My Father, Lord of heaven and earth, I am grateful that you hid all this from wise and educated people and showed it to ordinary people. Yes, Father, that is what pleased you.

Jesus praying in Mathew 11:25-26

The German composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) exerted a profound and lasting impact on the English composer Edward Elgar (1857-1934). So undeniable is this fact that Barry Millington, the Editor of The Wagner Journal, writes that Wagner’s “. . . influence on the harmonic language of composers such as Parry, Stanford and Elgar is self-evident.” From 1877 through 1902, Elgar attentively studied Wagner’s orchestration, innovative harmonic language, and system of Leitmotifs. During these 25 years, Elgar regularly heard Wagner’s music in London at concerts conducted by Hans Richter and August Manns. He also made numerous trips to Germany to bask in the mythical romanticism of Wagner’s operas. These protracted efforts culminated in 1900 with The Dream of Gerontius, a numinous homage to Wagner’s final opera Parsifal.

Wagner's influence on Elgar's music is a fertile field of research and scholarship. In his groundbreaking 1985 paper Elgar and Wagner, Peter Dennison unmasks and documents Leitmotifs from Wagner’s operas in Elgar’s early choral works. Dennison reasons that a careful study of Wagner's music permeated Elgar’s compositions. Consistent with this pattern, Elgar adapted Wagnerian Leitmotifs in Chanson de Nuit, a solo violin piece with piano accompaniment composed in 1889-90. In 2008, Laura Meadows picked up where Dennison left off in her exhaustive thesis Elgar as Post-Wagnerian: A Study of Elgar’s Assimilation of Wagner’s Music and Methodology. Meadows lays out a compelling case that Elgar was “profoundly influenced by Wagner from an early age and this influence gradually infiltrated his compositional thoughts.” She traces this process through Elgar’s large-scale choral and orchestral compositions through 1899.

Ian Beresford Gleaves ventures further down this path in his article Elgar and Wagner published in the July 2007 issue of The Elgar Society Journal. He observes that Wagner’s enduring impact on Elgar extended to his orchestration of the Enigma Variations which “assimilates many of Wagner’s methods, particularly as regards the tutti.” He also draws attention to a Wagnerian modulation in bars 30-31 of Variation I that recalls bars 16-17 of the Prelude to Act I of Tristan. Although not recognized until now, Elgar further emulates Wagner’s methods in his treatment of the melodic quotations from Mendelssohn’s overture Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt (Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage) in Variation XIII. Only one work by Wagner incorporates melodic fragments by another composer—the Kaisermarsch (Imperial March) composed in 1871.

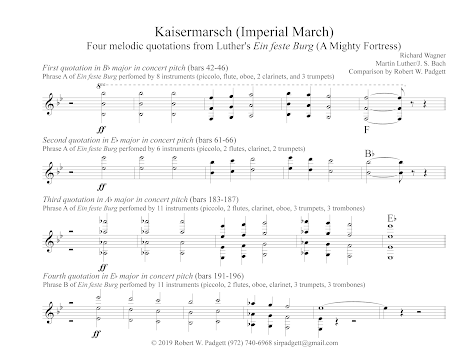

There are some extraordinary parallels between Wagner's quotations of Martin Luther's hymn Ein feste Burg (A Mighty Fortress) in the Kaisermarsch and Elgar's Mendelssohn quotations in Variation XIII. The impetus for comparing these two sets of melodic quotations emerged from two factors. As previously outlined, the first is that Elgar was deeply influenced by an intensive study of Wagner’s music from 1876 through 1902. The second is that the covert Theme to the Enigma Variations is Ein feste Burg, the renowned battle hymn of the Protestant Reformation composed by a heretic excommunicated by Pope Leo X. This melodic solution readily explains why Elgar, a practicing Roman Catholic, adamantly refused to disclose the melodic lynchpin to his Enigma Variations.

The first and most obvious parallel to emerge between the melodic quotations in Kaisermarch and Variation XIII is they originate from alien works with original Geman titles by other German composers. Wagner cites Ein feste Burg by Martin Luther, and Elgar quotes Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt by Felix Mendelssohn. Far from being remote from one another, Luther and Mendelssohn are linked by a variety of factors. Mendelssohn was baptized a Lutheran on the anniversary of Bach’s birth. Luther’s Ein feste Burg is quoted by Mendelssohn in the fourth movement of the Reformation Symphony. They spoke German, contributed to the establishment of the German School, and espoused the importance of sharing the gospel message through hymns and other sacred music.

A second conspicuous parallel concerns the number of melodic quotations in Kaisermarsch and Variation XIII. There are four citations of Ein feste Burg in Kaismarch, and four from Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage in Variation XIII. A third parallel is that Wagner’s and Elgar’s four melodic fragments are framed in three contrasting keys. Wagner selected the major modes of B-flat, E-flat, and A-flat. Elgar chose A-flat and E-flat major, matching two of Wagner’s three key choices. His divergent key choice of F minor is associated with Wagner’s B-flat major quotation as that phrase cadences in the parallel key of F major.

A fourth parallel centers on the distribution of the melodic fragments. Three of Wagner’s quotations are of the opening phrase of Ein feste Burg (Phrase A), and the fourth of its ending phrase (Phrase B). Although Elgar’s citations are of the same melodic fragment, they reflect a similar distribution because three fragments are in a major mode and one is in a minor key. Wagner’s fourth and final fragment from Ein feste Burg is in E-flat major. This presents a fifth parallel as Elgar’s fourth and final Mendelssohn quotation is also in that identical key.

A sixth parallel is the number of notes in Wagner’s quotations corresponds to those in Elgar’s clarinet solos that introduce the Mendelssohn quotations. There are ten notes in Wagner’s quotation of Phrase A from Ein feste Burg. There are four notes in Elgar's Mendelssohn quotations in A flat major, and this phrase is further elaborated by six more notes to form a coherent clarinet solo comprised of ten notes. There are nine notes in Wagner's quotation of Phrase B from Ein feste Burg. Elgar's Mendelssohn fragment in F minor has four notes that are extended with the addition of five more notes to form a complete nine-note soli. A seventh parallel is based on how Wagner and Elgar orchestrated their quotations. The F minor Mendelssohn fragment is performed in octaves by the trumpets and trombones. This same orchestration technique is deployed by Wagner for his Ein feste Burg quotations with the melodic line dominated by the trumpets and trombones at the octave.

An eight parallel is the concluding notes of each set of melodic quotations encode the initials of an important three-word phrase in the German language. The final notes of Wagner’s melodic fragments of Ein feste Burg in order of appearance are F, B-flat, and E-flat. Those three note letters are an anagram of the initials for Ein feste Burg. The last notes of the Mendelssohn fragments in Variation XIII are A-flat, F, and E-flat. Those three letters are an anagram of violinist Joseph Joachim’s personal romantic motto “Frei aber einsam” (Free but lonely). Those initials served as the foundational motif for the F-A-E Violin Sonata composed in honor of Joachim by Robert Schumann, Albert Dietrich, and Johannes Brahms. Through the key letters of the Mendelssohn fragments, Elgar enciphered a well-known music cryptogram used by famous German composers.

As a young protégé of Mendelssohn, Joachim performed Beethoven’s violin concerto at a Royal Philharmonic Society concert in London on May 27, 1844. At only twelve years of age, Joachim was granted a special exemption from a rule barring child prodigies. Joachim was a perennial favorite of Queen Victoria and the British public. It is entirely fitting that his romantic motto is encoded by the keys of melodic fragments composed by his champion, Felix Mendelssohn. Like Joachim’s motto, the title of the covert Theme to the Enigma Variations is three words in German.

There is another intriguing cryptographic link between Wagner's and Elgar’s melodic quotations because both sets encode the initials for Ein Feste Burg. In Wagner's Kaisermarsch, the three Phrase A quotations of Ein feste Burg are presented in three contrasting keys: B-flat major (bars 42-46), E-flat major (bars 61-66), and A-flat major (bars 183-187). Each Phrase A quotation concludes with a half cadence a fifth above the starting key. The B-flat major fragment cadences in F major; the E-flat major fragment cadences in B-flat major; the A-flat major fragment cadences in E-flat major. The key letters of those three half cadences (F, B-flat, and E-flat) are an anagram of the initials for Ein feste Burg. These fragments are drawn from Bach's version in the final movement of his sacred cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80. Wagner revered Bach, a Lutheran composer who encoded words in his music.

Elgar enciphers the same three initials alluded to by the enigmatic title of three asterisks (* * *) by his handling of the Mendelssohn fragments. The key to this code is rather simple. The number of statements of a fragment in a given key designates the corresponding scale degree of that key as the solution letter. Two fragments in A-flat major implicate the second scale degree of that mode (B-flat). One fragment is in F minor pinpoints the first scale degree of that key ( F). There is also one final quotation in E-flat major that designates the first scale degree of that mode (E-flat). Those three note letters are the absent initials indicated by the three mysterious asterisks in the title of Variation XIII. It is remarkable that the first letters in the titles of the movements immediately before (XII B. G. N.) and after (XIV E. D. U. & Finale) Variation XIII also provide those same initials. Elgar wrote those three letters as FEb on the Master Score, twice on the covert, and again on the final page. He also provided those three letters in the form of an acrostic anagram at the conclusion of the extended Finale completed in July 1899.

There is yet another tantalizing link between Wagner’s Kaisermarsch and the Mendelssohn fragments cited in Variation XIII. The accompaniment to the Mendelssohn fragments consists of a pulsating ostinato derived from the Enigma Theme’s palindromic rhythm of alternating pairs of eighth notes and quarter notes. In Morse Code (a system Elgar knew well), this palindromic ostinato spells out the letters “MI” followed by “IM”. These two sets of initials match those for the French (Marche Impériale) and English (Imperial March) translations of the original German title. Elgar encoded within the accompaniment figure the French and English initials of a work by Wagner that quotes the covert Theme in a manner eerily similar to Elgar’s handling of the Mendelssohn fragments.

There are some interesting points of correspondence between the Enigma Theme and Kaisermarsch. Both are set in common time (4/4) and have two flats in the key signature with Kaisermarsch in B-flat major, and the Enigma Theme in the relative key of G minor. Wagner employs the G minor chord as the harmony for the first note of the opening Ein feste Burg quotation in bar 42. There are other similarities between the Kaisermarsch and the Enigma Variations. For instance, a series of descending melodic fourths beginning at 234 of the Kaisermarsch are virtually identical to the falling melodic fourths at the outset of Variation XIII that is repeated several times throughout the movement.

Wagner’s Kaisermarsch was exceedingly popular from 1877 through 1911 before the conflagration of World War I rendered all things German strictly verboten. On May 7, 1877, Wagner conducted Kaisermarsch at a rehearsal in the Royal Albert Hall. Hubert Parry attended the event and recorded this reaction in his diary:

All the morning at the rehearsal at the Albert Hall. Wagner conducting is quite marvellous; he seems to transform all he touches, he knows precisely what he wants and does it to a certainty. The Kaisermarsch became quite new under his influence and supremely magnificent. I was so wild with excitement after it that I did not recover all the afternoon. The concert in the evening was very successful and the Meister was received with prolonged applause but many people found the Rheingold selection too hard for them.

Elgar heard numerous performances of Wagner’s Kaisermarsch in the years leading up to the genesis of the Enigma Variations. As documented in Christopher Fifield’s thoroughly researched and endlessly fascinating biography, Hans Richter conducted no less than fifteen performances of Kaisermarch at Richter Concerts in London between 1879 and 1897. The dates of those performances are listed below:

- May 7, 1877

- May 28, 1877

- May 5, 1879

- May 3, 1882

- June 2, 1883

- April 21, 1884

- October 24, 1885

- October 23, 1886

- May 7, 1888

- June 24, 1889

- July 14, 1890

- July 20, 1891

- May 30, 1892

- May 20, 1895

- May 31, 1897

Elgar likely attended most if not all of these performances in his quest to hear Wagner’s music. Richter’s towering influence assured that the Kaisermarsch would be programmed by other orchestras throughout England during that era. The August 1, 1889 issue of The Monthly Musical Record contains a glowing review of a June 24 Richter Concert in London that was capped off by the Kaisermarsch:

The “Kaisermarsch” — that grand page of brilliant orchestral writing to celebrate a grand page in German history — again produced its overpowering effect at the conclusion of one of the finest concerts of the season.

That article also mentions the premiere of Hubert Parry’s Symphony No. 4 in E minor dedicated to Hans Richter. It describes “the diffuse finale” of that work with “its marked reminisces from . . . ‘Kaisermarsch’ . . .” Elgar attended that premiere after only recently settling in Kensington with his wife following their marriage in May 1889. Elgar gleaned insight and knowledge from Parry’s contributions to Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, performed his music as a sectional violinist, and publicly acknowledged Parry as “the head of our art in this country.” As evidence of his respect towards Parry, Elgar orchestrated his Jerusalem which is now a mainstay at the Last Night of the Proms.

Elgar’s handling of the Mendelssohn fragments in Variation XIII proves to be a stealth homage to Wagner’s treatment of Ein feste Burg in the Kaisermarsch. This analysis identified nine parallels between these two sets of melodic quotations, a sum too high to be ascribed to chance. The cryptographic links are the most intriguing as both series of quotations encode the initials for Ein feste Burg. It may be confidently argued that Elgar’s emulation of Wagner in his handling of the Mendelssohn fragments implicates Ein feste Burg as the covert Theme to the Enigma Variations. The overwhelming evidence for this discovery is contrapuntal, cryptographic, and multivalent as it accounts for a range of anomalies such as the conspicuous insertion of the Mendelssohn quotations. To learn more about the secrets of the Enigma Variations, read my free eBook Elgar’s Enigmas Exposed. Please help support and expand my original research by becoming a sponsor on Patreon.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please post your comments.