Elgar made it perfectly clear to us when the work was being written that the Enigma was concerned with a tune, and the notion that it could be anything other than a tune is relatively modern. I am sure that E.E. would not have expected me to guess it if it had been an idea and not a tune. I was so mixed up with tunes in those days; Choral music, Church music, and orchestral music — then my own solo-singing, scenes from opera, songs, ballads —, and so on. How I went through them all in my mind, trying to think of airs written in the same tempo and rhythm as the Enigma, and wondering which ones I had spoken to E.E. or which he would think were connected specially with me or my work or occupations. I almost lay awake at night thinking and puzzling, and all to no purpose whatever. It was annoying! And most annoying of all was one day, on a visit to Malvern, when I simply begged him to tell me what it was. I suggested all sorts of tunes trying to see if I could get a rise out of him, or even a hint, and he looked at me in a sort of half-impatient, half-exasperated way and snapped his fingers, as though waiting for me to think of the tune there and then. I always feel, on looking back to that moment, that he was on the point of telling me what it was, and then he just said:‘I shan’t tell you. You must find it out for yourself.’

Dora Powell (née Penny) in Edward Elgar: Memories of a Variation

Call to Me, and I will answer you, and show you great and mighty things, which you do not know.

Jeremiah 33:3 from the New King James Version

The English composer Edward Elgar excelled at cryptography, the science of coding and decoding secret messages. His obsession with ciphers merits an entire chapter in Craig P. Bauer’s book Unsolved! Bauer devotes much of the third chapter to Elgar’s meticulous decryption of a purportedly insoluble Nihilist cipher released by John Holt Schooling in the April 1896 issue of The Pall Mall Magazine. A Nihilist cipher is built on a Polybius square key. Elgar was so gratified by his decryption of Schooling’s impenetrable code that he mentions it in his first biography released by Robert J. Buckley in 1905. Elgar painted his solution in black paint on a wooden box, an appropriate medium as another name for the Polybius square is a box cipher.

Elgar’s meticulous decryption of Schooling’s cryptogram is summarized on a set of nine index cards. On the sixth card, Elgar likens the process to “. . . working (in the dark).” Note his use of the word dark as a synonym for cipher.

Elgar’s parenthetical remark is revealing as he employs that same language in the original 1899 program note to describe the Enigma Theme. It is an oft-cited passage that warrants revisiting as he lays the groundwork for his tripartite riddle:

The Enigma I will not explain–its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the connexion between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’, but is not played . . . So the principal Theme never appears, even as in some later dramas–e.g., Maeterlinck’s ‘L’Intruse’ and ‘Les sept Princesses’–the chief character is never on the stage.

Elgar wields the words dark and secret interchangeably in a letter to August Jaeger penned on February 5, 1900. He wrote, “Well—I can’t help it but I hate continually saying ‘Keep it dark’—‘a dead secret’—& so forth.” One definition of dark is “secret.” A saying is a series of words that generate a coherent phrase or adage. Based on these definitions, Elgar’s odd expression—“dark saying”—may be interpolated as coded language for a cipher. In a roundabout way, Elgar hints that the Enigma Theme conceals a secret message.

Mainstream scholars insist there are no valid solutions to the Enigma Variation because Elgar allegedly concocted the notion of an absent principal Theme as an afterthought, practical joke, or marketing ploy. The editors of the Elgar Complete Edition preemptively reject the likelihood of any stealthy counterpoints or cryptograms. Relying on Elgar’s recollection of playing new material at the piano to gauge his wife’s reaction, they tout the standard lore that he must have extemporized the idiosyncratic Enigma Theme mirabelle dictu without any forethought or planning:

There seems to have been no specific ‘enigma’ in mind at the outset: Elgar’s first playing of the music was hardly more than a running over the keys to aid relaxation. It was Alice Elgar’s interruption, apparently, that called him to attention and helped to identify the phrases which were to become the ‘Enigma’ theme. This suggests it is unlikely that the theme should conceal some counterpoint or cipher needed to solve the ‘Enigma’.

Their thesis is laden with nebulous terms like seems, apparently, suggests, and unlikely. Such a blanket renunciation conveniently relieves musicologists of any duty to probe for counterpoints and ciphers. Prominent offenders include such luminaries as Robert Anderson, Jerrold Northrop Moore, and Julian Rushton. The ignominious irony is that proponents of such a stark denialism extol the validity of their position based on a dearth of evidence for which they never executed a diligent or impartial search. Such a ridiculous state of affairs is a textbook case of confirmation bias pawned off as “scholarship.” Carl Sagan warns against that perilous persuasion with the antimetabole, “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

The more sensible view (embraced by those who take Elgar at his published word) accepts the challenge that there is a famous melody lurking behind the Variations’ contrapuntal and modal facade. In his sanctioned 1904 biography, Elgar plainly states, “The theme is a counterpoint on some well-known melody which is never heard . . .” Most scholars insist the answer can never be known for certain because Elgar allegedly took his secret to the grave. This supposition precludes from consideration the possibility that he encoded the solution within the Enigma Variations for posterity to discover. Indeed, such a rigid judgment glosses over or blatantly ignores Elgar’s obsession with cryptography. That incontestable facet of his psychological profile enhances the possibility that solutions are skillfully encoded by the Enigma Variations’ orchestral score.

A compulsion for cryptography is a reigning facet of Elgar’s personality. Trawling the Enigma Variations for over a decade netted over one hundred cryptograms in diverse formats that encode a set of mutually consistent and complementary solutions. Although that sum may seem extraordinary, it is entirely consistent with Elgar’s fascination for ciphers. Solutions encoded by these cryptograms answer the riddles posed by the Enigma Variations. What is the secret melody to which the Enigma Theme is a counterpoint and serves as the melodic foundation for the ensuing movements? Answer: Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) by the German reformer Martin Luther. What is Elgar’s “dark saying” concealed within the Enigma Theme? Answer: A musical Polybius cipher situated in the opening six bars. Who is the secret friend and inspiration behind Variation XIII? Answer: Jesus Christ, the Lord and Savior of Elgar’s Roman Catholic faith.

Elgar’s “Enigma Day” Wordplay

On 21 October 1898, Elgar penned a letter to F. G. Edwards, the editor of The Musical Times. In his missive, Elgar mentions a symphonic project in honor of General Gordon who died thirteen years earlier at the Siege of Khartoum. The English public revered Gordon as a crusading Christian martyr for refusing to surrender the city to Mahdist forces or convert to Islam to preserve his life. Queen Victoria grieved his tragic death and displayed Gordon’s tattered pocket Bible in an ornate crystal display case in the Grand Corridor of Windsor Castle. Elgar wrote to Edwards, “Anyhow ‘Gordon’ simmereth mighty pleasantly on my (brain) pan & will no doubt boil over one day.” Later that same evening, Elgar played the Enigma Theme for the first time on the piano for his wife. After hearing that melancholic melody, Alice inquired with an approving tone, “What is that?” He replied, “Nothing—but something might be made of it.” The private premiere of the Enigma Theme on that pivotal evening is commemorated by Elgarians every October 21 as Enigma Day. This October 21st marks the 126th anniversary of “Enigma” Day, a pivotal moment that transpired a little over 46,000 days ago.

Elgar’s documented uses of the words mighty and might on 21 October 1898 are a clever Enigma Day wordplay. Exhaustive research implicates the Lutheran hymn Ein feste Burg as the covert Theme to the Enigma Variations. The most prevalent English translation of that title by Frederick H. Hedge is A Mighty Fortress. The central word of that renowned title is mighty, the same employed in Elgar’s letter to Edwards on Enigma Day. Elgar also conspicuously used the word might when describing the Enigma Theme later that same evening. When Elgar used the words mighty and might on Enigma Day, it is conceivable that he did so to hint at the title of the secret melody underlying the Enigma Variations.

Elgar was seriously contemplating a symphony about General Gordon whose storied career was distinguished by the capture and defense of numerous fortifications. In his famous last stand, Gordon transformed the city of Khartoum into a veritable fortress that withstood a ten-month siege before falling to Mahdist forces in January 1885. This recurring theme in his professional life furnishes a distinct association between Gordon and fortresses. Consequently, it is not a quantum leap to associate Gordon with the word fortress. From this perspective, Elgar’s description of his Gordon symphony as “mighty” may be interpolated as a subtle wordplay on a “Mighty Fortress.”

In early September 1898, General Kitchener recaptured Khartoum and held a memorial service for General Gordon in front of the palace where he fell in battle. That event made international news only a month before Elgar began working in earnest on the Enigma Variations. It is conceivable Elgar experimented with Ein feste Burg as a prospective foundational theme for his Gordon Symphony because of its martial associations and Gordon’s mystical Protestant faith. Elgar had a penchant for penning counterpoints to famous melodies. As a proud Roman Catholic, it would make sense for him to cloak a Protestant anthem with a contrapuntal analog because Luther was a renegade priest excommunicated for heresy. Elgar advised in his 1905 biography that the Enigma Theme “. . . is a counterpoint on some well-known melody which is never heard . . .” What likely transpired on Enigma Day is that Elgar’s counterpoint to Ein feste Burg refracted his Gordon Symphony into a series of orchestral variations about his predominantly Anglican friends and fellow admirers of Gordon.

The “EFB” Titles Ciphers

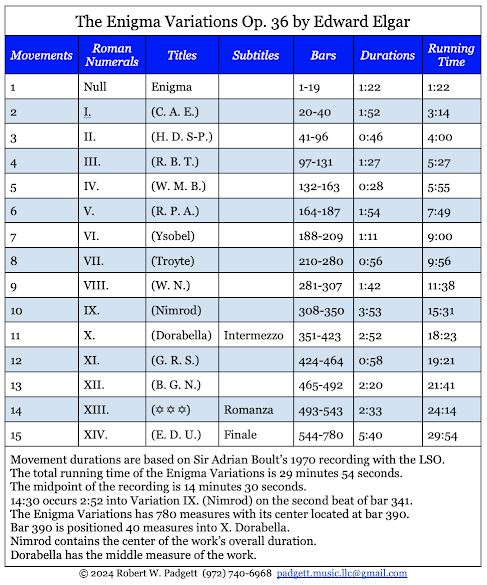

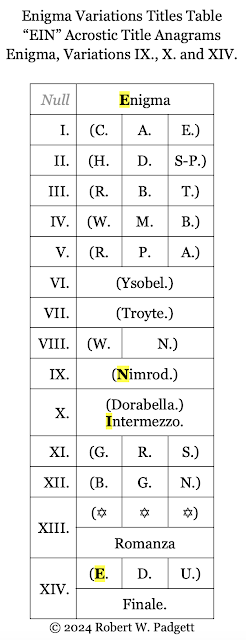

On the eve of the 126th anniversary of “Enigma” Day, it is exciting to announce the discovery of another cryptogram ensconced within the titles of the Enigma Variations. This cipher employs four titles to generate two acrostic anagrams of “EIN”, the first word of the covert Theme’s title. The first is the title of the Theme (Enigma). The second is the nickname for Jaeger allotted to Variation IX (Nimrod). The third is the subtitle “Intermezzo” attached to Variation X (Dorabella). The fourth is the nickname “E.D.U.” (Edoo) given to Elgar’s musical self-portrait, Variation XIV. These four titles—Enigma, Nimrod, and Intermezzo, and E.D.U.—yield two iterations of “EIN” as acrostic anagrams. The first is obtained from the Theme, Variation IX and X. These movements disclose an acrostic of “EIN” when ordered as the Theme, Variation X and IX.

- Enigma

- Intermezzo

- Nimrod

The second is sourced from Variation XIV, Variation X, and IX. These movements produce an acrostic of “EIN” when arranged in reverse order as Variation XIV, X, and IX.

- E. D. U.

- Intermezzo

- Nimrod

The ability to generate two acrostic anagrams of “EIN” is far from the only reason for classifying movements one, ten, eleven, and fifteen as a discrete subgroup. The first and final movements possess the only titles beginning with E—Enigma and E.D.U. Pairing these outermost movements is supported by the realization that their initials yield an acrostic of Elgar’s initials (EE). As the first and final movements, they envelop and bookend the Enigma Variations. Friends and family routinely referred to Elgar by his initials as illustrated by the quotation from Dora’s memoir in the epigraph.

The first initials and keys of these peripheral movements correspond to the violin’s first and last strings (E-A-D-G). The Enigma Theme is set in G minor, and E.D.U. is framed in G major. The melody of these opening and closing movements is introduced by the first violin section.

The titles of these outer movements consist of six (Enigma) and three (E.D.U.) letters, two sums that may be combined to generate the opus number 36. The number of the letters in the title (E.D.U.) and subtitle (Finale) of Variation XIV also implicate that same opus number. The significance of that opus number is that the reigning consensus at the time Elgar composed the Variations was that Martin Luther composed 36 hymns. In his 1873 book Hymns for the Church and Home, Rev. W. Flemming Stevenson attributes 36 hymns to Martin Luther. Leonard Woolsey Bacon attributes the same number of hymns to Luther in his 1884 book The Hymns of Martin Luther. James F. Lambert itemizes Luther’s 36 hymns in his 1917 book Luther’s Hymns.

There are multiple reasons for grouping variations IX and X together. They are the only two adjacent movements with nicknames as titles. The performance durations of Nimrod (3:54) and Dorabella (2:52) make them the second and third longest movements after the Finale (5:40). Jaeger and Dora were Anglican. Jaeger married Isabella Donkersley on 22 December 1898 at St. Mary’s Abbott’s Church, Kennsington. It is a historic High Anglican parish, indicating that Jaeger and his wife were Protestants who belonged to the Church of England. Dora was the daughter of the Anglican Rector Alfred B. Penny, author of Ten Years in Melanesia about his extended mission to share the Gospel in those distant isles. His obituary published on 15 November 1937 in the Lichfield Mercury heralds him as “A Warrior of the Church.” Dora remained an active member of the Anglican communion throughout her life. In the April 2017 issue of The Elgar Society Journal, Kevin Allen writes that Dora “. . . maintained a lifelong, conscientious Christian faith, participated in all the usual parish doings, and taught a Sunday-School class . . .”

Variations IX and X harbor the written and aural centers of the Enigma Variations. The work consists of 780 bars with the midpoint arriving at measure 390. The central measure is located 40 bars into Dorabella which is four bars after Rehearsal 42. That midpoint is 1 minute 31 seconds into the movement based on Sir Adrian Boult’s 1970 recording of the Enigma Variations with the London Symphony Orchestra. The recording has an overall length of 29 minutes 54 seconds. The exact middle of that highly regarded recording is 14 minutes 57 seconds which lands 2 minutes 56 seconds into Nimrod on the second beat of measure 342 located five measures before Rehearsal 37. The discrepancy of 48 bars between the aural center (bar 342) and middle bar (390) is largely accounted for by a 26 measure repeat of bars 105-130 in Variation III.

The forenames of the dedicatees of movements IX and X are August and Dora. These two names consist of six and four letters, sums that may be combined to yield the anagram 46. That number corresponds to the chapter in the Psalms that inspired Luther to compose Ein feste Burg. The placement of Dora’s variation after the only one dedicated to a native German Protestant is a revealing chronology. The initials of their forenames—A and D—coincide with the two middle strings of the violin (E-A-D-G). These subtle allusions to the middle strings interlock with the First Violin parts that open either movement on the opposing middle string. The First Violins introduce Nimrod’s melody on the D string (sul D) at Rehearsal 33. That cue number is the mirror image of two capital cursive Es, the initials of the composer. Those are the same initials encoded as an acrostic by the titles of the first (Enigma) and last (E.D.U.) movements. Rehearsal 38 marks the beginning of Variation X where the accompaniment played by the First Violins starts on the A string.

Just as Nimrod and Dorabella designate the center of the Enigma Variations, the Theme and the Finale set its outermost boundaries. These beginning and concluding movements further allude to the outer strings of the violin by means of their titles (Enigma and E. D. U.) and parallel key signatures (G minor and G major). There is an autobiographical element to these string references as Elgar taught violin and served as a violinist with William Stockley’s Orchestra and at the Three Choirs Festival. The locations, titles, keys, and violin string references justify the selection of the starting, middle, and ending movements to construct the “EIN” Titles Cipher. The importance of this cryptogram is that it furnishes the first word of the covert Theme’s title.

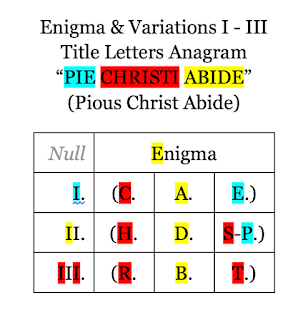

The “EIN” Titles Cipher suggests that the covert Theme’s name is encoded by proximate title letters. It is feasible to assemble “EIN FESTE BURG” from contiguous letters from the titles of XII, XIII, XIV, Enigma, I, II, and III. This cipher spells out the hidden melody’s title starting with the last four movements and finishing up with the opening four movements. This cycling from the end back to the beginning is similar to how Elgar mapped Ein feste Burg in retrograde above the Enigma Theme. The decryption is assembled from eight letters from the last four movements (three from XII and XIV, two from XIII), and four letters from the opening four movements (one letter each from Enigma, I, II, and III). Two movements furnish three letters, a number that mirrors a capital cursive E. Two groups of three letters suggest a coded form of Elgar’s initials, particularly as one of those groups is sourced from his musical self portrait (E.D.U.).

There is a discernable symmetry to this cryptogram as it is constructed from the titles of the last four and opening four movements. This emphasis on the number four parallels how Elgar cites a four-note melodic incipit from a work with a four-word German title on four occasions in Variation XIII. Elgar devised five different lists of the Variations ostensibly to construct this and other proximate title letters anagrams. Another superb example is how adjacent letters from the opening four titles form the Latin and English anagram “PIE CHRISTI ABIDE” (Pious Christ Abide). This decryption is conspicuous as Elgar gave his first sacred oratorio the title Lux Christi Op. 29, a work premiered in 1896 and revised in 1899.

Elgar’s “JOAK” Cipher

The titles needed to produce two acrostic anagrams of “EIN” come from the first tenth, eleventh, and fifteenth movements. The application of an elementary number-to-letter key (1 = A, 2 = B, 3 = C, etc.) converts those movement numbers into the plaintext A, J, K, and O. The first two plaintext letters furnish the initials of August Jaeger. These four plaintext letters are an anagram of “JOAK”, a phonetic spelling of joke. Merriam-Webster defines joke as “something said or done to provoke laughter” and “the humorous or ridiculous element in something.” A joke is a synonym for jape. Elgar used the term “jape” to characterize his earliest surviving musical sketch “tune from Broadheath”. The respelling of joke as “JOAK” is consistent with Elgar’s use of inventive phonetic spellings in his correspondence. For example, he respells phrases as “frazes”, gorgeous as “gorjus”, and excuse as “xqqq”. In his Enigma Variations, Elgar encodes a musical joke with a punchline that begins with Ein. Who would ever suspect that a proud English Roman Catholic would ever select a Lutheran anthem with a German title as the covert theme? The comic irony is acute.

The “joke” decryption is consistent with a second program note about the Enigma Variations that Elgar wrote for the 1911 Turin International Exposition. He penciled this supplementary program note on stationery from the Grand Hôtel Ligure & D’Angleterre. A high-resolution image of the first page is shown below courtesy of the British Library and the joint efforts of Fiona McHenry and Christopher Scobie, Curator of Music Manuscripts. The first line opens with, “This work, commenced in a spirit of humour & continued in deep seriousness, contains sketches of the composer’s friends.”

.jpg) |

| Elgar's handwritten program note (page 1) |

Why would Elgar blend “J” with “OAK” to phonetically spell joke? The oak tree shares multiple associations with Martin Luther. In July 1505 while returning to law school, Luther was caught outside in a thunderstorm. Some accounts claim he sought refuge beneath an oak tree. When lightning struck near him, the blast of the thunder terrified him. In desperation he cried out for help to Saint Anne, the patron saint of miners. He vowed that if she saved him from the raging storm, he would become a monk. A red granite memorial called the Lutherstein (Luther stone) marks the place where Luther abandoned his plan to become an advocate for man and resolved to become an advocate for God. Luther soon joined the Augustinian Monastery in Erfurt and resided in the Lutherzelle, a small room lined with white oak beams.

%20at%20Erfurt%20Augustian%20Monastery.jpg) |

| Lutherzelle (Luther’s Cell) at Erfurt Augustian Monastery |

On 31 October 1517, Luther famously nailed his Ninety-five Theses on the oak door of Schlosskirche (Castle Church). In 1760, the original wooden doors were destroyed in a bombardment by Imperial forces that sparked an inferno that razed Castle Church. Commemorative bronze doors were installed in 1858 on the 373th anniversary of Luther’s birth by order of King Frederick William IV of Prussia. These bronze doors display Luther’s Ninety-five Theses in the original Latin.

|

| Castle Church Commemorative Bronze Doors |

On 10 December 1520, Martin Luther burned the papal bull of excommunication and books by his opponents near a tree known as Luthereiche (Luther’s Oak). It was replanted in 1830 to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Augsburg Confession. In that same year, Felix Mendelssohn premiered his Reformation Symphony for the Augsburg tercentennial celebration announced by King Frederick William III of Prussia. The fourth movement begins with a quotation of Ein feste Burg followed by a set of variations. Four times in Variation XIII Elgar cites a four-note melodic fragment from Mendelssohn’s concert overture Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt (Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage) to hint that Mendelssohn quotes the covert Theme in the fourth movement of another symphonic work. The Mendelssohn quotations in Elgar’s Romanza are critical clues that led to the discovery of Ein feste Burg as the covert Theme.

The Lutherstube (Luther room) at Warburg Castle where Luther hid as a fugitive and translated the Bible into German is lined with oak beams. The Warburg is a medieval castle located in Thuringia. The same oak door that Luther passed through to enter Wartburg Castle is still there today. During his stay, Luther translated the New Testament into German so that the common people could read the scriptures. The oak-lined Lutherstube is considered the birthplace of the written German language.

%20at%20Wartburg%20Castle.webp) |

| Lutherstube (Luther room) at Wartburg Castle |

The Gentleman’s Magazine published in London features the poem “The Protestant Oak” by Henry Brandreth in an 1837 issue. Brandreth’s poem lauds Luther using the symbolism of an oak tree.

The titles from Variations IX and X are an acrostic anagram of “DIN”, a noun defined by Merriam-Webster as “a loud continued noise” and “a welter of discordant sounds.” The Enigma Variations is clearly the antithesis of that definition of din. When defined as a verb, din means “to impress by insistent repetition.” Oxford Languages defines the verb din as to “make (someone) learn or remember something by constant repetition.” Consistent with that definition, the Enigma Variations repeat the Theme over and over again in various guises and contrasting iterations. Some synonyms of the verb din are instill, drill, ingrain, inculcate, and indoctrinate. Luther composed hymns and encouraged congregational singing of his compositions to impart and inculcate theological tenets.

The “EFB BE AFF” Cipher

The key signatures of the first, tenth, eleventh, and fourteenth movements are G minor (Enigma), G major (X and XIV), and E♭ major (IX). The accidentals of those key signatures are B♭, E♭, and F♯ for G minor, F♯ for G major, and B♭, E♭, and A♭for E♭ major. When arranged in alphabetical order, the seven letters of those accidentals become “ABBEEFF”. The seven accidental letters may be reshuffled into the anagram “EFB BE AFF”. What could be the meaning of this seven-letter decryption?

“EFB” is the acronym for Ein feste Burg. The next two letters “BE” is a verb defined by Merriam-Webster as “to equal in meaning” and “have identity with”. “AFF” is the acronym for A Fortress Firm, one of the numerous English translations of Ein feste Burg. A fortress firm is God our Lord by Dr. W. L. Alexander was published by the Scottish Congregation Magazine in January 1859. A Fortress firm and steadfast Rock is another translation by Frances Elizabeth Cox released in 1864. These transitions are itemized in the 1892 edition of A Dictionary of Hymnology edited by John Julian. The anagram “EFB BE AFF” may be read as “Ein feste Burg be A Firm Fortress”. This solecistic decryption succinctly equates two titles that refer to the same work. Elgar’s reliance on initials is consistent with the majority of Enigma Variations which also are assigned initials.

Jaeger’s letter to Dora

The premiere of The Dream of Gerontius took place on 3 October 1900 at Birmingham Town Hall. In a letter to Dora Penny penned eleven days later, Jaeger complained about her absence at the premiere while stressing the pairing of his Variation with her own:

All the Germans I spoke to at B’ham (Richter, Dr Otto Lessman, Prof. Booths, etc. etc.) were enthusiastic about Elgar’s work. Directly it was over Buths grasped hands (coram public) & blurted out ‘Ein Wunderbares Werk; eins der schönsten Werke die ich kenne’ etc. etc. . . To be with Buths for a whole week continuously (except bedtime) exhausted me, & I longed for a chat with a woman. And it was a fruitless longing. So I say: Where was my co-variation? In Print No. 9 & 10 ‘were not divided’. Then why in festive Brummagem? I never forgive you for that! . . .

He signed the letter “NIMROD-JAEGER”. The name Nimrod is found in the Old Testament, first mentioned in Genesis 10:9 where that renowned giant is described as “a mighty hunter”. The first two words of that description (“a mighty”) match those of the covert Theme’s title (A Mighty Fortress). That three-word phrase parallels another given in Jaeger’s letter that also appears in the Old Testament. The expression “were not divided” is a quotation from 1 Samuel 1:23, the Song of the Bow by King David lamenting the deaths of King Saul and Jonathan at the Battle of Mount Gilboa. As the daughter of an Anglican Rector, Dora was exceedingly familiar with the Bible and would have readily grasped the scriptural origin of Jaeger’s citation. Jaeger’s biblical reference alludes to the opening six bar phrase of the Enigma Theme which is performed exclusively by bowed string instruments. It is conceivable Jaeger subtly hinted at the Biblical catalyst for the covert Theme since David also composed Psalm 46, a chapter known as “Luther’s Psalm” because it inspired the hymn Ein feste Burg. This suspicion is reinforced by Jaeger’s inclusion of the word Ein a few lines before his Biblical quotation.

According to Dora, only Jaeger and Alice were apprised of the secret melody to the Enigma Variations. At one of her first meetings with Jaeger in 1899 at a London rehearsal of the Variations, she “tackled him about the Enigma.” He replied:

Now Dorabella, you must be a good girl and not ask me about that. I do not suppose that I could keep it from you if you were to plead with me, but the dear E.E. did make me promise not to tell you.‘Oh, he did, did he?’ I said slowly, ‘then I will never ask you.’He kissed my hand.‘Forgive my funny little foreign ways, Dorabella dear?’I never mentioned the subject to him again. In those early days I had always hoped I might guess the secret myself, and the recollection of this little scene with Nimrod seems far more momentous to me now than it did at the time.

After the 19 June 1899 London premiere of the Enigma Variations, Jaeger implored Elgar to expand the Finale into a more fully developed movement. In a 27 June 1899 letter, Elgar initially declined Jaeger’s request using language from the Psalms. “I waited until I had thought it out & now decide that the end is good enough for me,” he replied, adding, “You won’t frighten me into writing a logically developed movement where I don’t want one by quoting other people! Selah!” The word “Selah” appears three times in Psalm 46 in verses 2, 7, and 11. Jaeger knew the identity of the covert Theme and would have appreciated this inside joke.

Why Dora?

Dora pestered Elgar with many fruitless attempts at guessing the covert Theme of the Enigma Variations. Elgar egged her on in November 1899 by asking, “Haven’t you guessed it yet? Try again.” She inquired, “Are you quite sure I know it?” He answered, “Quite.” On another occasion she pleaded with Elgar for the answer. He replied, “Oh, I shan’t tell you that, you must find it out for yourself.” “But I’ve thought and racked my brains over and over again,” she insisted. “Well, I’m surprised.” he answered, adding, “I thought that you of all people would guess it.” It is significant that he never cooled her quest for the hidden tune by suggesting there was none to begin with, or that her movement was not even a variation. Why would Elgar tell Dora that she would be the one to guess the correct melodic solution?

There are compelling reasons why Elgar would expect Dora to know the secret melody. As a trained soprano, she participated in performances of sacred choral music, symphonic works with choir, scenes from operas, songs and ballads. Ein feste Burg features prominently in all of those genres by renowned composers of the German school. Elgar was a disciple of the German school. Dieterich Buxtehude produced an organ chorale setting of Ein feste Burg (BuxWV 184). Johann Sebastian Bach cites Luther’s hymn in his chorale cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (BWV 80), his organ prelude by the same title (BWV 720), and set the hymn twice in his Choralgesänge (Choral Hymns) as BWV 302 and BWV 303.

Johann Pachelbel composed an organ Fugue & Fantasia on Ein feste Burg. Georg Frideric Handel cites fragments of Ein feste Burg in his oratorio Solomon (HWV 67). Felix Mendelssohn cites Ein feste Burg in the Finale of the Reformation Symphony (1830) followed by a set of variations. Giacomo Meyerbeer, a cousin of Felix Mendelssohn, quotes Ein feste Burg in his five act grand opera Les Huguenots (1836). Joachim Raff composed the orchestra overture Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott Op. 127 (1855). Richard Wagner cites phrases from Ein feste Burg in Kaisermarch (1871), a work that celebrates Prussia’s victory in the Franco-Prussian War. Carl Reineke wrote the Reformations Ouvertüre mit Variationen über Ein‘ feste Burg Op. 191 (1878). Ein feste Burg is arguably the most quoted melody by the German school. It is cited by composers admired and assiduously studied by Elgar such as Bach, Mendelssohn, and Wagner.

Dora was an active member of the Anglican church, singing in her church choir. Ein feste Burg appears in Anglican hymnals. For instance, it is listed as hymn No. 310 in The Anglican Hymn Book under the title Our God Stands Firm, Our Rock and Tower accompanied by the German subtitle Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. That particular Anglican hymnal was published in London in 1871.

Elgar positioned Dora’s variation immediately after Jaeger’s, the only movement in the Enigma Variations dedicated to a native German Protestant. The tuning of the timpani for Variation IX is indicated as “(in E♭, B♭, F.” Those three note letters present a thinly disguised anagram of “EFB”, the acronym for Ein feste Burg. The first three letters (in E) are anagram of “Ein”, the first word of the covert Theme’s title. Such obvious clues should not have escaped Dora’s notice, particularly as she became very good friends with Jaeger. The nickname “Dorabella” is an unmarried soprano character in Mozart’s comic opera Così fan tutte. The title of Mozart’s opera is three words in a foreign language, a feature shared by the covert Theme.

Dora visited Worcester on 4 May 1899 to attend a concert of the Worcestershire Philharmonic Society directed by Elgar. Following the usual “merry tea-party” after the concert, she visited Elgar’s new residence called Craeg Lea. The sobriquet is an anagram constructed from a reverse spelling of his surname (Craeg Lea) mingled with the initials from the forenames of his daughter (Carice), himself (Edward), and his wife (Alice). Dora recounts that evening visit in her memoir:

That evening E.E. played the whole of the Variations and played the ‘Intermezzo’ again afterwards for me to dance to; but I would have rather sat still and heard him play it, I should not have cared how often; the thrill of it was still upon me. (E.E. said there was only a trace of the ‘Enigma’ theme in the ‘Intermezzo’ which no-one would be likely to find unless he knew where to look for it.)

In brief explanatory notes written in 1927 for the Duo-Art pianola rolls of the Enigma Variations, Elgar clarified where to track down remnants of his Enigma in Variation X. His notes were eventually published by Novello in 1947 under the title My Friends Pictured Within. In his commentary for Variation X, Elgar advises, “The inner sustained phrases at first on the viola and later on the flute should be noted.”

Why would Elgar issue such a quizzical directive? He draws attention to the middle voice of Dorabella without any explanation whatsoever. His use of the word “noted” cleverly suggests taking a closer look at the notes of these inner sustained phrases. Honing in on these inner voices uncovered the initials of Ein feste Burg and two four-note incipits of its ending phrase. The initials are provided in reverse order by the viola solo in bars 366-367 as the letters from the sequential notes “B-F♯-E♯”. The viola soloist crescendos in bar 366 to a mf (mezzo-forte) on the downbeat of bar 367. The dynamic mf deftly furnishes the initials of Mighty Fortress. The reverse encoding of “EFB” in the viola solo line is followed in bar 367 with a rising diminished 5th to B moving in bar 367 by a descending major 2nd to A and a descending minor 6th to C♯. These three additional consecutive note letters “B-A-C” generate a phonetic spelling of back, a word defined by Merriam-Webster as “the rear part” and “a place away from the front”. The Viola Solo “EFB Back” Cipher is positioned in the 16th through 18th measures of Dorabella.

This adjacent decryptions of the covert Theme’s initials followed by the word back suggests looking for the backend of Ein feste Burg in this movement. That is precisely what is found in bars 382-385 and 404-407 of Variation X where the flutes perform an augment version of a four-note incipit (G-F♯-E-D) from the ending phrase of Ein feste Burg. These four-note melodic fragments parallel those observed in Variation XIII where Elgar cites an augmented four-note incipit from a concert overture by Mendelssohn. In his Reformation Symphony, Mendelssohn introduces Ein feste Burg on the solo flute. These inconspicuous yet important features explain why Elgar draws attention to the inner line of Dorabella. After the first augmented fragment of Ein feste Burg played by the flutes, the principal oboe plays B at the end of beat two immediately followed by F and E in the flutes. This presents another backward rendering of “EFB” as was observed earlier in bars 366-367. These note sequence cryptograms are marked by Elgar’s initials (EE) and a short form of his forename (ED). Other cryptograms in the Variations are stamped by his initials or his name.

Out of all of the Enigma Variations, Dorabella most clearly quotes a four-note incipit from the covert Theme. If only Dora listened for fragments of the melody’s ending rather than its beginning, she could have reasonably guessed its identity. The preeminence of the ending over the beginning is acknowledged at the end of the extended Finale by Elgar’s quotation from stanza XIV of Elegiac Verse by Longfellow, “Great is the art of beginning, but greater the art is of ending.”

When Elgar’s wife Alice let slip the rumor they were searching for a house in London, his friends banded together in the Fall of 1897 to establish a choral and orchestral ensemble called the Worcestershire Philharmonic Society. Their objective was to entice Elgar to remain where his musical talents would be publicly celebrated and remunerated. They appointed him artistic director and granted free rein with concert programming. Elgar accepted the appointment and selected the chorus “Wach Auf” from Richard Wagner’s opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg as the signature song for the new Society. In his May 1898 program note, Elgar acknowledges that the text of “Wach Auf” comes from a “Reformation Song” by Hans Sachs. In his 700-line long poem The Wittenberg Nightingale, Sachs likens Martin Luther to a “blissful nightingale” whose song “rings through hill and valley” as the sun rises in the East. The Society’s letterhead faithfully depicts a nightingale singing over hills and valleys at dawn. The nightingale perched over the letter E in “SOCIETY” symbolizes Martin Luther whose most famous Reformation song is Ein feste Burg.

It is highly germane (pun intended) that “Wach Auf” is a poetic and musical homage to the renowned German reformer Martin Luther, the composer of Ein feste Burg. Elgar conducted performances of “Wach Auf” before, during, and after he completed the Enigma Variations. Of all the songs he could have chosen as the Society’s theme song, Elgar selected a Lutheran anthem. Dora regularly attended concerts of the Worcestershire Philharmonic Society and should have grasped the possibility that Elgar chose a Protestant theme as the covert melody of the Enigma Variations. In an interview for The New Republic magazine, Julian Rushton rejects Ein feste Burg as the covert Theme of the Enigma Variations because Elgar’s Roman Catholicism would presumably preclude from consideration a Protestant anthem. When appointed director of the Worcestershire Philharmonic Society, Elgar chose a Lutheran anthem as its theme song. He conducted that paean to Luther at concerts held before, during, and after he birthed the Enigma Variations. As a Vice President of The Elgar Society, will Rushton publicly retract his demonstrably false objection?

Elgar’s fascination with the Book of Psalms is understandable as it is widely considered the most musical book of the Bible. Each chapter is a sacred poem intended to be sung like a hymn, and many are prefaced with instructions for the musicians. Elgar composed two settings of the Psalms. Great is the Lord ( Psalm 48) Op. 67 was written between 1910 and 1912 and premiered at Westminster Abbey in 1912 to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Royal Society. Give Unto The Lord (Psalm 29) Op. 74 was produced for the Festival of the Sons of the Clergy in 1914 and first performed at St. Paul's Cathedral. Both sites are Anglican with public memorials to General Gordon. Westminster Abbey has a memorial bust in the northwest tower chapel. St. Paul’s Cathedral has a memorial bronze tomb. Gordon refers to various passages from the Psalms in his journals from Khartoum. There are also many references to the Psalms in letters to his sister. Gordon’s journals and letters were published and widely read after his tragic death in 1885. It is theorized that Elgar initially planned to cite Ein feste Burg in his Gordon Symphony due to its historic associations with Christianity and the military before abruptly altering course to compose the Enigma Variations.

Dora recounts various episodes in her memoir when she and Elgar conversed about the Psalms. On page 54 she recalls a visit with Elgar at Birchwood Lodge in February 1903:

I found E.E. very busy with the ‘book’ of The Apostles. The study seemed to be full of Bibles. He had a Bible open on the table in front of him and there seemed to be a Bible on every chair and even one on the floor.‘Goodness!’ I said. ‘What a collection of Bibles! What have you got there besides the Authorized and Revised Versions?’‘I don’t know; they’ve been lent to me. I say, d’you know that the Bible is a most wonderfully interesting book?’‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I know it is.’‘What do you know about it? Oh, I forgot, you do know something about it. Anyway, I’ve been reading a lot of it lately and have been quite absorbed.’He appeared to be looking out texts and I offered to help.‘I want something that will fit in here’ — pointing to a line.I thought for a moment and fortunately something suitable occurred to me and I quoted it.‘You don’t mean to tell me that comes in the Bible? Show it to me.’I found the 85th Psalm in one of the Bibles and laid it before him.‘Well! That’s extraordinary! It’s just what I want here.’

The passage that Dora recited is Psalm 85:10, “Mercy and truth are met together, righteousness and peace have kissed each other.” Elgar cites this text in the second scene of The Apostles called “By the Wayside.” On pages 93-94 of her memoir, Dora describes a visit to Plȃs Gwyn when she assisted Elgar with sorting through his mail. This sparked a conversation about another Psalm:

The following day I heard more of The Kingdom music. E.E. worked alone all the afternoon, and after tea I helped him with sorting papers in the study.We heard the postman come and I went to see if there were letters for either of us. The Lady was in the hall.‘One for you, dear Dora, and some dull things for H.E. [His Excellency] Will you take them in’‘What’s all this rubbish? I can’t be bothered with it.’‘Shall I see what they are?’Most of it was easily disposed of, but I stared at the last one in silence.‘It’s from a Temperance Society.’ I said, ‘They want you to join, and the Secretary encloses a card for the coming season.’ Hardly able to speak for sheer joy I put the card down in front of him, adding, ‘They’ve chosen a good motto for their Society, haven’t they?’ Printed in old English lettering at the top of the card was, ‘Hold Thou me up and I shall be safe.’‘That’s from the Psalms, isn’t it?’‘Yes,’ I said, ‘the hundred and nineteenth.’‘Could you believe it?’ he began ⸻ and then I’m afraid we simply exploded with laughter!I have never known him more delighted with anything.

One reason for the levity is that as an observant Roman Catholic, Elgar routinely drank wine as part of the Eucharist. The quotation is from Psalm 119:117, “Hold thou me up, and I shall be safe: and I will have respect unto thy statutes continually.”

Dora makes a final reference to the Psalms on page 163 of her memoir when describing how Elgar carefully selected passages from the Bible to construct the libretto of The Apostles:

With great skill he chose the ‘text’ of ‘The Apostles’ with a view to showing how the sayings of Christ struck the Disciples at he first hearing, and he does so, not only in the language of the Holy Scripture but in quotations from many parts of the Bible, parts that would be known to the Apostles: the Law, the Prophets and the Psalms of David. So cleverly is it done that they sound as if really consecutive.The effect of this treatment is the revealing of character, and, as we go on, we recognize each Apostle and Disciple as a separate personality. Thus Elgar says something new to us on the subject of the Gospel story.

In the Prologue of that oratorio, Elgar cites Psalm 2:1-2. In the first scene, the choir sings Psalm 8:4-6 in “The Calling of the Apostles.” Elgar quotes Psalm 68:18 in “The Ascension”, the final scene of Part II. In that uplifting scene, he also cites Psalm 24:7-10. Concerning the libretto of The Apostles, Elgar advised in his 1905 biography, “I have been thinking it out since boyhood, and have been selecting the words for years, many years.” The Psalms were clearly a subject of interest from his youth and remained so well into his professional career as composer. There are undoubtedly other conversations between Elgar and Dora about the Psalms that never made it into her memoir. Dora’s intimate knowledge of the Psalms made her an ideal candidate to guess the covert Theme of the Enigma Variations. The title of Ein feste Burg comes from the first line of Psalm 46, a chapter dubbed “Luther’s Psalm” by Thomas Carlyle.

Elgar hyphenated the last two initials in the title of Variation II (H.D.S-P.), a movement dedicated to his friend Hew David Stuart Powell. This is the only movement with a hyphen in its title. The hyphen is anomalous as Powell’s Oxford University records dating from 1878 lack one in his name. Elgar added the hyphen between S and P to hint at the scriptural inspiration for the covert Theme. The letters “SP” are a reverse spelling of “Ps.”, the standard abbreviation of Psalm. In their original Hebrew, the Psalms employ a high hyphen called a maqaf. The D before the “S-P” is the initial for David, the chief author of the Psalms. Dora knew the initial D stood for David, but failed to connect that overt reference to the covert allusion to the Psalms by the out-of-place dash between the S and P.

Dora recounts in her memoir an interesting exchange with Elgar about a particular hymn in the standard reference Hymns Ancient and Modern.

We were going through the proofs of the Coronation Ode and he came to ‘Daughter of Ancient Kings’. I felt as if turned to stone and I know I went white.‘How do you like that? ⸺ What’s the matter?’I said I thought it was charming, but I knew the beginning quite well.‘What do you mean?’‘It begins like a hymn in the Ancient and Modern book.’‘What hymn? I don’t know anything about your hymns. Can you play it.’So I stretched across him and played the first line of 528. ‘The likeness only goes so far,’ I said.‘Well, I can’t help it. I’ve never heard that wretched hymn in my life.’‘I am quite sure you haven’t,’ I said, ‘It’s only a coincidence.’

Elgar was being disingenuous with Dora about his presumed unfamiliarity with Protestant music. In an interview with The Strand Magazine published in May 1904, Elgar confessed attending as many Anglican services as possible:

I attended as many of the Cathedral services as I could to hear the anthem, and to get to what they were, so as to become thoroughly acquainted with the English Church style. The putting of the fine new organ into the Cathedral at Worcester was a great event, and brought many organists to play there at various times. I went to hear them all. The services at the Cathedral were over later on Sunday than those at the Catholic Church, and as soon as the voluntary was finished at the Church I used to rush over to the Cathedral to hear the concluding voluntary.

Although Elgar may have been unfamiliar with hymn no. 528, he certainly heard and performed the Protestant anthem Ein feste Burg on numerous occasions. At the 1885 Three Choirs Festival in Hereford, Elgar served on the third desk of the first violins in a performance of Bach’s cantata Ein feste Burg (A Stronghold Sure). That same cantata was reprised at the 1890 Three Choirs Festival in Worcestershire. Elgar faithfully London concerts led by Hans Richter where he heard Wagner’s Kaisermarsch, an orchestral work that cites Ein feste Burg. Elgar was interested in marches as reflected by his five completed Pomp and Circumstance Marches for orchestra and sketched a sixth that was elaborated by Anthony Payne in 2005-2006. Between 1879 and 1897, Richter included Kaisermarsch no less than fifteen times. The dates of those performances are listed below:

- May 7, 1877

- May 28, 1877

- May 5, 1879

- May 3, 1882

- July 2, 1883

- April 21, 1884

- October 24, 1885

- October 23, 1886

- May 7, 1888

- June 24, 1889

- July 14, 1890

- July 20, 1891

- May 30, 1892

- May 20, 1895

- May 31, 1897

As a Richter devotee, Elgar undoubtedly attended many of those performances. Elgar’s distinctive handling of the Mendelssohn fragments in Variation XIII presents some striking parallels with Wagner’s treatment of Ein feste Burg in Kaisermarsch. Richter’s towering influence assured that the Kaisermarsch would be programmed by other orchestras throughout England during that period. The August 1, 1889 issue of The Monthly Musical Record contains a glowing review of a June 24 Richter Concert in London that was capped off by the Kaisermarsch:

The “Kaisermarsch” — that grand page of brilliant orchestral writing to celebrate a grand page in German history — again produced its overpowering effect at the conclusion of one of the finest concerts of the season.

That commentary also mentions the premiere of Hubert Parry’s Symphony No. 4 in E minor dedicated to Hans Richter. It describes “the diffuse finale” of that work with “its marked reminisces from . . . ‘Kaisermarsch’ . . .” Elgar attended that premiere after only recently settling in Kensington with his wife following their marriage in May 1889. Elgar gleaned insight and knowledge from Parry’s contributions to Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, performed his music as a sectional violinist, and publicly acknowledged Parry as “the head of our art in this country.” As evidence of his respect towards Parry, Elgar orchestrated his popular hymn Jerusalem which is now a centerpiece at the Last Night of the Proms.

Dora surmised that “when the solution [to the Enigma] has been found, there will be no room for any doubt that it is the right one.” As the recipient of the Dorabella cipher, she was fully aware of Elgar’s fascination for secret codes. Without any training or interest in cryptography, she lacked the skills necessary to detect and decode ciphers embedded within the Enigma Variations. As a Protestant with an excellent music education, Dora was intimately familiar with Luther’s Ein feste Burg. She knew enough to guess the correct tune, but not enough to authenticate it by solving Elgar’s cryptograms. No wonder Elgar advised in the original 1899 program note, “The Enigma I will not explain – its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed.” A decryption cannot be guessed. To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

%20Bars%20363-370%20%E2%80%9CEFB%20Back%E2%80%9D%20Viola%20Solo%20Notes%20CiphersCiphers.png)

%20Bars%20381-386%20Ein%20Feste%20Burg%20Phrase%20B%20Incipit.png)

%20Bars%20404-407%20Ein%20Feste%20Burg%20Phrase%20B%20Incipit.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please post your comments.