse acrostic of “LVX” which is the classical Latin realization of “LUX.”

The inclusion of the absent L from the title of Variation XIII permits the spelling of the next word from Longfellow’s Cross, LEX. The l from Finale would also suffice for this purpose. Lex is the Latin word for “Law.” In Matthew 5:17, Jesus taught that he came not to abolish the law, but to fulfill it.

The final word from Longfellow’s Cross is LVX. This word is enciphered by the absent L for Variation XIII paired with the first and third Roman numerals from Variation XIV. The X could also be provided by the first Roman numeral from XIII, permitting a phonetic spelling as LX.

The alternate spelling of LVX as LUX is also possible using the absent L from Variation XIII and the U and X from Variation XIV (E. D. U.).

Elgar was an expert in cryptography when he composed the Enigma Variations between October 1898 and July 1899. Consequently, the discovery of a cornucopia of ciphers within that breakout symphonic work is consistent with Elgar’s psychological profile. Elgar’s mother imbued him with a deep and lasting respect for Longfellow’s artistic vision that merged German romanticism with Christianity. Elgar melded his artistic output with Longfellow’s poetry in a string of works produced between 1892 and 1903. At the conclusion of the extended Finale to the Enigma Variations, Elgar cites a passage from Longfellow’s poem Elegiac Verse. He wrote, “Great is the art of beginning, but greater the art is of ending.” With this quotation at the end of the Variations, Elgar suggests that other Longfellowian elements are lurking in that particular area of the score. An analysis of proximate title letters reveals that four Latin words from Longfellow’s Greek Cross in The Golden Legend are enciphered by Variations XIII and XIV. This discovery is part of a larger pattern of coded references to the cross in the Enigma Variations.

The ciphers of the Enigma Variations encode a discrete set of answers that identify the covert Theme, the Enigma’s “dark saying,” and the secret friend of Variation XIII. The discovery of any of these cryptograms in isolation could be comfortably written off as a coincidence. However, their sheer number cannot be conveniently passed off to chance or confirmation bias, particularly as they encode a small set of interlocking answers. These ciphers betray a grand design and affirm Elgar’s genius for cryptography. To learn more about the innermost secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elar's Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please post your comments.