|

| Oedipus and the Sphinx by Ehrmann |

“En arca abierta el justo peca.”(The righteous sins in an open chest)

Spanish Proverb

The British composer Edward Elgar (1857–1934) and his wife enjoyed a brief stay in July 1897 with the family of Reverend Alfred Penny (1845–1934), the rector of St. Peter’s Collegiate Church in Wolverhampton. Caroline Alice Elgar (1848–1920) was a childhood friend of the Reverend’s wife, Mary Frances Baker, who married the widower in 1895 and became the stepmother of his only daughter, Dora Penny (1874–1964). On their return to Great Malvern, Alice penned a letter thanking the Penny family for their hospitality. Elgar added a short enciphered missive to his wife’s correspondence, addressing it to “Miss Penny” on the verso. The incisive salutation is a classic Elgarian pun. While “Miss” is an honorific title for an unmarried woman or girl, it also functions as the verb “miss” to express regret or sadness over a person’s absence. Elgar was clearly missing Miss Penny when he created his cryptographic pièce de résistance. Dora was unable to decipher Elgar’s enigmatic script and filed it away for forty years before eventually publishing it in her 1937 biography.

Elgar’s coded message to Dora Penny is popularly referred to as the Dorabella Cipher. The name comes from Variation X of the Enigma Variations (1899), a movement dedicated to her that bears the title “Dorabella.” Elgar derived that playful pseudonym from a soprano role for a young unmarried woman in the opera Così fan tutte by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. An operettic nickname for Dora was befitting because she was an avid vocalist who sang in the Wolverhampton Choir Society and her father’s rectory choir. As she recalled in her biography, “I was so mixed up with tunes in those days; Choral music, Church music, and orchestral music – and my own solo-singing, scenes from opera, songs, ballads –, and so on.”

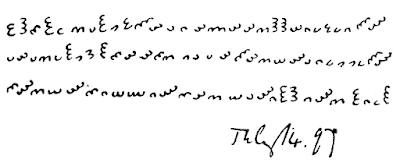

The Dorabella Cipher has 87 curlicue symbols arranged in three rows of varying uneven character lengths followed by a fourth row giving the date “July 14 [18]97”. There are 29 characters in row one, 31 in row two, 27 in row three, and 8 in row four. A small dot appears over the sixth symbol in row three. Three other dots appear in row four. Small dots are placed to the right of the “1” and “4”, and a larger dot is affixed to the bend in the “7”. In all, there are 87 symbols, four rows, four dots, four letters, and four numbers on the Dorabella Cipher.

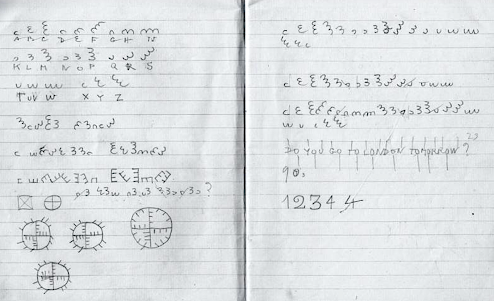

The key for translating this confounding cast of characters into recognizable cleartext is conveniently preserved in one of Elgar’s surviving notebooks. A facsimile of that cipher key is displayed below:

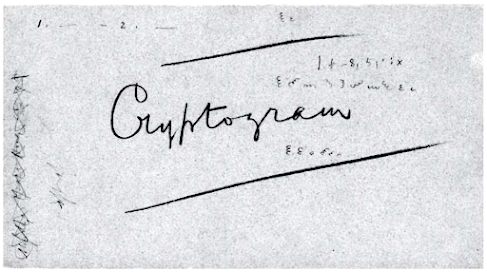

Elgar sketched three distinct glyphs using the lower case c as the primary building block. His motive for selecting that particular letter is easy to surmise because c is the initial for cipher and cryptogram. There is circumstantial evidence in support of this hypothesis as Elgar wrote some of these same symbols around the word “Cryptogram” on an index card dating from 1896.

With his three prototypes assembled from one, two, and three cs layered atop another, Elgar systematically arranged them into eight different triplets using various angles and orientations to generate 24 alphabetic avatars. Elgar assigned the alphabet’s 26 letters to these 24 odd characters by merging i with j and u with v. Conflating similar letters is a standard convention in cryptography. The resemblance of some of Elgar's curlicue characters to the capital cursive “E” from his initials is deliberate, embellishing the cipher with his imprimatur in contrasting guises. Relying on Elgar’s notebook key, the Dorabella Cipher converts into the following cleartext:

Elgar used twenty symbols from his twenty-four character cipher alphabet, omitting those for M, N, O, and Z. The three contiguous absent letters (M, N, O) are an anagram of nom which means “name.” This word appears in the expression nom de plume which refers to a pseudonym or pen name. Elgar’s signature is conspicuously absent from his coded missive. Could the anagram nom sourced from these missing letters be a clue that Elgar’s name is hidden within the ciphertext? The absence of these four letters parallels the structural emphasis placed on that number by four rows, four dots, four letters, and four numbers. Elgar is clearly hinting at the importance of the number four. The reason could be that the fourth letter of the alphabet is D, the initial for Dora.

Cryptographers are baffled by the Dorabella Cipher’s seemingly incoherent hodgepodge of nonsensical letters. In his history of unbroken cryptograms entitled Unsolved!, mathematics professor Craig P. Bauer concedes that the Dorabella Cipher appears to be a simple monoalphabetic substitution cipher (MASC) in which one letter is replaced by one symbol. Gaps between words are excised to make the code more difficult to unravel. Like modern ciphers, ancient Greek and Classical Latin text omit spaces between words in a practice labeled scriptio continua. Bauer laments that when applied to the Dorabella Cipher, none of the standard techniques for solving a MASC yield sensible or credible results. Even the most advanced computer programs fail to make any inroads.

Bauer briefly describes and dismisses purported solutions by Eric Sams, Tony Gaffney, and Tim S. Roberts. He rightly concludes the Dorabella Cipher has not yet been solved because Elgar’s system of encipherment must be “something more complicated.” In his 2023 paper Dorabella unMASCed published in the journal Cryptologia, Viktor Wase demonstrates that state-of-the-art algorithms are capable of solving an 87-character MASC with a success rate of 98.7% in English and 98.6% in Latin. When these advanced algorithms are deployed against the Dorabella Cipher, they fail to generate any meaningful decryptions. These advanced algorithms are unable to brute force the Dorabella Cipher, effectively ruling out a basic MASC in English or Latin. This approach presumes that the message is not obscured by nonsense text strings.

Elgar was a rational and creative innovator. He was also an accomplished musician, a profession that requires a familiarity with multiple languages such as Italian, German, and French. His correspondence evinces an affinity for inventive phonetic spellings and neologisms. One should reasonably expect he would construct an innovative cipher that draws on these skill sets to foil decryption. One such complication could be the use of more than one language. Another twist would be the introduction of some phonetic spellings. The presumption Elgar would simplistically design the Dorabella Cipher as a MASC framed in one language induces an analytical tunnel vision that impairs all decryption attempts. This readily explains why all attempts at brute-forcing it end in futility, prompting some to resort to contorted purported solutions. Elgar deliberately designed his cipher to give the appearance of a MASC to serve as a mask that conceals a more nuanced mode of encryption. A great cryptographer excels at misdirection and deception.

There is ample evidence that Elgar employed numerous languages to complicate some of his cryptograms. The most compelling illustration is a musical Polybius cipher enclosed within the opening six bars of the Enigma Theme. Rather than predictably relying on only his native language, he deployed a combination of four languages to formulate the full decryption: English, Latin, German, and what he would have reasonably believed to be Aramaic (but turns out to be Hebrew). Incredibly, these four languages are an acrostic anagram of ELGAR.

- English

- Latin

- German

- Aramaic

Realizing it would be contested, the solution stealthily unveils Elgar’s signature using another tier of encryption involving anagrammitization. Elgar was fond of anagrams. When he moved his family to a new home in March 1899, he christened the residence Craeg Lea. He devised that unusual title by reversing the letters of his last name (Craeg Lea) and inserting the initials from the first names of his wife Alice (Craeg Lea), daughter Carice (Craeg Lea), and himself (Craeg Lea). His musical Polybius cipher was produced a little over a year after he sent his encrypted message to Dora Penny. The close timing between these ciphers bolsters the hunch that he may have applied similar techniques in both of them.

When Elgar solved a challenge cipher by John Holt Schooling in 1896, he meticulously documented his solution on a set of nine index cards. On one of those cards, he wrote the word “Cryptogram” in large thick letters accompanied by eighteen symbols from the same cipher alphabet used on the Dorabella Cipher. The discrete symbols represent twelve letters: B, C, D, F, I/J, M, P, S, W, X, and Z. The B and C symbols each appear thrice, and the X symbol twice. Similar to the Dorabella Cipher, the symbols are arranged into three rows of varying lengths.

Elgar employed some unusual phonetic spellings in his correspondence. For example, he respelled phrases as “frazes,” gorgeous as “gorjus,” and excuse as “xqqq.” Bearing this in mind, consider that the cipher symbols on the “Cryptogram” index card encode the letters “BX” twice. “BX” is a phonetic spelling of box. The first is situated at the end of the second line of ciphertext. The second is near the start of the third row of characters that begins with “CBX”. This second instance is intriguing as it may be read phonetically as “See Box.” This reading is credible because Schooling’s allegedly unbreakable code was a Nihilist cipher, a variant of the Polybius square. It is distinctly plausible that the Dorabella Cipher is encoded in numerous languages using fractionated plaintext represented by multiple symbols. This would explain why frequency analysis — a tried and true technique for cracking MASCs — has consistently failed to unlock the contents of Elgar’s coded message. Tracking frequencies of single letters is a dead end.

Recent cryptanalysis of the seemingly impregnable Dorabella Cipher determined that its dotted symbols encode solutions in Latin (AMDG) and German (Magd). Elgar prominently penned the Latin abbreviation “AMDG” on some of his master scores as a sacred dedication. Used to refer to a young unmarried woman, the German word Magd means “maid” and “virgin”. This solution matches with the recipient of Elgar’s coded missive, Miss Dora Penny, the young unmarried daughter of Reverend Penny. The Dorabella Cipher also presents some English words as the note is addressed to “Miss Penny” and the date includes the month “July”. Remarkably, these three languages — English, Latin, and German — are an acrostic anagram of the first three letters of ELGAR. The linguistic sophistication of the Dorabella Cipher easily explains why experts failed to unravel it since they naively assumed it was restricted to English. Such a unidimensional mindset is utterly incompatible with an autodidactic polymath like Elgar.

Three of the four absent letters (M, N, O, Z) from the Dorabella Cipher are an anagram of nom, a synonym for name. Remarkably, the dot above the sixth character in row three of the Dorabella Cipher pinpoints a familiar nickname for Elgar. Relying on Elgar’s notebook key, the raw decryption of the character below the dot in row three is the letter E. A single dot in International Morse Code is also E. Consequently, the dot and the symbol encode Elgar’s initials (EE). Immediately following the encoded E, the next two characters encode the letters D and U/V. Remarkably, the small dot above the ciphertext in the third row tags the text sequence “E D U”.

“Edoo” is a pet name for Elgar coined by his wife. She conceived of this pseudonym using the first three letters of the German version of her husband’s forename, Eduard. Elgar assigned this nickname to his musical self-portrait in the Enigma Variations (1899), the martial Finale with the title “E. D. U.” Dora Penny was familiar with this pet name as she spent a substantial amount of time around the Elgar family and heard Alice call her husband “Edoo.” This fragmentary decryption confirms that the Dorabella Dots Dedication Cipher is covertly signed by its author. The solution is consistent with the feasibility of spelling nom from absent letters in the cipher and the glaring absence of Elgar’s signature from his note. The discovery of Elgar’s nickname is consistent with other cryptograms in the Enigma Variations that are similarly tagged by his name or initials.

Far from being a random assortment of letters as posited by cryptanalysts like Keith Massey, the cleartext presents a coded form of Elgar's name expertly spliced into the fabric of the cleartext. Elgar made it an obvious place to look because of the anomalous dot above the sixth character in row three. This “EDU” Dot Cipher furnishes the author's signature conspicuously missing from his missive to Miss Penny. It is astonishing that this signature remained undetected since the cipher was first publicized 75 years ago in 1947. One reasonably wonders what else the so-called experts failed to detect lurking just beneath the surface of the Dorabella Cipher. To be blunt, Elgar's encoded signature was not difficult to spot.

A polyglot Polybius cipher ensconced within the opening measures of the Enigma Theme utilizes four languages in its complete decryption: English, Latin, German, and Aramaic. Elgar devised this elaborate cryptogram a little over a year after the Dorabella Cipher. My original research confirms that the Dorabella Cipher employs three of those same languages found in the musical Polybius cipher: English, Latin, and German. The linguistic parallels between these two cryptograms imply that the Dorabella Cipher may include yet another language. Could there be a fourth language in the Dorabella Cipher just as there is in the Enigma Theme’s Polybius Cipher?

The cleartext of the Dorabella Cipher appears to be a nonsensical array of letters. With such a cipher, however, appearances are designed to be deceiving. The unmasking of Elgar’s pseudonym starting at the dotted symbol in row three disproves that misimpression. On closer review, the cleartext was found to contain eleven discrete Spanish words with some overlaps and duplications. I was able to pick out these words with the assistance of my daughter Grace who is fluent en español. These Spanish terms are highlighted in yellow within the Dorabella Cipher cleartext in the table below:

Eleven Spanish words are detectable in the Dorabella cleartext using 22 out o 87 characters representing 25% of the cryptogram. Symbols 2-5 in row one encode peca, the first Spanish word to surface within the cleartext. Peca means “freckle” and “spot.” The latter translation is notable because there is a smattering of four dots resembling spots on the Dorabella Cipher. The first and only spot found among the ciphertext is placed above the sixth character in row three. As mentioned earlier, that anomalous spot marks exactly where the cleartext spells out Elgar’s German pseudonym (EDU). The errant dot tells us where to spot something important, namely Elgar’s name conspicuously absent from his note. This extraordinary find verifies the Spanish word peca is connected organically to the cipher’s unusual construction and cleartext.

Elgar’s pet name was invented by his wife, Caroline Alice Elgar. Remarkably, peca contains her initials because its latter three letters (eca) form a proximate letters anagram of “CAE”. Alice was fluent in Spanish and evidently assisted her husband with the selection and spelling of these Spanish words in the cleartext. The spot that links Elgar’s pet name in row three with peca in row one presents a coded link with his wife’s initials that form most of that first recognizable Spanish term.

Besides meaning “freckle” and “spot,” peca can also denote “sin” The Spanish proverb “En arca abierta el justo peca” is one example. The literal translation is, “The just man sins in an open chest.” The saying implies that even a good person can be tempted to steal from an open treasure chest. The English equivalent is, “Opportunity makes the thief.” This Spanish aphorism is fascinating because arca can be translated as “box.” It is plausible Elgar used peca to hint at that Spanish proverb, and indirectly to the nature of his Polybius cipher. The Spanish expression, “Darle por donde peca” (Give him where he sins) also uses peca in the same way. In both examples, the word peca means sin. As the daughter of an Anglican rector, Dora was familiar with the theological ramifications of sin. Her father preached often on the necessity of Christ’s atonement for sin, a message at the crux of Roman Catholic and Protestant traditions.

Symbols 10 and 25 are y, the Spanish word for “and.” The pronunciation of y is a homophone of the letter e. Consequently, two ys in the first row present a coded form of Elgar’s initials (EE). Symbols 16-17 in row one encode the second Spanish term ir, the verb “go.” The combination of peca with ir in the first row suggests the phrase “Go [to the] spot.” This combination of Spanish terms in the first row directs us to the spotted character in row three where Elgar’s pet name is encoded. This means that the appearance of peca and ir in row one cannot be casually chalked up to happenstance. Their specificity and proximity within the same row affirm a sophisticated design.

Symbols 38-42 in the second row encode the third Spanish word, cerré. The definition of cerré is, “I closed.” Its position gives away the issuer of that statement as the symbols for cerré align and overlap with those in row three that form Elgar’s nickname. In this coded manner, Elgar declares he “closed” up the meaning of his message via a cipher. Schooling deploys the same language to characterize his Nihilist challenge cipher. He writes, “The ‘box,’ which for us has been unlocked to let out the cipher secrets of past centuries, is now closed and firmly shut its fastenings for one hundred years of future time.” This semantic parallel with Elgar’s Spanish declaration “I closed” is further circumstantial evidence for a Polybius-style mode of encipherment. It is conceivable Elgar summed the serial numbers of his symbols in pairs to generate a Nihilist cipher. Further research and analysis are required to assess that possibility.

The last symbol of row two and the first of row three (Symbols 60-61) spell the fourth Spanish word se which means “I know.” That same term is repeated two more times in row three by symbols 65-66 and 71-72. Following Elgar’s declaration that he “closed” his cryptogram, he reiterates that he “knows” the solution in three short declarations within the cleartext. This relationship is established by the second se as its e provides the first letter of Elgar’s nickname. Similarly, the third se overlaps with the fifth and final Spanish word in the cleartext, ser which means “to be” formed by symbols 71-73. The glyph for the numeral “3” is the mirror image of Elgar’s capital cursive “E.” Symbols 61-62 spell es, the third person singular of ser which translates as is. Symbols 65-67 spell sed, the Spanish word for “thirst.” Two of the letters from sed overlap with Elgar's pet name (Edu). This overlap highlights an abbreviated version of Elgar's forename as “Ed.” The convergence of Elgar's pet name and first name with the Spanish word for thirst intimates that he thirsts for Dora Penny's refreshing company.

The presence of these Spanish words in the cleartext could be connected to Spanish proverbs, but this is admittedly an interpolation. There is an old Spanish proverb, “Ser mucho cuento”, that literally translates as, “To be a lot of stories.” This idiom refers to something that requires much thought and reflection. That would be an apt way to describe a cryptogram that conceals a message. Another Spanish proverb that ends with the word ser is, “Amar, e saber naõ pode ser.” The literal translation reads, “To love, and to know nothing can be.” The English equivalent is, “To love and be wise is incompatible.”

Elgar showed an interest in Spanish subjects in some of his early compositions. He composed Sevillaña (Scène Espagnole) in 1884, a short work for orchestra published by Tuckwood as his Op. 7. That opus number followed by a period is reminiscent of the dotted “7” in the date row of the Dorabella Cipher. The initials for Scène Espagnole (SE) appear as the Spanish word se in three different places of the Dorabella Cipher's cleartext. Eight years after completing Sevillaña, Elgar composed a work for choir and small orchestra in 1892 called Spanish Serenade Op. 23. That opus number matches Dora Penny’s age when Elgar penned the Dorabella Cipher. The libretto was sourced from Act I Scene 3 of The Spanish Student by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), one of Elgar’s favorite muses whose prose populates the lyrics for The Black Knight (1893) and Scenes from the Saga of King Olaf (1896). In his brief introduction, Longfellow acknowledges the literary antecedents for The Spanish Student:

The subject of the following play is taken in part from the beautiful tale of Cervantes, La Gitanilla. To this source, however, I am indebted for the main incident only, the love of a Spanish student for a Gypsy Girl, and the name of the heroine, Preciosa. I have not followed the story in any of its details.

In April 1899, Dora Penny attended a performance of The Spanish Student by the Worcestshire Philharmonic Society conducted by Elgar. He may have inserted Spanish terms into the Dorabella cleartext to allude to these earlier compositions, perhaps as a clue regarding a particular password for a Nihilist cipher.

A meticulous study of the Dorabella Cipher’s cleartext confirms it harbors eight discrete Spanish words (peca, y, ir, cerré, se, es, sed, ser) with a total of eleven occurrences with se repeated three times. One is a conjunction (y), one is a noun (peca), and six are verbs (ir, cerré, se, es, sed, ser). All of these Spanish terms are spelled correctly and occupy 21 out of 87 symbols for just over 24 percent of the ciphertext. The noun peca means “spot” and directs attention to the dotted character in row three where Elgar’s pet name “EDU” is encoded. The verb cerré translates as “I closed,” a statement that is easily related to sealing shut a message with cryptography. Incidentally, cerré is related to encerrada that appears in Elgar's cryptic Spanish dedication to his Violin Concerto in B minor. The verb se means “I know”, and in this context reflects Elgar’s unique knowledge of the full decryption. The number, accurate spellings, and relevant meanings of these seven distinct Spanish terms sprinkled throughout the Dorabella Cipher’s cleartext decisively rule out a random origin.

The discovery of Spanish terms in the Dorabella Cipher’s cleartext brings Elgar’s tally of tongues to four: English, German, Latin, and Spanish. The selection of these four languages may have been motivated by their association with operas. There is a rich history of English, German, and Spanish opera. A formative influence on Elgar’s compositions was the German composer Richard Wagner whose operas dominated the opera houses during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Although Spanish opera failed to enter the international repertoire, one of the most wildly popular operas of all time is Carmen, a Spanish-themed drama based in Seville. Only a handful of operas are written in Latin. For example, Mozart’s first opera, Apollo et Hyacinthus, has a Latin libretto.

With his Enigma Theme Polybius Cipher, Elgar used four languages to produce an acrostic anagram of ELGAR. A similar tact is observed with the four detectable languages in the Dorabella Cipher:

- Latin

- English

- German

- Spanish

The first letters of these four languages generate the acrostic anagram “LEGS.” What could be Elgar’s motivation for encoding “legs” in the Dorabella Cipher? His secret message was directed to a young unmarried lady, so some may be tempted to misattribute it to some indecorous intent. This view is untenable as Elgar’s wife obviously assisted him with the Spanish bits of the cipher and was undoubtedly privy to his message. During that mid-July visit, Elgar performed on the piano various excerpts from Lux Christi, Scenes from the Bavarian Highlands, and other works. Dora was so moved by his compositions that she began to dance spontaneously. Therefore, an acrostic anagram of “LEGS” formed by the four languages in the Dorabella Cipher could be in deference to Dora’s proclivity to dance along to Elgar’s music.

Another credible explanation for the linguistic anagram “LEGS” is suggested by an event from Greek mythology. Why consider that esoteric subject area? Elgar was nicknamed “Sphinx” by August Jaeger, his friend at Novello who is so nobly depicted in Variation IX (Nimrod). There is a famous riddle about legs posed by the Sphinx of Thebes to Oedipus. As recorded in Bibliotheca by Apollodorus, the riddle goes, “What is that which has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?” The similarity between the name “Dora” and the latter part of “Apollodorus” is tantalizing. Oedipus correctly answered the Sphinx’s enigma by replying that the mysterious creature with one voice was man because he crawled on all fours as an infant, walked on two legs in his maturity, and used a walking stick in old age. Gustave Moreau brilliantly captures this encounter in his 1864 painting Oedipus and the Sphinx. That renowned painting visually portrays a meeting between the masculine and the feminine. The “legs” acrostic anagram could be a clue regarding a keyword for a Nihilist cipher. Further cryptanalysis is needed to evaluate that prospect.

The second letters of the Dorabell Cipher’s four languages form a mesostich of the Spanish word pena. A mesostich is an acrostic produced by middle letters.

This outcome could be construed as fortuitous except for two glaring reasons. First, there are eight discrete Spanish terms in the cleartext. Second, one of those terms (peca) is extremely similar to pena, sharing two of the same letters in the first (p) and fourth (a) positions. Consequently, the Spanish mesostich pena can be reasonably deduced as deliberate. Depending on the context, pena may be defined as penalty, pain, sorrow, trouble, distress, embarrassment, heartache, misery, infliction, forfeit, labor, and fash. These uniformly negative definitions are consistent with the fate of those who fail to answer the Sphinx’s riddle about legs.

Possible mesostich anagrams from these four cipher languages are tigre (tiger) in columns 2-4, alas (wings) in columns 2-6, and ninã (little girl) in columns 4-6.

The fusion of feline, avian, and feminine solutions is remarkable because the sphinx has the body of a lion, the wings of a bird, and the upper torso and head of a woman. This chimeric creature is famously depicted in paintings by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Gustave Moreau. It is exceedingly unlikely that all of these interrelated Spanish terms associated with the sphinx could be randomly assembled from Elgar’s lingual quadplex. This is especially the case as he scrupulously initialed his cryptogram (EE) with two contiguous Es.

For those who doubt whether Elgar could construct such an elaborate cryptogram, consider that it is also feasible to spell his name as a mesostich anagram from letters in columns 1-3, and a second time in columns 2-4. In a cunning display of cryptographic prowess, he autographed his lingual quadplex.

Far from being a simple monoalphabetic substitution cipher restricted to the English language, the Dorabella Cipher is actually a multilayered polyglot cryptogram. To learn more about Elgar’s obsession with cryptography, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

|

| L'Enigme (The Enigma) by Ferdinand Faivre. |

No comments:

Post a Comment